What do you think?

Rate this book

352 pages, Hardcover

First published February 27, 2010

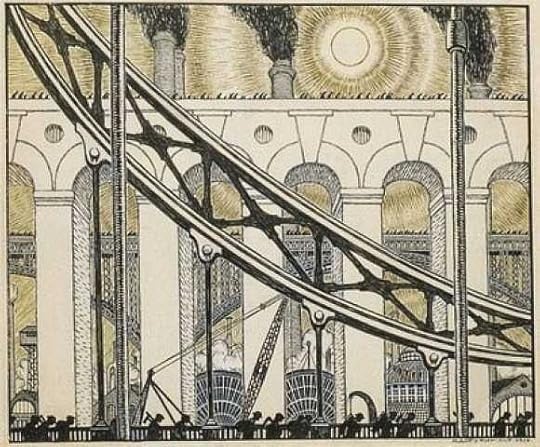

"Silly boy {...} You were trying to rescue the monster." (p. 119)The Dream of Perpetual Motion is stylish, full of lush imagery and ornate phrases, and—yes—it does partake of that most currently modish of styles, its peculiarly backward and timeless sidewise milieu bearing the unmistakable whiff of leather and brass, of zeppelins and pneumatic tubes and the occasional Camera Obscura... yes, the very stench of Steam-Punk. But for all that it's still at heart a boy's own adventure story, told with a patent love of storytelling, and a mordant work of introspection told with a wordsmith's love of words.

"What human on this earth has the power to change a tin man back to flesh?" (p. 171).

"Have you thought about trying to tell a tale in a crowded room, where everyone is shouting to be heard?

"Storytelling—that's not the future. The future, I'm afraid, is flashes and impulses. It's made up of moments and fragments, and stories won't survive." (p. 97)

Miranda, the daughter, serves as the muse for everything that is pure in the world for Prospero so he keeps her hidden away in the skyscraping Taligent Towers. She is kept in a magical playroom where all life's lessons are taught through imaginative play and interactive scenarios with machines. Her only contact in the world is Harold.

The two children become increasingly fond of each other until the inevitable happens and they fall in love.

Harold is then banished from Miranda's life, never to see her again. Then Prospero's steady descent into madness forces Harold to face his own self-doubt and worth to rescue his beloved from the clutches of a madman.