Every now and then I might get macho about reading a really BIG book. But that's not why I started this one, I swear it. I just wanted to read any book at all by Vollmann, because I kept coming across his prose in magazines or excerpts or whatever, and it's always golden to me. I could have chosen a thinner book -- for instance, every other book by him is thinner -- but I also have a passing interest in the fucked-up ecosystem/economy/history of the Salton Sea region, which lies within this book's target area of Imperial County. Though really this book is focused slightly farther south, on Mexicali and Calexico and Holtville and El Centro and all of the other tiny rural spots that have blossomed, sparkled and faded over the last hundred years of westward expansion into this inhospitably hot, border-bisected desert region that Vollman calls "Imperial". Also, the stretch of history the book encompasses is long enough that the accidental birth and agonizing slow death of the Salton Sea are just blips. But to know that, I had to read the whole thing. Oops.

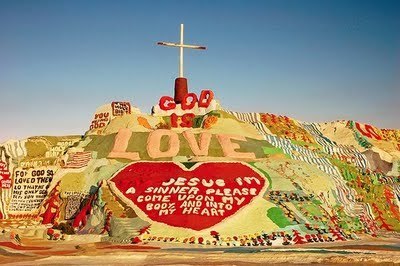

But it's such a handsome hardback. It feels good in the hands. Reading it, I got to luxuriate in all the great features of real-live-paper-books: sprawling two-page map spreads, changes in typeface to indicate the voices of long-expired newspaper advertisements, plenty footnotes and tables and photos and fonts -- none of it gratuitous, either. Bill Vollmann pulled out every trick to enliven this project: describing this region from every angle he can reach, indulging his fascination with it, and trying to make the resulting tome seem organized, cogent and vibrant instead of just a sprawling, repetitive 1300-page mess.

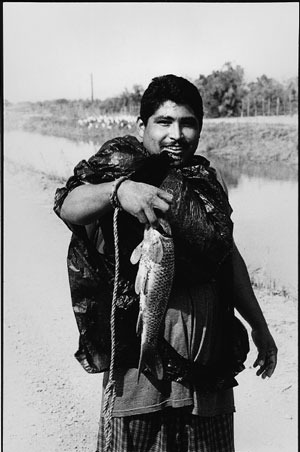

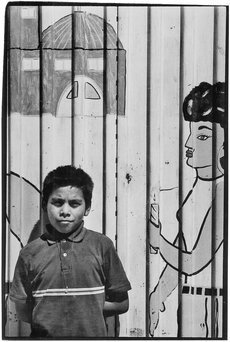

My one sentence review, incidentally, would be "a sprawling, repetitive 1300-page mess that is nevertheless surprisingly organized, cogent and vibrant!" But don't read that yet. I could have just typed that and been done with this review but I'm not there yet. This book has collected dust on my desk, just under my monitor, for half a year, after crouching like a cat by the dinner table on a stack of books on the floor next to the same desk for the previous half-year, all the while with the photo of the rough & ready immigrant laborer on the cover staring up at me to remind me that I really do need to say something about this book on Goodreads before I pass it on to the next reader.

And it's not even about the book's contents that I want to write. Which doesn't seem fair because I thoroughly enjoyed every bit of it. In fact, Vollmann's special talent here is to keep the reader interested even in the dryest, most tedious of his historic sources -- like, literally, tables of census data and farm statistics. In fact, much of the book is short chapters of Vollmann saying: "I'm in a library looking at a table in an old, dusty book (insert descriptions of the book, the paper, the snotty librarian, etc), which lists the number of orange trees in Imperial County in 1782, and I'm imagining myself sitting under one of these trees and eating all the oranges (insert obscenely sensuous description of orange-eating) while dreaming of the future prosperity of my offspring, little suspecting that everything I hold dear is balanced on a thin blade of ice that's melting and/or floating on a shallow lake that's drying out and/or about to be taken away from me by lawyers via some other ominous metaphor ..."

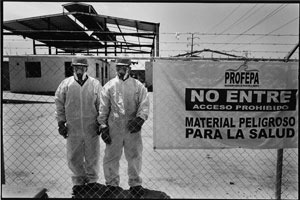

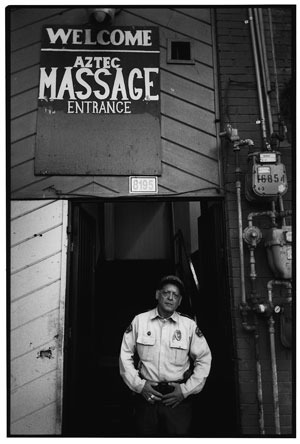

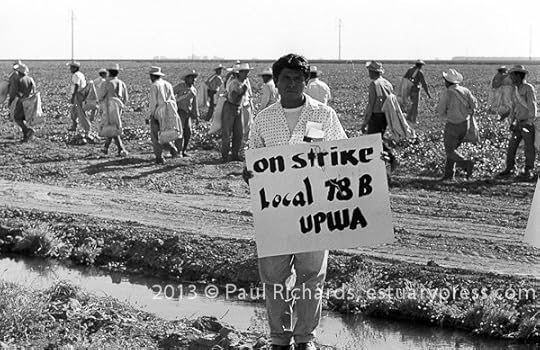

In other words, it's deeply romantic. It's so romantic, in fact, that the entire thing could perhaps be taken as a metaphor for the breakup Vollmann describes in a single chapter about 9% of the way into the book. But the book is not really that story, or his story, or any one story. Instead it's a deeply romantic comprehensive history of this particular region, composed of hundreds of stories of residents and visitors past and present, adding up to the big story of California: irrigation, water in the desert, the Gardens of Eden that the Canal promised, all the people who had faith in that vision and came West to tend that garden -- each of them promised an equal-sized plot of arable land in a great grid of pre-fab prairie Democracy -- and how, in just a few generations, said garden evolved into, if not Hell, then at least Southern California. It's the history of a certain beautiful, antique silly Western dream, and Vollmann dreams it himself, too, just to get inside it, even though he can't really believe in it.

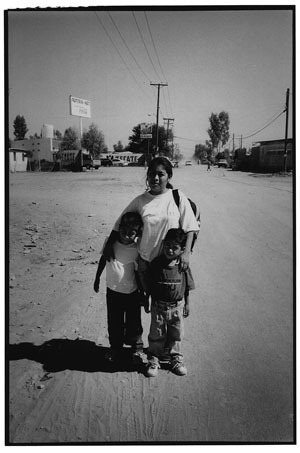

A large middle part of the book is concerned with the city of Mexicali, Mexico, built by Chinese immigrants & repossessed by the Mexican government, home to a kind of Mexican-Chinese culture all its own. Much of it is drawn from articles and advertisments in old newspapers, all repeating the agro-utopian salespitch that brought farmers here from all over the world. Much of it is descriptions of old photographs in those same sources: those salesmen, those farmers, those plots, those diggers of the canal that made it all work, those farmworkers who toiled for those farmers, those financiers and speculators and distributors for whom those farmers toiled -- and after whom the towns were all named.

And, and, and ... you know, I could probably spend the digital equivalent of ten pages summarizing this 1300 page book, but would that make you want to read it, or would it just help you feel okay about skipping it? I don't know. I do know this, though, and this is the point of my review:

Carrying around a four-pound book was a colossal pain in the ass! For three months of my life it was the largest, bulkiest thing on my person. For three months the shoulder strap of my bag dug into my neck, and the corners of the book bounced around on my right kidney when I biked with it. I hadn't had such backpack-blisters since high school, when I had to carry AP Chemistry and Oh, Pascal! to school and back every day ... but at least then I got weekends off! This time, it was constant; I took it everywhere, always, as part of last year's self-improvement project of spending my spare moments in Book-books instead of on Facebooks. In fact I spent some of those three months in Alaska, where I dutifully carried IMPERIAL in my backpack along with tent and sleeping bag and food and clothing and other awkward, bulky, die-without-it items. After each long day of lugging four pounds of William T. Vollmann's brains around in the humid heat, by the time I was finished staking my tent and hyperventilating into my sleeping pad I found myself too damn exhausted to read it! And each time I took this book out of my backpack, and especially every time I struggled to cram it back in, I thought long and hard about Nooks and Kindles and iPads and the lightweight, durable Future Of Reading that they promise.

Because the modern promise of e-books is suspiciously similar in utopian flavor to the hundred-year-old promise of water in the desert. I mean ... hang on, yes, sorry, I do recognize the gap in profundity between dying of famine and not having anything interesting to read. Please stop throwing fruit. But my point is, they're both sales pitches. What Amazon promises readers is what the Imperial boosters promised farmers: a new, better system in which everybody is happier, everything is easier, wealth is shared, and your feedback is important to us.

I have a Kindle. It's light, it's thin, it's digital, and I could have brought it to Alaska instead of bringing the historically pertinent boat anchor called IMPERIAL. But I couldn't have read IMPERIAL on the Kindle. It is "not available on this platform," presumably because the Kindle platform is unable to transmit or encode any of those features of books collectively known as Book Design; it offers only two fonts, only one width of page, a very limited palette of possibilities. IMPERIAL uses book design exquisitely: the aforementioned fonts, illos, footnotes, structures, spreads, maps, et cetera, plus other subtleties I might not even have noticed consciously. The book employs all of it heavily, to great and necessary ends. It's the perfect example of what you can't do on a Kindle, or on a Nook. Maybe on an iPad you could offer something like the original layout; you could even approximate the quixotic structure -- chapters, sections, dates, locations, 'deliniations', 'subdeliniations', 'reprises', and on and on, plus a massive bibliography with its own internal story structure -- in some kind of hypertext TOC, and call that an improvement. But I suspect that e-book would be a pixelly, crunchy, blinky approximation, just enough of a blurry photocopy of the real thing to remind the e-book reader what they're missing.

If you'd asked me before I read IMPERIAL how I felt about e-books, I would have said that I'm not drawn to them, but on the other hand they're sure nifty gadgets: thin, light, wireless, encrusted with delicious clicky buttons and suggestive access ports. They've got an obvious niche: mountain climbers, touring musicians, the elderly, gluttonous readers of disposable romance/western/self-help/bizarro paperbacks ... I wouldn't have said I love them, but I wouldn't have said that I dislike them either.

But it turns out that I really dislike e-books. How much don't I like them? I don't like them so much, I chose to drag this albatross of a cinderblock of a doorstop of a book around with me everywhere I went for three months, instead of using the e-book reader I already own to read one of the e-books that is apparently already waiting inside for me to read it. Thank you Mr. Vollmann, for bringing me this insight.

And I guess that's the point: I love that this book is hard. I love that it's huge and awkward, and that all its major structural indications add up to a sly wink from Vollmann to convey "let's just pretend that I organized this mess, okay?" I love its weird font changes -- even though that sort of thing is almost always annoying, almost universally the sign of a rank amateur who should never have been left alone with a copy of InDesign, let alone given access to Print-On-Demand. I guess I'm just a fan of Vollmann, but also I guess I spent enough time alternately enjoying this book's content and being exasperated by its form -- and then, at times, vise versa -- that I'm over the question of is it good or not, would I recommend it to a friend ... how may stars? Instead I just remember the journey itself, the time I spent with it on the ferry, the time I spent with it at the coffee shop, or in the big chair in the living room, or on a boat in the Sacramento Delta. I remember how, even though I often lost track of the point and questioned whether I really cared that much about Southern California history at all, I was rarely bored, usually amused, often touched ... because Bill Vollmann.

And also, I love it as an object, as a fetish, as a rectangular glue-and-paper thing. I love that its full color dust jacket is scraped and torn at the upper right corner from rough handling, such that along the edge of a tiny half-centimeter rip the glossy plastic top layer is just barely starting to peel from the white paper underneath, and it appears that the cover photograph, of a lone migrant farmer posed by an empty dust road across from a field of blurry crops underneath a blue-white sky, is actually embedded in that plastic top layer of the book cover rather than the paper beneath, such that the peeling-away plastic is sky blue and transluscent, while the paper layer it's splitting from is a rough, fiberous white, suggestive of exactly the kind of raincloud that everyone in Imperial County would love to see in exactly that corner of sky but never, ever will. I love that on the back cover the ISBN number is covered by one of Powell's Books' store labels, and that the store label seems to have absorbed all the grit and sweat and bag-filth that the glossy dust jacket has successfully repelled, so that it looks like a filthy, humble thing clinging to the skirt of a much larger, grander thing, like the intrusion of farmland reality into the fantasy of Imperial real estate. I love the back-flap photo of Bill Vollmann, and the way that he's exactly the same kind of ugly that Elliot Smith was, and how, in just the same way, once you've listened to him enough, that ugliness becomes your new version of beautiful. I even love that there is a digital theft-preventing tracker chip hidden behind that back flap, pasted to the inside of the back cover like a band-aid -- because really, what idiot would shoplift this of all fucking enormous, hard-to-sell books? How would you even do that? Stuff it down your pants? You could be crippled for life! The hardback of IMPERIAL borders on that "too large" size, the size where the very technology of books start to break down, where books get too heavy, too awkward, too difficult to construct, too easy to accidentally split in half, where the human talent for remembering the three-dimensional location of some information -- "that quote, I remember it was on the left side, 1/3 of the way down, somewhere in the last hundred pages" -- starts to get lost in the thickness. It's the sort of thing people are always telling me that people don't make any more. It's anti-futuristic. There's no money in it. Please, give me more.