What do you think?

Rate this book

300 pages, Paperback

First published December 1, 1999

"O then I long to spring

Through the charged air, a wastrel, with not one

Farthing to weigh me down,

But hollow! foot to crown

To prance immune amongst vast alchemies,

To prance! and laugh! my heart and throat and eyes

Emptied of all

Their golden gall."

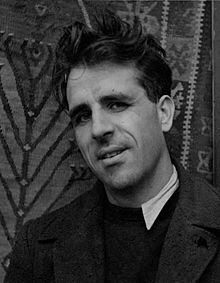

He observed that in the past people used to talk of ‘a strong personality’, whereas now they spoke of a ‘psychological kink’. For him, a character like Gertrude, the Countess of Groan, would have become neurotic ‘if she hadn’t allowed herself to have all those cats’. People are neurotic, he opined, precisely because ‘they’re frightened of walking down the street with fifty cats following behind them’.

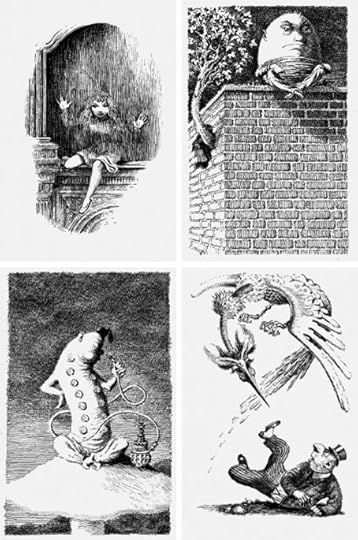

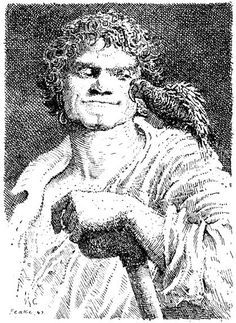

The main source of inspiration for the nascent novel was clearly the setting, the castle of Gormenghast itself, rather than the characters. In fact, it might be said that once Mervyn had imagined Gormenghast the place itself generated characters to inhabit it, and the story-line came only after that, developing organically rather than according to any preconceived plan. Consequently a plot summary of the Titus books misses the whole point, for is obliged to omit the purely descriptive passages and neglects the interpenetration of person and place.

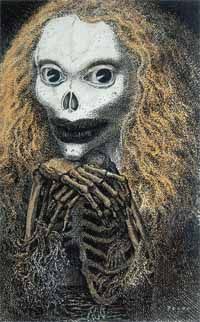

Appreciation of the Gothic in Mervyn’s writing thus depends upon the reader’s ability to share in his sombre humour; for the sympathetic reader his novels are darkly comic, mocking our fears just as Steerpike mocks the Twins’ with Sourdust’s head on a broomstick (and other fears, too, as Barquentine buries the remains of Sourdust with a calf’s skull substituting for the missing cranium). On the other hand, if the humour fails, then you have unalleviated gloom and horror.

Since Titus Groan is often called an intensely visual work, let me underline how much the mode of representation is physical rather than visual. Take the justly famous opening sentences… There’s not a colour, not a line, nothing to instruct the eye. It’s all in the feeling, the physical sensation of the ‘massing’ of the stone, the ‘ponderous quality’ of the architecture, the sprawling humble dwellings that ‘swarm’ around the foot of the castle walls and cling ‘like limpets to a rock’. [...]

Most readers will quite unconsciously translate these physical and auditory terms into their favoured mode of internal representation, the visual, with the result that they believe the books to be highly visual. In this way, reading the Titus books affords them an intense multi-sensory experience.