What do you think?

Rate this book

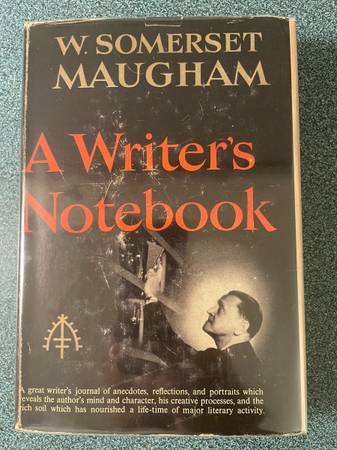

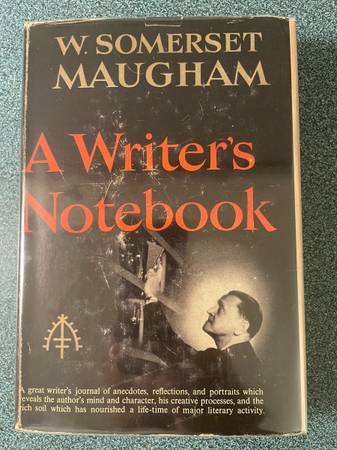

367 pages, Hardcover

First published October 1, 1949

“I’m glad I don’t believe in God. When I look at the misery of the world and its bitterness I think that no belief can be more ignoble.” [p.63]

“After all, the only means of improving the race is by natural selection; and this can only be done by elimination of the unfit. All methods which tend to their preservation – education of the blind and of deaf-mutes, care of the organically disease, of the criminal and of the alcoholic – can only cause degeneration.” [p.64]

“The ethical standard is as ephemeral as all else in the world. Good is nothing more than the conduct which is fittest to the circumstances of the moment...” [p.65]

“Harvard’s role in the movement was in many ways not surprising. Eugenics attracted considerable support from progressives, reformers, and educated elites as a way of using science to make a better world.” [March-April 2016, p.48]

“Harvard was more central to American eugenics than any other university. Harvard has, with some justification, been called the “brain trust” of twentieth-century eugenics...” [ibid.]

“We do not want word to go out that we want to exterminate the Negro population, and the minister is the man who can straighten out that idea if it ever occurs to any of their more rebellious members.” [see “What Margaret Sanger Really Said About Eugenics and Race,” Time Magazine, Oct, 14, 2016]

“The power of great joy is balanced by an equal power of great sorrow. Enviable is the man who feels little, so that he is unaffected either by the extremes of bliss or of grief.” [p.21]

“How much greater would human happiness have been if gratification of the sexual instinct had never been looked upon as wicked. A true system of ethics must find out those qualities which are in all men and call them good.” [p.75]

“Plumbing. When you consider how indifferent Americans are to the quality and cooking of hte food they put into their insides, it cannot but strike you as peculiar that they should take such pride in the mechanical appliances they use for its excretion.” [p.345]

“When I was engaging two coloured maids to look after me the overseer of the plantation who produced them...” [p.342]

“If he’s capable of feeling he must be capable of remorse, and when he considers what a hash he’s made in the creation of human kind can he feel anything but that? The wonder is that he does not make use of his omnipotence to annihilate himself. Perhaps that’s just what he has done.” [p.346]