What do you think?

Rate this book

456 pages, Paperback

First published February 5, 2009

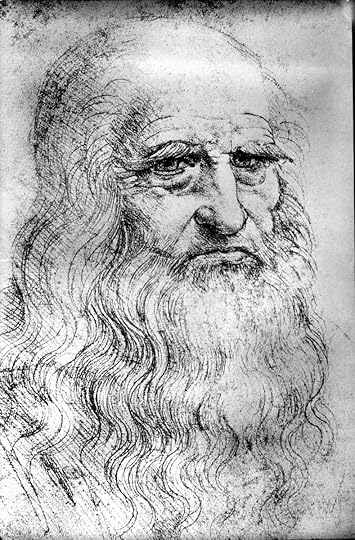

I would rather be in hell & converse with great minds upon state questions than live in paradise with the rabble I saw just now....for in the latter, one would meet no one but wretched monks & apostles, whereas in hell, one would be in the company of cardinals, popes, princes & kings.Finally, Cesare Borgia, who greatly influenced Machiavelli, was a ruthless thug, often wearing a mask to hide fast-encroaching syphilis scars on his face and he ultimately died a vicious death in his early 30s as his power & prestige waned and new forces took control of his former dominions.