What do you think?

Rate this book

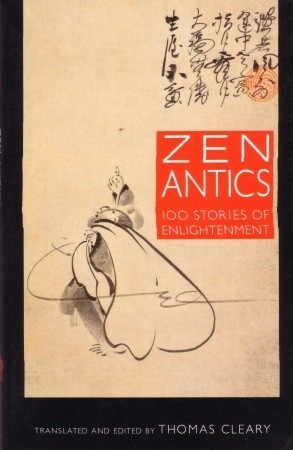

99 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 1993

Izu studied Zen with Hakuin for a long time. As a teacher in his own right, Izu inherited the harsh manner of the redoubtable master Hakuin but was even sterner. Whenever he would receive people asking about Zen, he would lay a naked sword next to his seat. If they were hesitant or argumentative, he would chase them out with the sword.

Settan once wrote a set of guidelines for Zen monasteries. “An ancient said that Zen study requires three essentials. One is a great root of faith. The second is a great feeling of wonder. The third is great determination. If one of these is lacking, you are like a tripod missing a leg.

Many people of both ancient and modern times have awakened to the way and seen essential nature in the midst of reality. All beings in all times and places are manifestations of one mind. When the mind is aroused, all sorts of things arise; when the mind is quiet, all things are quiet. When the one mind is unborn, all things are blameless. For this reason, even if you stay in quiet and serene places deep in the mountains and sit silently in quiet contemplation, as long as the road of the mind-monkey’s horse of conceptualization is not cut off, you will only be wasting time.

The third patriarch of Zen said, ‘If you try to stop movement and resort to stillness, that stopping will cause even more movement.’ If you try to seek true suchness by erasing random thoughts, you will belabor your vital spirit, diminish your mental energy, and make yourself sick. Not only that, you will become oblivious or distracted and fall into a pit of bewilderment.

Harmonization with the ineffable wisdom inherent in everyone before getting involved in thinking and conceptualization is called meditation; detachment from all external objects is called sitting. But closing your eyes and sitting there is not what I call sitting meditation; only sitting meditation attuned to subtle knowledge is to be considered of value.

I too toiled over the occurrence of thoughts when I was young, but suddenly I realized that our school is the school of the enlightened eye, and no one can help another without clear perception. From the beginning I transcended all other concerns and concentrated on working solely on attainment of clear vision.

Everything is conditional and ultimately empty of inherent selfhood.

My way is right there, wherever I happen to be. There is no gap at all.

All confusion is a matter of revolving in vicious circles of delusion because of using thoughts. When angry thoughts come out, you become a titan; craving makes you an animal; clinging to things makes you a hungry ghost. If you die without giving these up, you revolve in routines forever, whirling in the flow of birth and death.

In this world

where words do not remain at all,

any more than the dew

on the leaves,

whatever should I say

for posterity?

As Kokan was nearing death, his foremost disciple asked him for a final verse. He hollered, “My final verse fills the universe! Why bother with pen and paper.”

At dawn, in response to the temple bell, the universe opens;

The orb of the sun, bright, comes from the Great East.

What this principle is, I do not know;

unawares my jowls are filled with gales of laughter.

First days of Spring – the sky

is bright blue, the sun huge and warm.

Everything’s turning green.

Carrying my monk’s bowl, I walk to the village

to beg for my daily meal.

The children spot me at the temple gate.

Who says my poems are poems?

My poems are not poems.

After you know my poems are not poems,

Then we can begin to discuss poetry.