What do you think?

Rate this book

254 pages, Mass Market Paperback

First published January 1, 1742

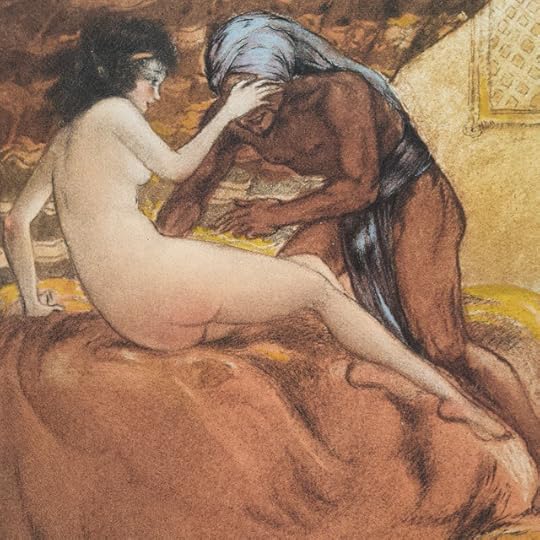

Une simple tunique de gaze, presque toute ouverte, fut bientôt le seul habillement de Zéïnis ; elle se jeta sur moi nonchalamment, Dieux ! avec quels transports je la reçus ! Brama, en fixant mon âme dans des Sopha lui avoit donné la liberté de s'y placer où elle voudroit ; qu'avec plaisir en cet instant j'en fis usage !

A simple gauze robe, almost completely unfastened, was soon the only thing Zéïnis wore; she threw herself down upon me – Gods! with what transports I received her! Brahma, when confining my soul to sofas, had given it the freedom to position itself within them wherever it wished; with what pleasure I made use of that at this moment!

Les femmes accoutumées à nous cacher sans cesse ce qu'elles pensent, mettent sur-tout leur attention à nous dissimuler les mouvemens qui les portent à la tendresse, et telle a peut-être à se vanter de n'avoir jamais succombé, qui doit moins cet avantage à sa vertu qu'à l'opinion qu'elle en a sçu donner.

Women who are used to constantly keeping what they think hidden from us devote all their attention to disguising any gestures that might lead them into tenderness; a woman can, perhaps, congratulate herself on never having succumbed, who owes this advantage less to her virtue than to the opinion she caused to be had of it.

s'il est vrai qu'il y ait peu de héros pour les gens qui les voient de près, je puis dire aussi qu'il y a pour leur sopha bien peu de femme vertueuses.

if it is true that there are few heroes to those who see them up close, I can say also that, to their sofas, there are very few virtuous women.