What do you think?

Rate this book

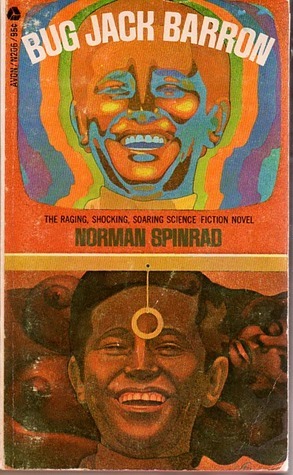

327 pages, Mass Market Paperback

First published January 1, 1968

Picked this up because I was getting annoyed at the Library of America’s The Future Is Female volumes; found myself more annoyed with this, the unadulterated sexism and tardy pace of it; put this down to read a David Brin novel; which did the trick, when I came back to Spinrad he seemed fast-moving and egalitarian—

Anyway this is not a good book. To some extent I wonder whether this is entirely Spinrad’s fault. It’s serialized in six parts over a little under a year in New Worlds, nominally a monthly magazine, but one famously running into difficulties here after a large chain refused to stock them, citing (in part or in whole? I’m not sure) the sexually explicit nature of Bug Jack Barron. In December ’67 the editors note the next issue contains a “substantial installment of Norman Spinrad’s brilliant novel BUG JACK BARRON, which will continue to get better and better as it progresses.” This is the only instalment which—on perhaps a slightly cursory glance—had any real difference from the 1992 paperback I was reading, which still had a copyright date of 1969. (I was baffled by a couple of references to the election of Reagan as a pure image candidate, thinking they had been inserted and botched the timeline, and then realised they were references to him as governor.)

By February ’68, when the next issue makes it out, they call it “our serial”, hyping the then-26 Spinrad, who is quoted as (oh dear) attempting to write “a coherent Nova Express”—so, yes, partly on him, sure; four monthly issues later, in October, they note “for space reasons we have had to condense the conclusion of this novel to be published in 1969 by Avon books,” though it doesn’t condense so much as omit, about a quarter of the word count—and the only section in which things happen, one character attempting to have another killed, and a third killing herself, and the revelation of what’s actually going on with the whole mystery of the book’s plot. I go into all this for a couple reasons: I suspect part of the reason this book restates itself so much is that it was conceived as a serial, though I haven’t seen anything definite about that; also, by the time it was actually completed, history had awkardly left it behind.

—

In the 80s of Bug Jack Barron (I don’t think Spinrad has a date in the text, though I could be wrong; I wound up reading this marginally less slower than it was serialised, and have no intention to reread the earlier parts) the Democrats, after their victories of the 1960s, are seen as twenty years into an immovable thousand-year reich, the Republicans basically irrelevant, the Democrats in fact seriously pressured from the left by a new political party, one representing the ideas of the campus radical and the hippy, one which I’ve forgotten the name of, one formed by the titular Jack Barron before he went apostate and showbiz. Of course, by the time the book came out in hardcover Nixon was in the White House. Now, the point of SF isn’t the literally predictive, and so on and so forth, but this does suggest a woefully blinkered reading of the present; in 1966 it was pretty clear that the New Deal and the Voting Rights Act were not particularly worthy guarantors of Democrat presence in the halls of power. It’s odd—given how cynical, perhaps excessively cynical, perhaps adolescently cynical, this book is—that Spinrad didn’t notice that. But, yes, this is a book where the High 60s Social Moment is extended impossibly into the future; it’s very funny to have low-rent hippy apartments in 1980s manhattan, all dope no crack; Jack is described as a hippie Kennedy or a squarer Dylan (who, delightfully, has also been assassinated); for no particular reason, I was picturing him as Mastroianni in La Decima Vittima.

Barron, as the novel starts, presents a hit TV show, the titular Bug Jack Barron. This is the biggest show on TV, we are told; Barron is an opinion-maker; in many ways his social function seems to be more like the right-wing talk-radio giants of the actual 80s, though we do hear several times of the virtuousity with which (bless!) the production staff do advanced graphical things like put a caller’s image into one-quarter of the screen while Barron himself occupies three-quarters of it. The big social issue is one Benedict Howards’s ‘Foundation for Human Immortality’, which is doing cryo-freezing with an effective government majority; Howards tries to enlist Barron to sell the public on him at the same time as Barron’s old political cronies try to convince him to run for president on a joint ticket with the Republicans. Howards has some people killed, because, we learn, i. the Foundation actually has learned how to render people immortal ii. the process revolves around massively irradiating children and removing certain glands to implant them in the beneficiaries; the children i. are mostly black ii. will die certain, miserable deaths of cancer. Howards convinces Barron’s ex-wife Sara to go back to him to sell him on being Howards’s man.

—

The book is more readable as a serial: it restates the stakes and what every party knows about what’s going on every time they become focal. It feels a bit like neither Moorcock (or whoever) at New Worlds nor his editors at Avon quite took Barron in hand enough to make the book work at book length. It’s also deeply over-written in a way that doesn’t quite land but is bearable, even charming, in small doses: the random page I opened to includes both describes an apartment as “a straw-mat-floored studio room, low primary-colored geometric-precision Japanese furniture hard-edged in the neutral, off-white pseudolantern overhead light, thousand-years distant in cool squares and rectangles from ricky-ticky neon-baroque Village streets” and features the sentence ��And he looked into her pool-dark eyes that knew holes with no bottoms inside, his locked on hers locked on his like x-Ray cameras facing each other in feedback circuity between them gut to gut belly to belly big dark eyes eating him up saying: I know you know I know we know we know we know—endless feedback of pitiless scalpels of knowledge.”

I do wonder if there’s meant to be more tension in all the Tarzan/Jane/balling/making-love content, if that’s meant to be a part of the appeal, either pruriently (there are sentences written just as extra as that one I just quoted describing e.g. a blowjob) or thematically: if we’re meant to take this seriously as a novel with things to say about male-female relations. I had a note on my phone that said something to the extent of “just summarising that episode I just read would be a good demonstration of the novel’s misoygny”: reader, I don’t know which episode I meant. It was either Jack’s feelings about his secretary’s feelings for him or Sara’s feelings about Jack’s feelings for him; one of those included the phrase “the soft womanflesh of her mind”; a later passage on Jack’s feelings about Sara’s feelings for him described them as “c—tfelt”.

I recourse to the “—" there because I don’t know what Goodreads community standards are but there are probably certain words I want to avoid, one of which is coming up: the book is also pretty (grimaces, yanks collar, exhales from corner of mouth) when it comes to race. In Howards’s descent towards madness later in the book he keeps having the intrusive image of the black children he’s killed, which he internally verbalises “maggots eviscerated n—rs”; this phrase, variations of it, on maybe a dozen pages, which, yes, we understand is the thoughts of a bad man, but also very clearly a 26-year-old being edgy.

But, then, on the first page, we had Jack’s old political acquaintance, the black Mississippi governor Lucas Greene, leaving a meeting with one Malcolm Shabazz: “Prophet of the United Black Muslim Movement, Chairman of the National Council of Black Nationalist Leaders, Recipient of the Mao Peace Prize, and Kingfish of the Mystic Knights of the Sea … neither more nor less than a n—r. He was everything the shades saw when they heard the word n—r: Peking-loving ignorant dick-dragging black-oozing ape-like savage. And that cunning son of a bitch Malcolm knew it and played on it, making himself a focus of mad white hate …”—never quite specific how this Malcolm Shabazz relates to the one we know better as X, who was two years dead when the novel’s first instalment came out. Anyway, that probably tells you as much as you ought to get—the black character we get to be in the head of immediately identifies black radicalism as insincere—which is perhaps complicated by Greene himself turning out to be a phony, one who built himself as expensive governor’s residence in a for-show state capital while a bankrupt Mississippi descended into poverty—though probably not complicated in a particularly not racist way.

—

Mystifying to imagine reading this in the serial: being told all the plot had happened between part five and part six, and that it was resuming right after a lead character’s suicide. Barron has told Sara about the cancer-children aspect of the immortality Howards has, by now, granted them with; their last night together they can’t bear to touch each other; the next evening Sara takes acid and jumps from Barron’s balcony, killing herself to convince him to demolish Howards on his TV show, which he does. In a section that might as well be labeled ‘ironic coda’ Howards languishes in a mental institution, reflecting on how he has an immortal lifespan in which to be proved i. sane and ii. not guilty, Lukas Green reflects on the political ramifications of events for his future career ("stop crying, you n—r you, you knew that was the way it had to be"), and Barron goes back to the secretary he was schtupping before he returned to his ex-wife.