Pojedine istorijske teme ne iziskuju poznate autore, ali im prestiž nekog akademika sigurno nimalo ne škodi. Recimo, ako trgujete studiju poput Mejorinog drugog rada, Grčka vatra, otrovne strijele i škorpionske bombe (Overlook, 2003), svjesno to radite kako biste se upoznali sa biološkim i hemijskim ratom u drevnom svijetu, te piščevo ime u tom slučaju obično i zanemarite.

Ipak, kada je Mejorova, inače folklorista i predavač na Prinstonu, objavila svoj najnoviji rad, Kralja otrova (prvo izdanje 2009), njen naslov je bezmalo odmah isplivao na top-10 listama, a onda je nagrađen nekolicinom priznanja i ovjenčan skoro nestvarnim pohvalama od strane američke akademije. Nedugo potom, Kralj je postao i finalista najprestižnije nagrade od svih, National Book Award, ali je najposlije nije dobio. Ovim se stiče dojam da se Mejorino ime iznenada počelo pojavljivati na svakoj drugoj istorijskoj knjizi objavljenoj u Americi u vidu blurb-preporuke, i ova individua najedanput više nije bila opskurni autor.

Donekle je i jasno zbog čega je Mejorova odabrala da baš o briljantnom Mitridatu napiše zahvalno digresivnu i informativnu knjigu, a prvobitni razlog ne glasi zato jer je istoriji već decenijama zaista falilo studijâ o ovom zapravo nejakom ali fascinantnom vojskovođi. Naime, u Grčkoj vatri najviše se, čini se, isticao upravo Mitridatov lik, čiji je život oduvijek graničio sa mitom (da je polovinu života proveo kao Tarzan i da je ujedno znao da se sporazumijeva na dvadesetak jezika), i o čijem životu znamo zahvaljujući biografijama koje su prevashodno pisali njegovi neprijatelji, a to je sigurno nešto što samo može imponovati jednom folkloristi.

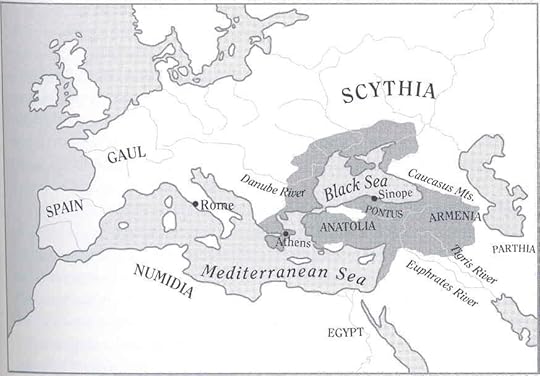

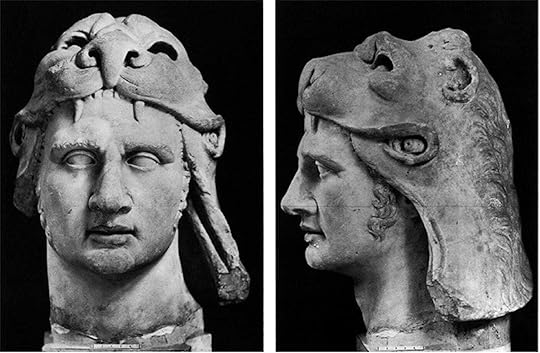

Mitridat VI Eupator Dioniz je rođen u Sinopi, na Pontu (Turska), pokraj Crnog mora, 135. godine prije Hrista, i njegovo rođenje je obilježila blistava svjetlost jedne komete, a isto će, četiri generacije poslije, biti izmišljeno da se zbivalo i iznad Vitlejema, na Istoku, a što će takođe nagovijestiti rođenje drugog znamenitog čovjeka. Mitridat je bio persijsko-makedonskog porijekla.

Time je ostvario onaj Aleksandrov san o miješanoj krvi, a kometa što je ispratila njegovo rođenje navela ga je da kasnije, čim je naslijedio pontsku porodičnu satrapiju, neutemeljeno ustvrdi da njime kola krv Darija I i, sa majčine strane, krv Aleksandra Velikog. Mejorova, međutim, piše da su se dva istoričara nedavno saglasili da uopšte nije nerealno da je pontski kralj zbilja vodio porijeklo od Kira Velikog (utemeljivača Persijskog carstva), i da se zapravo ne radi o pukim lažima njegovih lojalista kako bi se pojačalo kraljevo plemićko porijeklo.

Što se već Aleksandrove loze tiče, Mitridat je navodno bio u rodu sa Barsinom, persijskom princezom koju je zarobio Aleksandar nakon bitke kod Ise (333. godine prije Hrista). Barsina je dobila sina sa Aleksandrom i bila stacionirana u Pergamu, odakle je održavala bliske veze sa Mitridatovom porodicom. Mitridatova mater, Laodikeja, princeza iz Antioha (Sirija) bila je potomak Aleksandrovog generala Seleuka Nikatora, osnivača novog makedonsko-persijskog carstva, što se pružalo od Anatolije i centralne Azije pa do Vavilona i Irana.

San Aleksandra Velikog je bio da spoji persijsku i grčku krv i kulturu, i od toga da načini hibridnu civilizaciju. Ako je vjerovati bezmalo svemu na šta ukazuju istorijski dokazi, onda je Mitridat upravo bio perfektni model onoga što je Aleksandar imao na umu. Štaviše, tokom svoje vladavine, Mitridat se nije odvajao od naslijeđenog plašta za koji je tvrdio da je pripadao nikom drugom do Aleksandru. Ono što ostavlja utisak jeste da se Mitridatova biografija podudara sa standardnim nizom događaja tipično lociranih u životnim pričama mitskih heroja iz raznih kultura.

Mocart je napisao operu o Mitridatu, a Rasin famoznu tragediju, i oba ova rada počinju sa pretpostavkom da slavni kralj naposljetku nije izvršio suicid pošto je bio satjeran u ugao od strane svojeg petog sina koji je poveo pobunu protiv njega.

Vrijedi pomenuti i to da se Makijaveli prvi divio Mitridatovim defanzivnim taktikama.

U mladosti je Mitridat osmislio nesvakidašnji plan za preživljavanje ubistva otrovom (standardni način za ubijanjem plemića s njegove makedonske i persijske strane), pomno izučavajući rukopise na nekoliko jezika, postavši opčinjen time čim je, još kao dijete, izbjegao smrt od ruke vlastite majke i odmetnuo se u šumu; kasnije ju je ubio, kao i svojeg brata, i došao na vlast. Njegov program se zasnivao na konceptu kušanja neznatnih količina otrova, tek toliko koliko da svoj imunitet navikne na njega ako mu organizam ikada više naiđe na taj toksin (isti princip imaju moderne vakcine). Kralj je svakodnevno jeo mrvice raznih toksina i protivotrova, ali se to pokazalo kao problem kad je na kraju odlučio da sebi oduzme život otrovom.

Svoje otrove redovno je isprobavao na zarobljenicima, sve dok nije stvorio složenu mješavinu od pedeset četiri najbolja protivotrova pomiješana sa medom – vjerovatno čuvenim pontskim medom od rododendrona, poznatim naročito po svojem toksinu – od čega je načinio jedinstveni lijek, mitridatij, za vlastitu protekciju. Njegovu smjesu stoljećima su kasnije unaprijedili rimski toksikolozi, kao što je bio Neronov doktor, a zatim i čuveni Galen; on je mitridatij obogaćivao opijumom i pripremao ga trima imperatorima, uključujući i velikog stoika Marka Aurelija.

Znanje o otrovima Mitridat je iskorištavao u borbama protiv Rimljana, gdje je sa sobom poveo i veliki dio Grka iz istočnog dijela Rimskog carstva, koji su naprečac shvatili da ipak više cijene omraženog Aleksandra nego novu rimsku tiraniju. Mitridat, znajući da ne postoji šansa da on sâm porazi moćno carstvo, odlučio je da ga barem ustalasa – ako ne i da pokrene sveopštu revoluciju – uoči i tokom građanskog rata usred Čizme, koji je vremenom odnio 300,000 italijanskih života.

Dvije godine prije suicida, 65. godine prije Hrista, i dok je Pompej Veliki pokušavao da porazi Mitridata, Pompejeva rimska legija se približavala Kolhidi. Mitridatovi saveznici su na put kojim će eventualno proći Rimljani stavili pčelinje saće odakle je točio lokalni otrovni med. Rimski vojnici su počeli da jedu med i redom da gube razum. Mitridatovi saveznici su u toj bici lagano pogubili više od hiljadu rimskih vojnika.

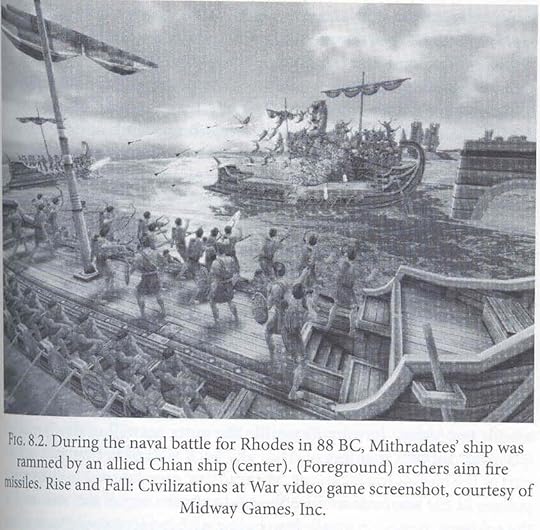

Desetak godina prije Pompeja, na Mitridata je najmanje trećinu svoje vojne karijere straćio i general Licinije Lukul. Naime, odvažni – ili, ako hoćete, sumanuti – Mitridat se usprotivio rimskoj tiraniji 88. godine prije Hrista neviđenim zvjerstvom. Tajno je napravio dogovor sa svojim grčkim saveznicima da se određenog dana zakolje svaki Rimljanin, uključujući žene i djecu, u novoj rimskoj provinciji u Aziji. Toliko su, naime, bili omraženi imperijalni kolonisti da ih je tog dana, navodno, pogubljeno više od 80,000.

Mitridat se, potom, sa brojnom vojskom sjatio na zapad, odlučno poput Hanibala, tako osvojivši Tursku i Grčku, i zaprijetivši da će napasti Italiju. U to doba on je odista smatran za velikog osloboditelja i antiimperijalistu, a naročito među Grcima, odnosno u Atini, koju je posebno inspirisao u ratu protiv Rima.

Rimska armija prvo se borila sa Mitridatom u Bitiniji (sjeverozapadna Turska). Mitridat je na točkove svojih kočija nasadio dugačke kose, koje su se strelovito sjurile na rimske legionare, većinu ljudi na njihovom putu ostavivši bez nogu. Sama ta grozna slika živih ljudi bez ekstremiteta, natjerali su rimsku vojsku u bjekstvo. Ubrzo je Mitridat zarobio rimskog legata Manija Akvilija, sina brutalnog rimskog komandanta kritikovanog zbog trovanja mnogih bunara u Aziji tokom ranijeg rata. Mitridat je paradirao toga zvaničnika na magarcu i onda ga pogubio zbog primanja mita na način koji, danas, većina nas možda ipak i ne bi odobrili – u grlo mu je sipao istopljeno zlato.

Ovakva zbivanja dovela su do dugotrajnih Mitridatskih ratova (u trajanju od 90-63. godine prije Hrista), u kome je niz rimskih generala zaredom poražavao Mitridatovu savezničku vojsku na kopnu i na moru, ali nijedan nije uspio da napokon i uhvati tog monarha; on bi im, taman poput Hanibala, uvijek izmakao u posljednjem trenutku. I tako gotovo tri decenije.

U opsadama gradova u kojima se nalazio Mitridat, prvi put u istoriji su korišćene najneobičnije taktike protiv opsađivača – od rojeva pčela i bijesnih medvjeda koji su huškani na tunelaše, pa do otrovnih strijela sa dvostrukim vrhovima koje su odapinjane u povlačenju. Bedemi Tigranoserte na Tigrisu (istočna Turska), gdje se Mitridat krio kod svojeg zeta, bili su poluzavršeni i grad je vrlo brzo zauzet, ali ne prije nego što su varvari nanijeli velike gubitke Rimljanima. U pitanju je bilo novo oružje velike razornosti.

Istoričar Dio Kasije opisuje kako su Tigranosertani sipali mlazeve vatre po rimskim opsadnim mašinama. Ta čudna vatra je doslovno proždirala sve pred sobom. „Ova hemija“, piše Kasije, „je krcata bitumenom i toliko ognjevita da u trenutku sagorijeva sve čega se domogne, a pri tom ne može biti ugašena nijednom tečnošću.“ Ta likvidna vatra je u stvari bila nafta, a princip na koji će se ona izbacivati na desetostruko veću daljinu, 500 godina docnije, biće poznat kao „grčka vatra“.

Kod opsade Samostate, na rijeci Eufrat, grada što je pripadao Mitridatovom savezniku, još je više gubitaka pretrpjela vojska Licinija Lucija Lukula. Ovog puta to se zbilo od modifikovane vatre isprobane kod Tigranoserte – Plinije je naziva „maltom“, jer je voda ovu smjesu još više rasplamsavala – kada su se rimski vojnici najposlije pobunili i počeli da dezertiraju. Samostata je ostala nezavisna i neosvojiva pustinjska utvrda i narednih stotinu godina, a Lukul je izdahnuo 57. godine prije Hrista od ludila izazvanog otrovom.

Čitajući o Mitridatu saznajemo da je ova Mejorina knjiga prva knjiga o toj istorijskoj ličnosti u posljednjih pedeset godina. Nisam siguran koliko zaslužuje National Book Award, ali bi trebala da bude obavezno štivo svim poklonicima helenističke ere koja je zamrla nedugo nakon Mitridatove smrti.

2012