“But as to names and places, and the conditions in the countries which it all took place, and which may seem very strange to you, I will give you no explanation. You must take in whatever you can, and leave the rest outside. It is not a bad thing in a tale that you understand only half of it.”

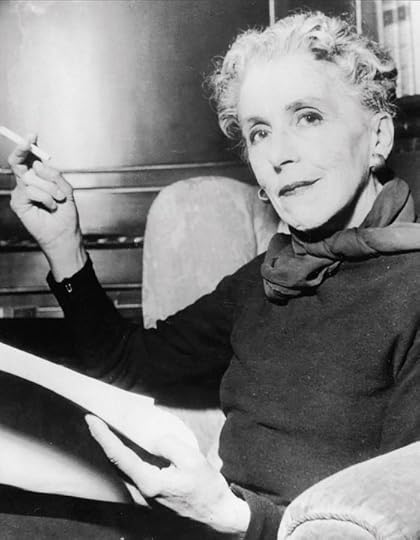

- Dinesen, “The Dreamers”

This is the attitude with which one must approach the stories of Isak Dinesen. It’s that or you’re never going to finish this book. As several of her characters protest to us: “To have only half is better than having the whole.” This is not a case of the lady doth protest too much- in Dinesen’s world, mystery, ambiguity, uncertainty, masks, deceptions-that-may-not-be, what is not said… these are thne rulers worth serving. Maybe not so surprising in something with “Gothic” in the title, but this is no telegraphed “OMG, he’s a vampire!” set of discoveries. (You might not be able to say the same thing about that monkey, but that’s a whole other story.)

Dinesen’s choice of a an early 19th century Gothic setting for this collection seems inevitable. Dinesen comes both to praise the past and to bury it- Published in 1934, these tales are an elegy for the world that Dinesen was born into and which has finally come to a crashing end: the aristocratic, semi-feudal world of pre WWI. What better setting to choose than it’s echo- the aftermath of the French Revolution, and, consequently, the temporary, illusory return to the status quo ensured by the diplomats at the Congress of Vienna.

I do not mean to dismiss these ideas or make it sound like something few could sympathize with, or something in the nature of: ‘oh-those-poor-hereditary-oppressive-classes’. It’s far more than that. Dinesen has many reasons to rend her garments, but they all boil down to this: a lament for Avalon being swallowed up in the mists, for humans no longer having the access to steal fire from Olympus, for Jack’s beanstalk crashing down all over again. The world of Liberte, Egalite, Fraternite is responsible for banishing the giants, and most especially for the fact that we will never be able to believe in them again. It's a world that never was, but it's loss from the imagination is no less devastating for all that. Reality is far too real these days, and when life smacks you down, there’s nothing left to believe in to cushion the fall.

Therefore, it is, more often than not, the old who are the heroes of these stories. These characters are from an earlier era, lingering leftovers, “the last of the old illustrious race”. Their days are numbered, they know the world has moved on and they are considered foolish remnants, and yet, and yet, they have tales to tell that will take your breath away. There are plenty of young characters as well, but the ones we are meant to like are descendants of this older type, or so otherworldly as to not count as a part of the future. To this dying company, Louis-Phillippe, the common place King that everyone knows too much about, is the enemy- and yet one they must support for lack of other choices- to try to keep up the illusion of the gods. As one young aristocratic lady in the early 20th century wrote: “Heaven preserve me from littleness and pleasantness and smoothness. Give me great glaring vices, and great glaring virtues, but preserve me from the neat little neutral ambiguities. Be wicked, be brave, be drunk, be reckless, be dissolute, be despotic, be a suffragette, be anything you like, but for pity's sake be it to the top of your bent. Live fully, live passionately, live disastrously.” Our protagonists here have either done this, spend much time pretending they have, wishing they had, or reaping the consequences for this- trying, as one of the characters in The Dreamers describes it, to get life to drink them down, swallow them whole.

There are many myths, legends, archetypes in play here, but Dinesen has absolutely no trouble weaving them into an exquisite whole, tuning the orchestra into a perfect series of melody and harmony, pronouncements and echoes. She has several main images and references that she works with, each symbol coming back to us repeatedly, refashioned for a new purpose, re-processed through the new mind that needs it. These serve as touchstones to guide the reader through the misty paths Dinesen sets out for us, linking each tale to each. It begins with Adam and Eve (whatever does not?), but then there is Don Giovanni and Faust, the Wandering Jew and the wandering Count Augustus Schimmelman, Timon of Athens and Hamlet. Hamlet, especially, is everywhere in the psyche of these tales- she is from the state of Denmark, after all. We meet the Baron Guildenstern and sup in Elsinore, hell and its ghosts open up to us, characters seem most alive in the state of choosing not to choose. These signposts point our way through the monsters and the saints, the satyrs and the nymphs, and back home again- to giving two young people a whole life in a few dark hours (Deluge at Norderney), to the woman who died and lived on (The Dreamers), the sisters who never left the altar of possibility (Supper at Elsinore), to the most disastrous non-poet who ever lived (The Poet).

These are all gorgeous, achingly felt, beautifully told tales that I plan to revisit over and over again. I’ll say my favorites were the Deluge at Norderney and The Dreamers, because I couldn’t keep the tears inside as I was able to on the other ones, but there wasn’t a one that I didn’t highlight, and that I didn’t get something out of. If I had to pick one, I’d say that The Old Chevalier was my least favorite- as it was a fairly standard one night stand fantasy, but even then, the standard of the storytelling was so high, the structure of it so enchanting, that I’ve rarely minded an old man’s recollection of his whoring days less. This joins the shelf of personal classics, in between Possession and Villette. It’s been a moving journey, and I’m so deeply excited to be back here again someday.

Aw, fuck it, five stars. I can't help it. Point- Dinesen.