What do you think?

Rate this book

353 pages, Kindle Edition

First published June 22, 2009

فى البدء كانت كلمة الرب الإله

خلقت حياه

الخلق منها اتعلموا

فاتكلموا

اتكلموا

لا يا مولانا إنت عندك حق و كل العلماء الأجانب بيهروا فى المفيش

أترضى أن يكون أبيك قردا أو ضفدع

هل رأيت يوما جرذا يتحول إلى أرنب

في خطاب أمام الأكاديمية البابوية للعلوم عام 1996، قال البابا يوحنا بولس الثاني: ان “العلم الجديد يؤدي إلى الإعتراف بأن نظرية التطور هي أكثر من مجرد نظرية. من اللافت حقا أنه تم قبول هذه النظرية تدريجيا من قبل باحثين في أعقاب سلسلة من الإكتشافات في مجالات مختلفة من المعرفة. إن التقارب، غير المقصود وغير المفبرك، لنتائح الأعمال التي أجريت بشكل مستقل هو بحد ذاته حجة كبيرة تأتي في صالح هذه النظرية"الغرب الدينى يلحق بركب الحضارة و نحن أبعد حتى من مجرد مناقشة الموضوع بصورة علمية

ما أجمل نومه على كتوف أصحابك

تعرف صادقك من كذابك

تبحث عن صاحب أنبل وش

في الزمن الغش

if any reaction takes a millennium to complete, then the chances are that all the reactants will simply dissipate or break down in the meantime, unless they are continually replenished by other, faster, reactions. The origin of life was certainly a matter of chemistry, so the same logic applies: the basic reactions of life must have taken place spontaneously and quickly.

Each [DNA] letter is copied with a precision bordering on the miraculous, recreating the order of the original with an error rate of about one letter in 1,000 million. In comparison, for a scribe to work with a similar precision, he would need to copy out the entire bible 280 times before making a single error. In fact, the scribes’ success was a lot lower. There are said to be 24,000 surviving manuscript copies of the New Testament, and no two copies are identical.

Each time a human cell divides, you’d expect to see about three mutations per set of chromosomes. And the more times that a cell divides, the more such mutations accumulate, ultimately contributing to diseases like cancer. Mutations also cross generations. If a fertilised egg develops as a female embryo, it takes about thirty rounds of cell division to form a new egg cell; and each round adds a few more mutations. Men are even worse: a hundred rounds of cell division are needed to make sperm, with each round linked inexorably to more mutations. Because sperm production goes on throughout life, round after round of cell division, the older the man, the worse it gets.

Assuming that humans split off from our common ancestor with chimps around 6 million years ago, and accumulated mutations at the rate of 200 per generation ever since, we’ve still only had time to modify about 1 per cent of our genome in the time available. As chimps have been evolving at a similar rate, theoretically we should expect to see a 2 per cent difference. In fact the difference is a little less than that; in terms of DNA sequence, chimps and humans are around 98.6 per cent identical.

there is a statistical likelihood of death regardless of ageing–of being hit by a bus, or a stone falling from the sky, or being eaten by a tiger, or consumed by disease. Even if you are immortal you are unlikely to live forever. Individuals who concentrate their reproductive resources in the earlier part of their life are therefore statistically more likely to have more offspring than individuals who count on an unhurried schedule, reproducing, say, once every 500 years or so, and regrettably losing their head after only 450. Cram in more sex earlier on and you’ll probably leave behind more offspring, who inherit your ‘sex-early’ genes,

Thermodynamics is one of those words best avoided in a book with any pretence to be popular, but it's more engaging if it's seen for what it is: the science of 'desire'. The existence of atoms and molecules is dominated by 'attractions', 'repulsions', 'wants' and 'discharges', to the point that it becomes virtually impossible to write about chemistry without giving in to some sort of randy anthropomorphism. Molecules 'want' to lose or gain electrons; attract opposite charges, repulse similar charges; or cohabit with molecules of similar character. A chemical reaction happens spontaneously if all the molecular partners desire to participate; or they can be pressed to react unwillingly through greater force. And of course some molecules really want to react but find it hard to overcome their innate shyness. A little gentle flirtation might prompt a massive release of lust, a discharge of pure energy. But perhaps I should stop there.

If Martin and Russell are right - and I think they are - [the Last Universal Common Ancestor] was not a free-living cell but a rocky labyrinth of mineral cells, lined with catalytic walls composed of iron, sulphur and nickle, and energised by natural proton gradients. The first life was a porous rock that generated complex molecules and energy, right up to the formation of proteins and DNA itself.

Crick pictured messenger RNA just sitting in the cytoplasm with its codons projecting like a sow's nipples, each one ready to bind its transfer RNA like a suckling pig. Eventually all the tRNAs would nestle up, side by side down the full length of the messenger RNA, with their amino acids projecting out like the tails of piglets, ready to be zipped up into a protein.

One scientist, on first reading Wächtershäuser's wok, remarked that it felt like stumbling across a scientific paper that had fallen through a time warp from the end of the twenty-first century.

But is he right? Harsh criticism has been levelled at Wächtershäuser too, in part because he is a genuine revolutionary, overturning long-cherished ideas; in part, because his haughty manner tends to exasperate fellow scientists; and in part, because there are legitimate misgivings about the picture he paints.

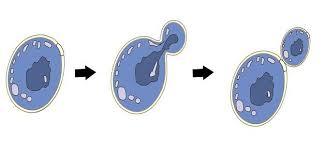

In the face of little solid evidence, I'd like to raise another gloriously imaginative hypothesis from the ingenious duo we met in Chapter 2, Bill Martin and Eugene Koonin. Their idea has two great merits. It explains why a nucleus should evolve specifically in a chimeric cell, notably one that is half archaea, half bacteria (which, as we've seen, is the most believable origin of the eukaryotic cell itself). And it explains why the nuclei of virtually all eukarytoic cells should be stuffed with DNA coding for nothing, completely unlike bacteria. Even if the idea is wrong, I think it's the kind of thing we ought to be looking for, and it still raises a real problem facing the early eukaryotes that has to be solved somehow. This is the sort of idea that adds magic to science, and I hope it is right.