The Way Home is another stellar effort from George Pelecanos, one of the greatest working writers in America today.

Though Pelecanos works under the aegis of crime writer his novels have become vastly more encompassing than that, so acute at displaying American Dreams, lost & found, and so spot on in the rare and exact eye he puts on the working class and under class of the Washington DC area that it becomes increasingly apparent that his work is serious and lasting literature, and that he is as valuable to his time, and as discerning in his judgments as Mailer, Baldwin or Raymond Chandler were in theirs.

The Way Home is a tale of fathers and sons, of Thomas and Chris Flynn. Chris, is a teen screw-up and pot head with a violent streak, who finally goes too far and ends up in juvenile detention for a serious crime. Thomas, his father, is a good man, albeit a man who is sometimes incapable of making the necessary gesture that will calm his addled son and bring him back into the firm and loving embrace of his family. In juvenile hall Chris meets kids, mostly urban blacks, who are tougher than him, who come from backgrounds of such unrelenting hopelessness, devoid of firm guidance, that his own suburban upbringing is brought into stark relief as a thing both fragile and worth retaining.

Chris serves his time, not without violent incident, and maybe even learns a lesson or two. Back outside and a few years down the road he is working for his father’s carpet installing business, even bringing along some of his buddies from the correctional facility. Through no fault of his own events transpire that bring Chris and his friends back into a situation outside the law, where Chris needs to look long and hard about who he really is, what sacrifices he would make, what he would be willing to do in the name of justice and revenge. The people that Chris and buddies run up against are such another order of wicked that the confrontation serves as both a delineation of what is really bad-assed and what is kids pretending and a case study in how the longer you are institutionalized the more dehumanized you become.

Personal Aside: I was a bit of a fuck-up myself as a young man. I can certainly identify with the trajectory of Chris’ journey. My late teens and early twenties included halfway houses, juvenile hall, petty crime, vagrancy, drunk tanks and 72 hr holds in psychiatric wards. It was a rough journey from teen mess to adulthood and I had no paragon of virtue parent like Thomas Flynn to guide the way home. A new and weird wrinkle of reading coming of age texts: for the longest time I identified primarily with the teen/young man making the perilous journey. Now that I have a teen of my own, I feel much more fiercely the pain and hurt of the parents, the frustration, almost endless worry, anger, sadness and joy of trying to help a young man become the best version of himself he can be. This identification with both narrative paths leads to a richer, if somewhat schizophrenic, reading experience.

Some More Words on Pelecanos and The Way Home. Pelecanos started off writing neo-traditionalist noir, hard-boiled tales stuffed with femme fatales, muscle cars and dripping with venomous dialogue and enough pop cultural references and specific musical cues to make Tarentino green with envy. His voice has become mature, a tad mellower, he is now an American traditionalist in the Clint Eastwood vein. And while he can write violence as well as anyone, he is more interested in portraying the consequences of violence now, it’s soul-killing aspects, the way it plagues perpetrators as well as victims, and infects whole communities with it’s virulence.

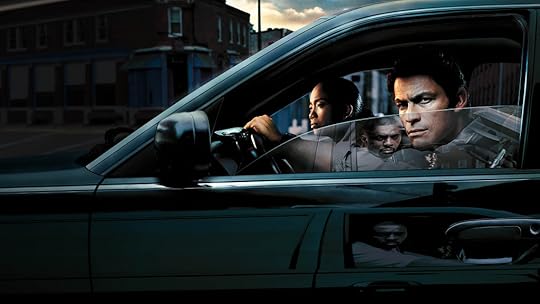

Pelecanos, if he is known at all by the general public, is probably known more for his work on the great TV series, The Wire, than he is for his novels. The Wire at one time had Pelecanos, Dennis Lehane and Richard Price all writing on it, surely the first time three such august novelists worked on one show at one time. Pelecanos lacks the verbal agility and easy lyricism of Price, but he doesn’t give you those awkward moments were his too pretty prose pulls you out of the action as Price often does. His prose is workman like, gritty and heart-felt, never over-wrought or turgid; all his epiphanies are rooted in the character’s development not in empty rhetorical embellishment. He also is not as ham-fisted as Lehane can sometimes be(or as successful-his books sell 1/10th the amount of copies-there’s a crime for you). Pelecanos has written not one but three historical novels(The Big Blowdown, Hard Revolution & King Suckerman) and has caught every bit of each milieu(1940’s, 1960’s, 1970’s) with detail that is true, apt and exciting. Lehane in his big epic, That Given Day, was embarrassingly inept with the African-American characters. Pelecanos, a Greek American, has been writing with power, respect and admirable empathy of Black Americans for his entire career. While it isn’t for me, a white writer, to say how well another white writer ‘gets’ the black experience, the fact that he takes such pains with his craft to get it right is surely worth something.

The Way Home is both a conservative novel in that it upholds the validity of the family unit and the lessons of the father as worthwhile. It is a liberal novel in that it admits that here in America, self-styled greatest nation in the world, that some children are born lost by poverty, race and generations of repetitive violence, only escaping their dire downward trajectories by the utmost effort, luck and the prodigious help of others. Sure Pelecanos believes in The American Dream; he also knows it’s rigged.