What do you think?

Rate this book

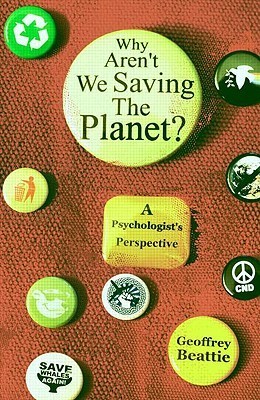

284 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 2010

"One statistic that jumped off one of his original reports was that it would take thirty-two years of a family drinking low-carbon-footprint orange juice to equal the same family of four flying to Malaga once for their holidays."Beattie also acknowledges the staggering incongruity of platoons of academics flying on carbon-spewing jet aircraft to Mauritius for an environmntal conference. Kevin Anderson seems to have thought that one through a bit farther; see his article Hypocrites in the air: should climate change academics lead by example?.

(idiomatic) To do something pointless or insignificant that will soon be overtaken by events, or that contributes nothing to the solution of a current problem.So even if Beattie isn't putting out the metaphorical house fire very well, he's miles ahead of all his psychological peers who carry on as if the house is not burning.