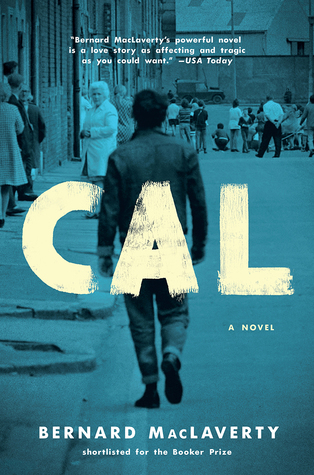

Fine, fine novel about the Troubles in the mid 60's. The blurbs call it a classic, the "Passage To India" of the era and though I don't unfortunately know the Forester book very well, it's easy to see why.

Cal McClusky is a teenager on the dole, the only son of an abbatoir man who is in the midst of some serious turmoil- physical (puberty), political (he's the only son of a widowed father who is stubbornly staying in a hostile Ulster neighborhood, a bitter Roman Catholic among aggressive Protestants), emotional (guilt over the passive, ambivalent assistance he gave to some IRA school friends in a couple of their, um, "assignments") and romantic (he's got a straining, largely voyeuristic crush on the widowed wife of the man who was killed).

It's easy to relate to Cal, at least for this reader. He's awkward, gangly, self-hating, confused, and unsure of himself and his place in the world. Hell, in some much tamer ways I WAS Cal back in my teenage years- sufficiently scared and uncomprehending of the world outside to brood in anguish in my room all day every day, scurrying to and from the library to take out records, awkwardly strumming along with my Nirvana cds and endlessly pushing my greasy hair back over my eyes.

Cal's 'courtship' of the widow Marcella is written sensitively and with some drizzlings of humor. He can't talk to her for obvious reasons and he can pretty much only worry and peek and semi-stalk and fantasize. Meanwhile, his house is being firebomb threatened and his gruff, repressed father has taken to unearthing the gun from the floorboards of his bedroom and sleeping with it. Its both protection and incrimination- if the cops find it for whatever reason, he's done for. If he uses it he's done for, for that matter.

I won't give away any spoilers but suffice to say the background is set for the plot to start moving. I am not the greatest at forecasting plot twists, but with this setup it's very suggestible what might happen next. We get answers to a lot of our immediate questions, but it's a tribute to MacLaverty's art that even when things are revealed there are still surprises and things withheld in very meaningful ways.

Why does brother kill brother?

I do hope that Cal was read widely when it was written (I do think it was) and contributed in some small way to abating the fear, terror (literal and figurative), and disgust still thick as smoke in the air when it was first published. Pascal was famous for saying that all of mankind's problems can really be traced back to our inability to sit quietly in our rooms. True indeed, but we must also be careful what sitting quietly might summon, the dark side of solitude, as it were.

***

Here is a small paper I wrote about it:

The Shell of Self: Identity, Choice and Redemption in Cal

The final sentence of Bernard Mac Laverty’s novel Cal is as enigmatic and yet profoundly suggestive as any successful ending would wish to be. Upon first reading, its specificity and bitter irony seems both matter-of-fact and also somewhat ambiguous: “The next morning, Christmas Eve, almost as if he expected it, the police arrived to arrest him and he stood in a dead man’s Y-fronts listening to the charge, grateful that at last someone was going to beat him to within an inch of his life.” (154) The bitter irony in the last dozen words is what complicates matters considerably.

Why is Cal “grateful” that someone will beat him up, to within an inch of his life, at that? It could be read as sarcastic fatalism: poor Cal is yet again going to be at the mercy of powers which have defined and dominated his life thus far and this arrest will be no more than a further humiliation among many others. It could be read as a final, pathetic defeat, suggesting that Cal is about to surrender totally, fatally, to this oppression to get rid of his misery and to stop struggling once and for all. Neither of these answers seem sufficient, and for good reason. It is not hard to sympathize with Cal throughout the narrative and this seems to be MacLaverty‘s intention. Elimination at the hands of his tormenters is not what he deserves. It might be difficult to stomach, but Cal might be on his way to redemption.

Cal has his faults but those very faults are entwined with his virtues and all-too-human characteristics. He is guilt-ridden to the point of stagnation, self-hating and constantly self-critical, most importantly he is not prone to acts of self- assertion or self-defense against the hostile world which he properly rejects. Cal tends to retreat or to isolate himself, either in his room at his father’s house or, later when that space is no longer available, in the cabin outside Marcella’s. At the risk of falling into the reductive, ingratiating language of the self-help industry, he certainly has ‘low self esteem’ and could indeed try to be a ‘better person‘. All of this is, at least arguably, true of Cal. It is also important to remember, in contrast, that he is guilt-ridden and self-hating because of his conscience, not because he lacks one. Cal is in many ways an ordinary adolescent but what is plaguing him is far more immediate and dreadful than puberty alone.

It is widely accepted that adolescence is, at least in part, about questioning one’s own identity. This is a cliché, of course, but it also points toward a more complex and textually relevant issue. One way to explore one’s identity is through culture, engagement with culture, as a sort of psychic anchor. Part of being interested in the arts is the discovery of what one loves or hates, what one is passionate about, what one believes, what makes one truly happy. Exploring culture- be it music or literature or film- is a way to not only develop talents but also to begin a process of self-discovery. Taste, particularly for young people, can be a gesture towards self-understanding, a piece of the puzzle of one’s identity.

Amid his alienation, Cal seems to find solace in music. Early on we see him sitting in his room, awkwardly strumming his guitar, listening to his Rolling Stones# LP “to drown the silence…Within the tent of his hair with eyes shut he listened to the sounds his fingernails picked from the strings as he sang in an American voice the things he’d heard on record.” (10, italics mine) Cal is not only trying to keep his mind off the tension he feels, he’s also exploring a different form of self-expression, a possibility of a different identity, separate from the ‘crotte de vache’ (in his own self-loathing, angst-ridden terms) which disgusts him so much.

This is significant because Cal is a character for whom social identity- religious, geographic, and economic- is very much at the heart of what is causing him so much pain and confusion. It is interesting to notice that a short while later, he is flipping through Time magazine and he feels “strangely proud that the place where he lived was given so much room in such an important magazine.” (12) Cal’s social circumstances are alternately overwhelming and underwhelming. He is frightened for his safety as a Roman Catholic in a hostile, threatening Protestant Ulster, which is probably the reason his hometown appears in a worldly magazine in the first place. He is also bored out of his mind. He has chosen not to work in the reeking abattoir with his father, which is reasonable enough, though life on the dole doesn’t seem to offer anything more than a form of economic limbo. It seems that having his hometown spotlighted in Time magazine because of civil strife and pervading despair is an irony which wouldn’t be lost on him.

In contrast to the pugilistic Crilly, killing and robbing does not seem to Cal like a good time at all, or even a possible escape route. It is interesting to note that early in the narrative, when the reader is introduced to the sadistic Crilly and the murderous, pseudo- intellectual Skeffington, Cal’s alienation and longing for change is described through music: “The wailing guitar sequence from ‘The Dark Side of the Moon’ came into his head and he listened to it, moving his fingers.” (23) After his house is burned by Protestant terrorists he specifically returns to his room to reclaim his guitar and finds it ruined, in cinders. When he makes his trips to the library he borrows tapes, not books.

Enter Marcella. Cal’s interest in Marcella isn’t only erotic, though this is certainly an important element for the apparently virginal young man. It’s also existential- a chance to take his life in another direction, a manifestation of possibility. Marcella represents to Cal not only a difference of gender (being an adult female), culture (an Italian emigrant to Ireland) and his past (her husband was, after all, the victim of the drive-by shooting in which Cal did the driving but not the shooting) but also of his future.

His interest in Marcella is described in voyeuristic terms from its beginning to its eventual consummation. He peeks at her through the library stacks, watches from across the street to see when she will leave the library and even gazes at her through her shower window when he is living in her family’s barn. Cal’s voyeurism is connected not only to his adolescent male fascination with the female body but also with the internal guilt and fear which paralyze him. Throughout much of the narrative he looks at Marcella but can hardly bear to touch her. When he manages to do so, in church of all places, it is furtive, ephemeral, a physical version of a glance. The reason for this aspect of Cal’s paralysis is not merely adolescent timidity- Marcella is the obscure object of his desire because she simultaneously represents both his guilt and his possibility for redemption. It’s understandable that Cal would feel both attracted and repelled to her.

Once they finally become lovers and begin to have a steady relationship, he is still burning with the guilt he understandably feels. He can’t tell her the awful secret he keeps, though he must tell her if she is to truly know him, and to love him. It is significant that Marcella describes her previous marriage as a gradual process of indifference. Her husband became a stranger to her over time, their marriage gone distant, not what one would consider a love of any real intimacy. Cal, for his part, cannot truly be her lover until he purges himself of the secret which has imprisoned him in guilt all along. St Theresa once suggested that hell is “the impossibility of love“, and Cal might well understand the meaning of this: “The rest of his prayers consisted of telling himself how vile he was. If he was sick of himself, how would God react to him?” (37) If Cal feels that way about an ostensibly loving God, how is he going to explain to the woman he loves his implication in her husband’s death?

For Christmas, Cal buys her a book of paintings by the German artist Grunewald which significantly contains a painting of a gaunt, suffering Christ on the cross. The image of the suffering Christ is appropriate for Cal in the sense that he is crucified by his social environment- his inherited Roman Catholicism is the root cause of his alienation and the threats within his social context. He doesn’t seem especially pious or devout; on the contrary, his chance of redemption is in love, not faith. Cal won’t be ‘saved‘, in religious terms, but be might be redeemed in secular, emotional ones: “Cal looked at the flesh of Christ spotted and torn, bubonic almost, and then behind it at the smoothness of Marcella’s body and it became a permanent picture in his mind.” (153) Cal’s consideration of the two bodies- one hideous and suffering, the other lovely and peaceful- suggests the difference between Cal’s past and future. It offers the possibility of a recovery, an alternative to the solitude and self-hate which previously defined him.

In his essay “The Geography of Irish Fiction”, John Wilson Foster asserts that one of the recurring themes of the Irish novel is “the attempt to escape…‘the cave of the self.‘ Even when the self appears to have emerged from its cave, it still inhabits what O’Faolain calls ‘the shell of self’, which for my purposes I will take to mean place transformed into memory of place and therefore transportable.“

This insight was originally applied to Gyppo Nolan, though it can also apply equally to Cal Mc Cluskey. Cal needs to escape the social shell imprisoning him. His otherwise repressed and distant father is still too traumatized from the attack to do much but stare out the window. Crilly and Skeffington have nothing to offer him but more anguish and violence and he has suffered enough by associating with them already. He knows, as he has always known, that he must do something conclusive to sever ties with them once and for all. It seems that the reciprocal affection which he finds in Marcella emboldens him, empowers him, it gives him something for which to live.

Shortly after his consummation with Marcella, Cal seems a bit more joyful: ”He walked back to the cottage, his feet splayed like Charlie Chaplin…his excitement was such that he could not sleep.” (142) The next day he sees the ridiculous, bombastic Preacher on the corner of the road, spouting his usual fire and brimstone, and responds with wit and a healthy dignity: “He wind milled his arms and shouted as Cal passed him. ‘Without the shedding of blood there can be no forgiveness.’ ‘Good evening,’ said Cal.” (143) Before Marcella, this eerily relevant statement might have caused Cal to tighten his fists and curse himself some more. Now, he shrugs it off. Instead of letting his social environment dictate his reaction through tormenting him, he is beginning to fortify himself from letting it penetrate. The more he has to be excited about, the more he has to live for and the more he can become stronger within himself.

When he discovers that Crilly has planted a bomb in the very library where Marcella works, he has had enough. The fact that he will inform on them, rather than simply tell them he won’t be a part of it anymore, is as much a line drawn in the sand as his relationship with Marcella. The fact that he goes to Marcella’s after having made the phone call is significant- she’s his source of comfort as much as strength. As they embrace, Cal’s problem is made clear: “He wanted to tell her that he had saved her precious library but knew it would be too complicated. He wanted to be open and honest with her and tell her everything. To explain how the events of his life were never what he wanted, how he seemed unable to influence what was going on around him.” (152) This is precisely why he’s been so troubled throughout the story and why he is about to stop his cycle of paralysis and self-hatred.

Cal‘s decision is irrevocable. It is also freely made of Cal‘s own volition, not the rushed coercion which Crilly pushed on him by making his house a safe house, and therefore a target. By consciously acting, by making an irrevocable decision, he has begun to define on whose terms he will live and define himself. The bitter irony in the concluding paragraph is the irony which attaches to a social context which does not make for easy answers or greeting-card endings.

Before he is arrested, Cal is planning to reveal his secret once and for all, considering writing it down “that way he could say what he meant and not get confused.” (153) The problem is, of course, that this would be evidence which would be used against him, a terrible fact of life in a social matrix in which it seems everyone is implicated, another layer in the ‘shell’ of the self. Cal seems to decide that he will finally relinquish his guilt about his crime, behind prison bars, in necessary: “if he was ever caught…he would write to her and try to tell it as it was.” (153)

At last, Cal will have the chance to release himself from the guilt which has defined him thus far and impeded his development as a person. The arrest, and the beating which follows, is an imprisonment but also, ironically, a liberation. It will serve as a purgation, a hand he forced on himself, the cathartic act through which the guilt and pain he feels will be beaten out of him at last. Cal has spent much of the narrative in a very specific pain and lacking both the reason and the will to overcome it, to “force the moment to its crisis“, in T.S. Eliot‘s phrase. There is also an irony in the fact that though he will have his catharsis through others, the situation has come to a head by his own hand. Cal doesn’t know if Marcella is going to receive him back into her life after his arrest, and this is part of the ending‘s power. The fact is, however, Cal has gone from unwilling participant to conscious agent, makes all the difference in the world. He could not stay in the place he began, and it is now impossible to return to it- he can only go elsewhere. He can only leave the shell. The reader can only hope he isn’t alone when he does.