This book is made of some of my favorite ingredients:

1. It's a book about books and reading: translating, writing, reading, storytelling, listening, even transcribing.

2. It's got all kinds of wordplay about this, particularly a gorgeous, complicated conceit about composition and decomposition -- the sort of thing that reminds me of the happiest and most fantastical lectures I attended while studying early modern English literature.

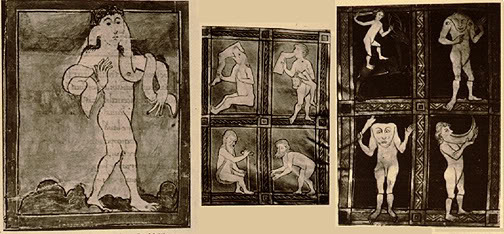

3. Some of the characters are from a recognizable history of the early church -- hooray, I remember learning about this! iconoclasm, the nature of Christ -- it's fun for me to read about fictional characters who are contemporary to these debates.

4. And lastly, it's a whole symphony based on part of the bizarre, self-centered, symbolic, and sometimes very beautiful medieval Christian ideas about far-away places. I haven't properly studied such ideas, but I have just for fun read works such as the Ancren Riwle (that's one way of spelling it!), which is supposed to be a guide book for anchorites who wall themselves up in small spaces in order to live a most holy life, but contains facts such as: the pelican is an allegory for Christ because mother pelicans cut their own breasts in order to feed their young on blood. And I did take a history class on the medieval church, in which I learned how medieval Europeans thought of the Crusades. They believed that the truth of Christianity was evident everywhere, and therefore that any other kind of religion was not what we think of, simply another religion, but a heresy -- deliberate perversion of universal truth. This kind of worldview, which is so simple and so very remote from my own perceptions, fascinates me.

At the beginning of reading The Habitation of the Blessed, the more I realized that it was made up of these things I love, the more I worried that the mixture of these things would disappoint me.

I think it's Tolkien's essay "On Fairy-Stories" that describes the logic of fairyland, which isn't logic at all, but certain causes and effects that happen simply because they must. Too much explanation kills a fairytale. I worried that too much explanation would also kill a blemmye.

But then, a fairytale, or even a whole tree of fairytales, is not a novel. For me to care about a blemmye or a panoti as protagonist, I do need to know and understand her as a person, by some means more than the fairytale "that's how it was."

And particularly, for the story of Prester John, I wanted a very precise balance of explaining well and not explaining too much.

I wanted the motivations of the European Christians to be historically accurate. But I very, very much didn't want the inhabitants of Pentexore to be historically accurate, geographically accurate, or accurate or faithful to anything at all except, to some degree, the imaginations of the medieval Europeans who first sketched them on a map.

Most of all, I did not want Pentexore to be locatable on any modern map. For them to be obviously superimposed on any region of Africa, India, or eastern Asia would maybe have ruined the whole book for me.

Why? Because they're imaginary -- and they're the products of European imagination* (whether Europeans travelling and wildly interpreting things that didn't fit well into their worldview, or Europeans at home and making things up). To most Europeans at home, Prester John or the Antipodes or blemmyae might well have been fairyland.

[* Now that I type this, I'm wondering: how generally true is that? My ideas about these legends are not systematic, but generalized from a few examples, whose context I don't completely grasp. Perhaps the inhabitants of the lands that were the object of these fancies had more agency than I thought in the imagining process. In that case, my reaction to this book might well be quite different...]

I wanted to keep these fancies in fairyland, and not try to accommodate them to real, lived history of actual people in Northern Africa, the Middle East, or Asia during the time of the story. Or much worse, to accommodate these people's history and stories to Prester John... this would be a terrible insult to those people, their history, stories, and descendents, to pretend for the sake of this novel that there was truth in these legends and that the people with their faces on their torsos were in fact medieval Africans or Asians. Or to try to squash legends together, to find something in common between European Christianity's Prester John and a contemporaneous figure from Africa or Asia -- surely that can be done, but who could do it well?

Rather, I wanted Pentexore to be an imaginary land, some place that lives today only as a story, like Atlantis. Or, some place that exists on some maps, but only in a crease: at first you see the familiar world laid out flat, but tug the edges apart again and Pentexore suddenly unfolds. (The title of the sequel, "The Folded World," suggests this -- but I've already peeked inside and I'm worried: instead of the vague and borderless map in The Habitation of the Blessed, The Folded Map has an easily recognized map of the Arabian and Indian peninsulas.)

Anyway, those were my worries but, at least in The Habitation of the Blessed, they were not realized. Unless I missed them, there are no geographical referents that tie Pentexore to a particular region of the real world. I am certain I missed many intertextual references, but I think that Valente did avoid joining the Pentexoreans to any real culture. Of course, to John's bafflement and dismay, they are not Christian. They encountered the Greeks through "Alisaunder," Alexander the Great, but know no Latin at all; the name of the griffin Fortunatus is, apparently, unrelated. Likewise, they don't know "Saracens," which crosses John's mind when he meets a character whose name is Hajji.

So the Pentexoreans are not unhappily superimposed on some real, historical group of people. Valente also, I think, managed a perfect balance between fairyland logic and the needs of a novel; and she satisfied me also as to the accuracy of early Christian characters' concerns.

So, as I realized these things, I was free to relax and enjoy the story: to love Imtithal, to worry about Hagia, to hold myself in reserve as to John and his preconceptions, to absolutely delight (and at the same time hold my breath) in the story of Hiob and the books he plucked from a tree...