What do you think?

Rate this book

639 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 1995

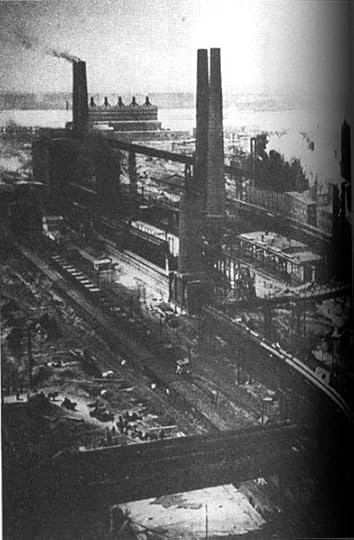

But then the conductor bellowed, “Magnitogorsk!” Could this barren, windswept wasteland be the famous World Giant? The colorful journalist Semen Nariniani disembarked from the train, looked around, turned to the station man, and asked, “Is it far to the city?” “Two years,” the man answered.