Problems in the Reception of Christine Brooke-Rose, and Why I Won't be Reading More of Her Work

-

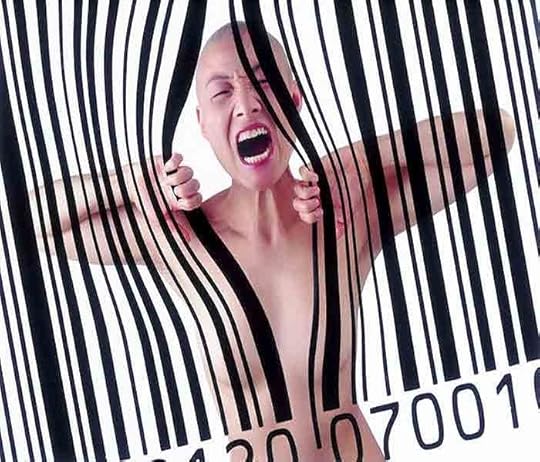

The received idea about Brooke Rose is that she struggled for visibility during her lifetime, but is now recognized as one of the most important experimental novelists of the second half of the twentieth century. That idea—repeated in blogs and reviews—comes mainly from critics' awareness of several scholars working in the 1990s, beginning with four women scholars: Susan Hawkins ("Innovation/History/Politics: Reading Christine Brooke-Rose's Amalgamemnon, 1991), Sarah Birch (Christine Brooke-Rose and Contemporary Fiction, 1994), Judy Little (The Experimental Self, 1996), and Karen Lawrence (Techniques of Living: Fiction and Theory in the Work of Christine Brooke-Rose). It's possible the reception, which continues to grow, can be divided into critics who are interested in Brooke-Rose's implementation of postmodern theory, and those who read her work as a record of the world of late-capitalist spectacle and diminishing literacy. I'll call these the first and second readings of her work.

At the extreme, the first would compare her with books like Derrida's Glas, which is an attempt to assemble a book out of what Derrida called "literature" and "philosophy." (See for example Marija Grech, "Re-Visions of the End: Christine Brooke-Rose and the Post-Literary Author(s)," Journal of Modern Literature, 2021.)

The second reading would compare Brook-Rose with other chroniclers of contemporary disaffection and alienation, such as the Don DeLillo of White Noise. (See for example Brian McHale's essay in Utterly Other Discourse, Dalkey, 1995.)

It's tricky to write a novel hoping it will embody a particular theory. Iris Murdoch was convincing on that point and aware of the shortfalls of the "philosophical novel." That doesn't mean there aren't interesting things to be said about how literature engages philosophy, as Lawrence's book shows. But the fascination of watching theory emerge from fiction, or embody itself in fiction, or speak as fiction, or become identical with fiction, doesn't correlate with the pleasures of attending to what is happening in the text. Derrida's Glas has a remarkably distant implied author, and that makes it an exceptionally cold text—a phenomenon that's not immediately connected to the many propositions it implies about coherence, "philosophy," and "literature." At the same time, it can be rewarding to read fiction as a sign of its social context, but it's not the same as reading what the text itself says. DeLillo is full of strange silences and oddly woven transitions that have little to do with how his work looks as a barometer of postmodern alienation.

I would like to propose a different reading of Amalgamemnon. I take my cue from Lawrence's observation that Brooke-Rose "explores opportunities to convert pain, through discipline, into fictional power." Pain—the narrator's, the implied author's, and in the end the reader's—comes in part from the difficult relation between the implied author's interest in theory (the first reading) and in part from the awareness that the narrator's life and values (as a classicist and expert in literature) are being swept away by capitalism, "hitech," "textermination," and general ignorance (the second reading). But most of the pain in Amalgamemnon comes directly from the narrator's horrible relation to her partner.

As Susan Hawkins observes, the the sexual dynamics of the narrator(s) and her partner(s) can be understood as a parody or criticism of "the Western obsesson with binarism and gendered voice" (that would be the first reading, and, in a feminist inflection, the second), but Brooke-Rose "never projects... anything close to a future of sexual equality" (p. 69). To me, that's so much understated that it's nearly evasive. The "sexual discourse" is desperately, hopelessly unhappy.

Early on there's a sex scene that takes place, apparently, during a half-page gap between paragraphs. When the text returns we have this:

"Soon he will come. There will occur mimecstacy even if millions of human cells remain unconvinced and race around all night on their multiplex business, transmitting coded information, most of it lost forever" (p. 15)

"Mimecstacy" is the narrator's acid word for feigned pleasure, in this case faked orgasm. The prefix mim- is attached to many words to indicate that she's pretending. She often "mimagrees" with her partner. The passag continues:

"Soon he will snore, in a stentorian sleep, a foreign body in bed. There will occur the blanket bodily transfer to the livingroom for a night of utterly other discourses that will crackle out of disturbances in the ionosphere into a minicircus of light upon a stage of say Herodotus and generate endless stepping-stones into the dark, the Phoenician kidnapping Io and the Greeks in Colchis carrying off the king's daughter Medea...

Tomorrow at breakfast Willy will pleased as punch bring out as the fruit of deep reflection the non-creativity of women look at music painting sculpture in history and I shall put on my postface and mimagree, unless I put on my preface and go through the routine of certain social factors such as disparagement from birth the lack of expectation not to mention facilities a womb of one's own a womb with a view an enormous womb and he won't like the countertone of it all, unless his eyes will be sexclaiming still what fun, it'll talk if you wind it up, as if disputation were proof of my commitment."

That is astonishingly difficult to read: the hatred builds up from the lack of sexual pleasure to the exile into the livingroom, and from there to the mansplaining at breakfast and her option to pretend to agree, and from there to the sarcastic puns on women's possibilities, on to the possibility that Willy will like what she says if he sees sex in it, and his way of thinking of her as an "it" that's there for "fun."

There are many passages like this. The hatred of the partner and the relationship is poisoned by the necessary castling: she keeps most of her classics learning to herself, but hatred would become self-hatred if she didn't pause occasionally in her "mimagreeing" to put on a hopeless defense. There are some especially vile exercises in self-effacing complicity on pp. 25, 45, and 140. I do not object to reports from a poisoned well of experience. What makes these especially challenging is that, in accord with the book's theme of repetition and redundancy (the narrator has been fired from her job as classicist), they keep coming back. Right at the end of the book there's this:

"Soon he will come. Soon he will sleep and snore, a foreign body in bed. There will occur the blanket bodily transfer to the livingroom for a night of utterly other discourses that will spark out of a minicircus of light upon a page of say Lucretius and generate endless sepping-stones into the dark...

Tomorrow at breakfast he will talk of this and that and then we shall walk down the street to the Job-Centre as usual." (p. 143)

In this final iteration, "this and that" stands for the painful exchange the narrator described in the first iteration. Nothing has changed except the narrator's need to explain that one possibility.

This is excruciating, unlike the apparently rewarding repetitions of November 18 in Solvej Balle's seven-volume On the Calculation of Volume or the harmless whimsy of Danny Rubin and Harold Ramis's "Groundhog Day." It can't be adequately understood as an example of postmodern theorizations of unoriginality and redundancy (the first reading) or feminist protest (the second reading).

For me the limit of reading Brooke-Rose, and the reason I will not be returning to her, is that she is not, in the end, mainly writing theory into fiction (the first reading) or bearing witness to contemporary dysphoria (the second reading). She is repeating, in the way Freud first described it, an unresolved trauma, and we are the witnesses. The authorial voice is in control of the individual passages but not the larger frame. Reading Brook-Rose I feel like a consulting psychiatrist, witnessing an endless display of trauma. It can be compelling, and it is seldom less than deeply affecting, but in the end all I can do is leave.