A magnificent book, I cannot formulate it in any other way. Mind you, this is not a novel, rather a drawn out essay with an autobiographical focus. After all, Hustvedt describes how, from 2006 onwards, she regularly suffers from sudden, severe tremors, and in the book she looks back on her years of searching for an explanation and a solution to it.

So this is a very specialized, rather difficult book to read. Hustvedt tells about her wanderings along psychologists, neurologists, brain specialists, and about her own in-depth study of the state of affairs in those domains, also illustrated with concrete cases she knows herself or she has heard about or read about. She does this in a rather chaotic, meandering way, which according to the reviews enervate many readers. But for me this just was the charm of this book: anyone who is confronted with major illnesses or disorders cannot but work in this way: searching, wandering, asking questions, trying treatmenst, going from success to disappointment and back.

This book provides a staggering picture of a science that knows only a fraction of how man works in that gray zone between neurology, psychology and brain; a science that constantly contradicts itself and swings from one trend or fashion to another, and nevertheless keeps on launching new theories with a air of certainty, or secretly returns to previously stubbornly opposed visions.

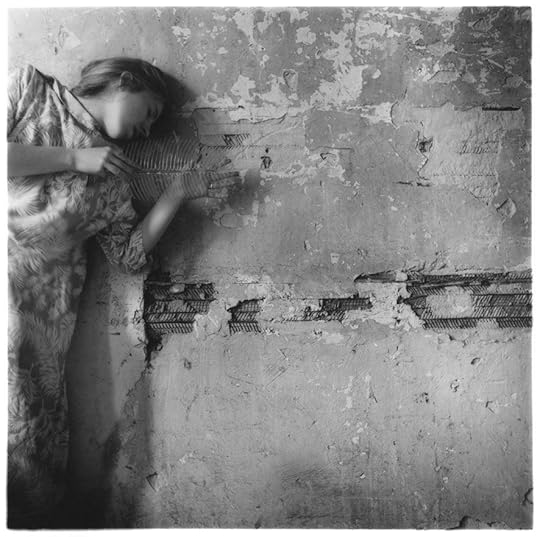

Even Hustvedt herself did not get much further despite all her attempts and perseverence. And I see this too is a source of frustration for many readers. But then they have just missed the point of this book, I would say. Because Hustvedt eventually draws the only possible, pragmatic conclusion: she accepts that her persistent migraine and the tremor-attacks for whatever reason are part of her own identity: "that trembling woman, that's me".

Ultimately, this book for Hustvedt, with all its hesitations and confusion, is not just a plea for acceptance (and fatalism), but it's rather a plea to give space to ambiguity in life, a life with uncertainty (and therefore also with illness and pain), also in the sciences:

"Ambiguity does not obey logic. The logician says, “To tolerate contradiction is to be indifferent to truth.” Those particular philosophers like playing games of true and false. It is either one thing or the other, never both. But ambiguity is inherently contradictory and insoluble, a bewildering truth of fogs and mists and the unrecognizable figure or phantom or memory or dream that can’t be contained or held in my hands or kept because it is always flying away, and I cannot tell what it is or if it is anything at all. I chase it with words even though it won’t be captured, and every once in a while I come close to it."

This is a view I cannot but fully endorce!