What do you think?

Rate this book

350 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 1996

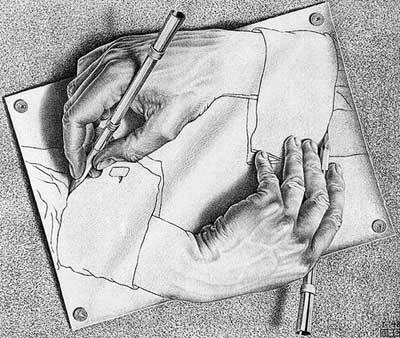

A purulent night wrapped every corpuscle into being, in a dark and hopeless schizophrenia. The universe, which was once so simple and complete, obtained organs, systems, and apparatuses. Today, it’s as grotesque and fascinating as a steam engine displayed on an unused track at a museum. It demonstrates its rods and levers under a bell jar. And until the bell of our minds is incorporated into the universal desolation, it will function as an internal organ reflecting the whole, the way a pearl reflects the martyred flesh of an oyster.

The universe at that time consisted of the three rooms in our home and a few annexes, extended like spider legs, with an ambiguity all the greater for their distance. There was a first zone, semi-real, where I could move by myself, more or less safely, after which followed the city streets, which my parents created by walking between real and foreign places. Only my mother and father, between whom I walked through fortresses and basilicas, depots and castles of water scraping clouds like flames on yellow heavens, only my gigantic masters and friends, clasping my fingers in their great, warm hands, talking quietly over my head and pulling me through round piaţas with fabulous statues in the center, could pacify the endless dominions of chaos. Like a reflex arc, like the engram of memory, like the melting of marble steps under millions of feet, some streets, the ones we took more often, solidified, they gained a consistency, they were colored in familiar shades, detaching from the unreal gray that surrounded them.

Forse nel cuore più profondo di questo libro non c’è nient’altro che un urlo giallo, abbacinante, apocalittico...

Mircea Cărtărescu sa essere talvolta brutale e nichilista, ma anche malinconico e delicato; la sua è una penna impeccabile e implacabile imbevuta di lirismo. Ciò che più mi ha impressionata è stato il suo stile di scrittura composto da un lessico baroccheggiante e descrittivo che vira con consapevolezza verso la poesia – in effetti Cărtărescu nasce come poeta e solo successivamente si dedica alla prosa - e il simbolismo immaginifico; devo ammettere che alcuni termini utilizzati non li conoscevo ed è stato insolito tornare alla mia vecchia abitudine di stilare un elenco di questi lemmi, tirare fuori il vocabolario e consultarlo… Sono ripiombata ai tempi del liceo.