What do you think?

Rate this book

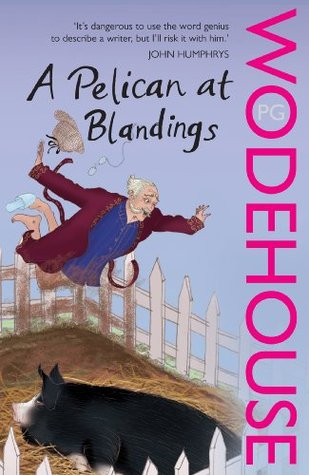

226 pages, Paperback

First published September 25, 1969

"One of the lessons life teaches us is never to look for instant bonhomie from someone we have rammed in the small of the back and bumped down two flights of stairs. That sort of thing does something to a man. I noticed when I was talking to him that the iron seemed to have entered into his soul quite a bit." (196)Alas, after finishing the Jeeves and Wooster series, I have now also finished the Blandings Castle series. A Pelican at Blandings wasn't among the best, but it was entertaining enough. Thankfully, Wodehouse wrote plenty of other stuff—which I will now be systematically hunting down.