What do you think?

Rate this book

Célébrée en 1963 par le prix Renaudot pour Le Procès-verbal, puis en 1980 par le Grand Prix Paul-Morand décerné par l'Académie française pour Désert, la plume de Le Clézio s'affine encore ici, dans la droite lignée des romans d'apprentissage. --Laure Anciel

374 pages, Pocket Book

First published January 1, 1985

What now -- what now to meThis bitterness does not emerge in the course of The Prospector, but the withering irony of a life wasted hunting for an elusive treasure did hit me with the force of a blow to the head as I finished Le Clézio's wonderful novel.

Are all the jabbering birds and foolish flowers

That clutter up the world? You were my song!

Now, let discord scream! You were my flower!

Now let the world grow weeds!

Now I understand how deluded I was: history happened here [Mauritius] as it did everywhere else; the world was not the same anywhere. There have been crimes, transgressions, a war, and because of it our lives have come apart.It is not just history -- World War I and its dire effect on the colonial peoples -- but nature herself. There are two great hurricanes in the novel, one on Mauritius in 1892 that destroys the L'Étang cottage at Boucan, and one on Rodrigues Island in 1922 that puts an end to Alexis's second attempt at seeking the treasure.

Zweeke the sorcerer said, "You ask me, my father, to tell you of the youth of Umslopogaas, who was named Bulalio the Slaughterer, and of his love for Nada, the most beautiful of Zulu women. Each one of those names was buried deep in me, like the names of living people.Throughout the book, Alexis conjures with the sheer sound of naming things: islands, mountains, rivers, trees, plants, birds. The book is written entirely in the first person, with very little dialogue, giving the rhapsodic effect of a waking dream, even amid the horrors of the Western Front:

What do these rivers look like… the Yser, the Marne, the Meuse, the Aisne, the Ailette, the Scarpe? They are rivers of blood flowing under low skies, thick, heavy water carrying debris from the woods, burned beams, and dead horses.Or here, near the end, when the author merges past and present in timeless simplicity:

Our life on Mananava, far from other people, is like an exquisite dream. […] At dawn we glide into the forest, which is heavy with dew, to pick red guavas, wild cherries, and cabbages, Madagascan plums, bullock's hearts, and bredes-songe and margosa leaves. We live in the same place as the maroons in Senghor and Sacalavou's time. Look there! Those were their fields. They kept their pigs, goats, and fowl there. And over there they grew beans, lentils, yams, and corn.I have now read four Le Clézio books and some stories. All seem to be to some extent autobiographical, written out of a double loss—his family removed from their home in Mauritius, and the author not seeing his father for the whole of his early childhood. The books feature travel and hardship, young protagonists in pursuit of some quest. They are filled with an aching nostalgia for a lost past, and with awe of the wild and ancient places of the earth and the secrets they may hold. In some ways, Le Clézio is a century behind his time; besides Rider Haggard, you can see the influence of Kipling and especially of Conrad. But his currency is modern; he deals in dreams. Let him once work his magic, then see if you can cast off his spell.

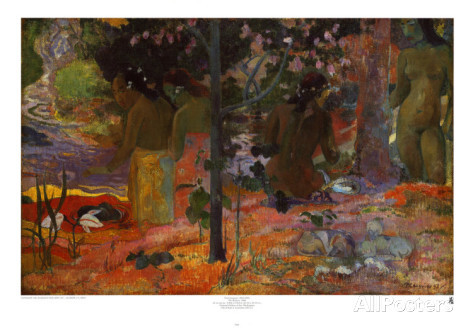

The cover is a detail from Paul Gauguin's 'The Bathers' 1898

The cover is a detail from Paul Gauguin's 'The Bathers' 1898

For my grandfather, LéonOpening: Boucan, 1892: AS FAR BACK as I can remember I have listened to the sea: to the sound of it mingling with the wind in the filao needles, the wind that never stopped blowing, even when one left the shore behind and crossed the sugarcane fields. It is the sound of my childhood.