Critical Response: My First Goose by Isaac Babel translated by Walter Morison

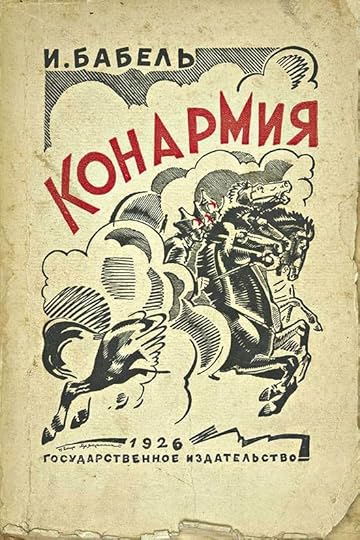

My First Goose appears as part of Red Cavalry, which is essentially a novel told with short stories. Red Cavalry was first published in 1929 and is generally considered Babel’s finest work in short form. The larger plot is based on Babel’s own experience as a youth fighting among the ranks of Budenny’s notorious Cossack band. The plot of My First Goose details in first person perspective the appointment of a young law student to a band of Cassock soldiers near the Chugunov-Dobryvodka front. The structure is spare and almost dream-like; it could be described as an initiation story, hinging on the tension of the outsider receiving a test or rite by which he may become an insider. Seen another way this story is also a psychological depiction of war’s mental/emotional toll.

Characterization is essential to the piece as the development of Commander Savitsky into a sort of omniscient antagonist very subtly becomes the essential narrative arc. The story begins with a detailed description of the Commander—the most detailed of all the characters in the short piece. The greatest clue to story’s primary tension is given in the line: “His long legs were like girls sheathed to the neck in shining, riding boots.” The strange impression of this simile is heighted by an implied sword-like aggression or captivity, and serves to cast the Commander in starkly ironic light. Additionally, the arc of the story is achieved as the narrator curls up to sleep having passed his extemporaneous initiation at no small cost to his mental health, described thus: “We slept, all six of us, beneath a wooden roof that let in the stars, warming one another, our legs intermingled. I dreamed: and in my dreams saw women…” It is with this eerily fitting choice of images—legs and women—that Babel completes the story’s resolution. And, what synecdoche is thematically more fitting to a soldiers life—particularly that of the cavalry always on the move—than to ruminate on the legwork of marching and running to battle. And in questions of why we fight, perhaps the most poignant is why men are driven to war, and women are essentially motivated by peace.

This thematic tension is initially heightened through an ironic passage of dialogue in which the Commander smilingly dictates orders for some unfortunate soldier to either encounter the enemy and destroy them or face his own destruction at the Commander’s hands. The Commander then turns his attention on the narrator with “grey eyes that danced with merriment,” and proceeds to mock him for his learning, picking in particular the narrator’s glasses as an object of slang derision.

And, it is worth a pause here to note a masterful stroke of insight on the writer’s part. After this passage of devious jibes, Babel very slyly slips in a brief lyrical passage describing the village and the “dying sun… giving up is roseate ghost to the skies.” In a sentence describing the height of beauty, Babel mingles imagery from the grave and maintains his tension while giving the reader both orientation and a chance to breath, before being structurally enjambed with the psychopathic Cossacks, which our poor narrator must impress.

There is also a subtle psychological footnote made about the narrator in so far as the quartermaster who is carrying his trunk offers a clue as to how the narrator must pass Cossack’s test and simultaneously shows himself be a both a little crazy and unwilling to trust the narrator: “He came quite close to me, only to dart away again despairingly.” This description of a marginal character works to both hint to the reader some of the cues and body language, which the narrator is experiencing without going into detail about each person’s reaction to him.

The Cossacks are depicted as more insane than the quartermaster, as they trash the narrator’s belongings and mock him with the shouts of combat. Lyric beauty itself is then ironically employed to illustrate the narrator’s plight with a paragraph that delves into a scene of beauty and torment ending thus: “The sun fell upon me from behind the toothed hillocks, the Cossacks trod on my feet…”

It is then that the narrator fixes on the object of his emancipation—someone weaker than himself, namely the landlady. He proceeds to dominate the landlady, demanding food, refusing to acknowledge her weak pleas, cursing her slowness, and then brutally killing a goose in a passage that is as poetic as it is visceral. And, that’s it. By ruthlessly crushing the one figure smaller than himself, the narrator has passed the test. The Cossacks open their ranks to him, and the narrator even manages to display his literacy in a way that the illiterate madmen can understand by reading Lenin’s speech like a stand-up routine. The double irony is that it is in this fashion that the narrator spies out “exultingly the secret curve of Lenin’s straight line,” something that even resonates with his street smart new comrades.

Throughout My First Goose (including the title) descriptions and symbolism are used in unique even unbalanced ways: the Commander is described has having “a smell of scent;” the narrator’s response to the Commander causes him to “envy the flower and iron of that youthfulness;” the smoke of homes in the village mingle “hunger with desperate loneliness” in the narrator’s head; the Cossacks observe his violent outburst “stiff as heathen priests;” even the moon hangs above them “like a cheap earring.” These subtle details give added meaning to final line’s violent lushness.

An enviable work of biographical fiction, this piece seems both experimental and classical. Some figures move through the tale as though allegories of themselves, others seem to be so mud-drenched and sunburned they defy description, but each is vivid in his or her own turn. The story arc itself is so charged as to nearly become a character itself, and the resolution, while concise, is anything but abrupt as the words and impressions of the piece seem to filter through the readers mind like feedback.