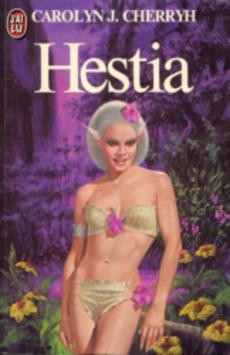

This book is a really obvious allegory of the settling of America, except that this time the natives are a race of primitive cat-people. (Which is fairly problematic, when you think about it, given all the times that settlers referred to Native Americans as being less than human.) Cherryh really goes out of her way to underscore the resemblance, giving the settlers all the characteristics — forms of dress, clothing, and language, not to mention being white with English surnames — that are traditionally associated with Americans pushing West in the 19th century, even though the book is set in a far-future universe with spaceflight between planets, one of many aspects of the book that don’t quite make sense. I can accept that a low-priority colony planet might operate at a lower technology level than the planets that build the spaceships. It seems less likely, though, that an engineer trained on one of those planets would know anything about building dams without the use of robots and lasers and all the fancy advanced technology that such a world must have to do its engineering. The spaceships can’t be the only sign of high technology there is, can they? Furthermore, it makes even less sense that the mother planet would bother sending a single person to a low-priority colony. (Ok, there were two — one has second thoughts and skedaddles, leaving our hero behind, partly because he was arrested by the colonials in case he started getting second thoughts, too — but still.) Either they would send a team with a large quantity of equipment, or they would send some books on dam-building and a note saying “good luck”. Finally, of course, there’s the whole question of inter-species romance, as signaled by the cover illustration of a cat-woman wearing a bikini: unfortunately, Cherryh puts about the same amount of thought into it as a B-movie scriptwriter. (For once, the cover illustrators of a 70’s sci-fi or fantasy paperback have given a female character more clothes than she usually wears: Sazhje, being, as mentioned, one of a race of primitive cat-people, generally wears nothing at all.) The most annoying part of the book, though, is the way it distributes the blame for imperialism. The settlers are often small-minded, violent and xenophobic, prejudiced not just against the cat-people but also against other humans not from Hestia and even native-born Hestians who have off-worlder parents: our hero, by contrast, is enlightened and broad-minded. Of course, our hero also represents the imperial center, the people who are responsible for dropping the settlers on Hestia and creating the conflict with the cat-people: to absolve them of any blame is to miss the point by a considerable margin. One could perhaps overlook these political issues if the book were better, but it’s really pretty predictable: Cherryh is good at maintaining tension, but there’s only so much you can do with a by-the-numbers plot. Definitely the worst of my continuing review of early Cherryh so far.