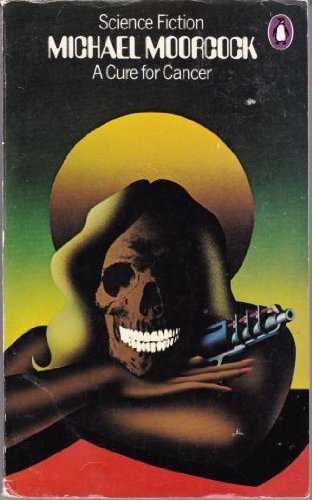

The second instalment of the Jerry Cornelius quartet and our debonair and shapeshifting adventurer is now a negative of his former self: black with white hair. Israel has annexed the Balkans, the entire British parliament has been arrested, and the Third World War is in full swing. Europe is swarming with US ‘military advisors’ who are busy napalming it to oblivion. The president of the United States is rounding up refugees and putting them in internment camps (thank God this is just fantasy fiction from the 1970s). Jerry, armed with his vibragun which has a literally shattering effect on everyone and everything, is kidnapping establishment figures and subjecting them to transmogrification therapy. It’s unpleasant but helps to restore the equilibrium of anarchy. He is also searching for his randomiser machine which has been stolen from him. He intends to use it to accelerate the heat death of the universe. Or perhaps to bring back to life his beloved sister Catherine, whom he accidentally killed in the first book. Or possibly both. Meanwhile his arch-enemy, the obese chocoholic Bishop Beesley, is also in pursuit of the machine with the aim of returning history to a more orderly church-approved epoch. So that’s all perfectly clear then.

The Cornelius Quartet was published between 1968 and 1977, although the first novel was written, in nine days, in 1965. It reflects the period through an infinity of distorting funhouse mirrors. It’s a song for insane times, so there’s no need to point out its continuing relevance to our own. The preceding book, The Final Programme, had a narrative that, although fantastical, was (more or less) linear. In this one, which relocates the Vietnam War to Europe, things are much more fragmented/collage-like/elliptical: a sequence of bizarre and hallucinatory vignettes that are sometimes chilling but also very funny and imbued with an exuberant surrealistic energy. The ‘cancer’ of the title, according to General Ulysses Washington Cumberland, Commander of the US Advisory Force, is nonconformist humanity and the ‘cure’ is napalm. The text is interpolated with extracts from magazines and newspapers. The chapters, all of them short and some just a paragraph or two, have apparently arbitrary titles unconnected to their content: I Died on the Operating Table, Cops who are Hell on Pillheads, UFOs are Unfriendly, Up to No Good, and Some of Them are Truly Dangerous. All of this adds to the pervading apocalyptic sense of a world off its hinges.

This is a disorientating read and is clearly meant to be. On reflection I think my opening paragraph makes it sound rather more coherent than it actually is (yes, honestly!). Moorcock has said that his aim with the Cornelius books ‘was to liberate the narrative; to leave it open to the reader’s interpretation as much as possible - to involve the reader in such a way as to bring their own imagination into play’. He succeeded. It’s as though every known genre has been fed into Jerry’s randomiser: Swiftian satire, experimental literature, dystopian nightmare, pulp fiction, SF, James Bond, comic books, surrealism, erotica, existentialism, commedia dell’arte, psychedelia, countercultural polemic, absurdism. Does it make sense? Don’t be silly, but that’s reality for you. At the same time it makes perfect sense: Moorcock’s surreal approach taking you closer to the insanity of the Realpolitik of the Nixon era than realism could. Jerry Cornelius knows how to survive, and even enjoy himself, in a hellish and meaningless multiverse. The puzzled reader might be best advised to do as Jerry does and go with the flow. It’s a vertiginous adventure. And, as Jerry says, there’s ‘nothing like adventure’.