What do you think?

Rate this book

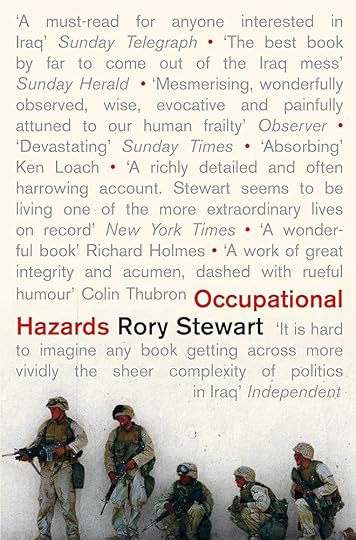

In August 2003, at the age of thirty, Rory Stewart took a taxi from Jordan to Baghdad. A Farsi-speaking British diplomat, he was soon appointed deputy governor of Amarah and then Nasiriyah, provinces in the remote, impoverished marsh regions of southern Iraq. He spent the next eleven months negotiating hostage releases, holding elections, and splicing together some semblance of an infrastructure for a population of millions teetering on the brink of civil war.

The Prince of the Marshes tells the story of Stewart's year. As a participant, he takes us inside the occupation and beyond the Green Zone, introducing us to a colorful cast of Iraqis and revealing the complexity and fragility of a society we struggle to understand. By turns funny and harrowing, moving and incisive, this book amounts to a unique portrait of heroism and the tragedy that intervention inevitably courts in the modern age.

448 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 2005

We were surrounded by half-forgotten history. I had met some people back home who still remembered British political officers who served in Iraq between 1916 and 1958. [...]

Our position reminded people of colonialism. But we were not colonial officers. Colonial officers in British India served for forty years, spoke the local languages fluently, and risked their lives and health, administering justice and collecting revenue in tiny, isolated districts, protected only by a small local levy. They often ruled indirectly, 'advising' local kings, tolerating the flaws in their administration and toppling them only if they seriously damaged the security of the state. They put a strong emphasis on local knowledge, courage, initiative, and probity, but they were ruthless in controlling dissent and wary of political change.

By contrast, our governments, like the United Nations, kept us on short contracts and prevented us from going into dangerous or isolated areas. They gave us little time or incentive to develop serious local expertise, and they considered indirect rule through local elites unacceptable. They had no long-term commitment to ruling the country. Their aim was to transfer power to an elected Iraqi government.

It appeared from all of this [powerpoint presentation] that we were being told that within the next seven months we should, among many other things, elect a transitional assembly, privatise state-owned enterprises, install electronic trading on the Baghdad stock exchange, reform the university curriculum, generate six thousand megawatts of electrical power, vet all the judges, and have thirty-two thousand Iraqi soldiers selected and trained in the new Civil Defence Corps and ensure that 90 per cent of Iraqis received terrestrial television broadcasts.

[...]

There was a silence and then a general said, "I'm sorry. Did I misunderstand you? Did you just say that you have briefed this plan to the highest levels in Washington without consulting any one of us around this table?"

Bremer cut in. "General, there has been an extensive consultation process - parts of this plan have been shown to people all over Iraq - all the relevant departments have been canvassed."

"Well, I sure as hell know that I haven't seen it," said the general. "Has anyone else seen it in this room? Any of my military colleagues?" Heads shook. "Any of the governors?" We civilians shook our heads. "You don't think you could have shown it to some of us?"

"We are showing it to you now."

It was ten months since the looting in Baghdad had badly damaged the reputation of the Coalition - a disaster that most commentators blamed on poor planning, insufficient troops, and bad command. In Amara, however, where we had planned, had months to prepare, and had many soldiers, well trained and experienced in crowd control from Northern Ireland, looting had occurred again partly because we thought property less important than life. And because we could not define the conditions under which we were prepared to kill Iraqis or have our own soldiers killed. Occupation is not a science but a deep art, which can only be learned through experience.

Finally, the governor came to the point. "And why did your soldiers not protect this building from the crowd? You send home my security force, dissolved the police line, and took responsibility for the building. How did you then let the crowd get in and steal everything?"

One of us replied, "Governor, maybe it is better that a little computer equipment gets stolen than that more people get killed."

And he then said, "What are you talking about? Would you let the mob go stampeding into your office and loot your computer equipment?" We had no answer. Of course, we would have shot anyone who tried to break into our compound. The governor left that meeting certain that we were not prepared to give him the level of protection we gave ourselves. And from then onwards any hope of co-operation was lost.

Nowhere in thirty years has there been such a concentration of foreign money, manpower, and determination as in in Iraq. Nowhere has their failure been more dramatic. And yet few convincing explanations of the mess have emerged, and no attractive solutions. Some things are now clear. Iraqis are the only people who can rebuild their nation. We cannot. We have done what good we can do. It is not our tactics but the very fact of our presence that is inflaming the situation. We cannot improve the situation because our institutions are fundamentally unsuited to nation-building: we do not have the personnel, the training, or the political culture to do it, nor the sympathy for local politics. We are too unpopular to be able to defeat the insurgency, stop a civil war, or create security. You cannot predict which policy will work but you must recognise when your policy has failed. In short, I can confidently assert that Iraqis are the only people with the moral authority, understanding, and skills to rebuild their nation. Beyond that I, like almost everyone else, would be guessing.