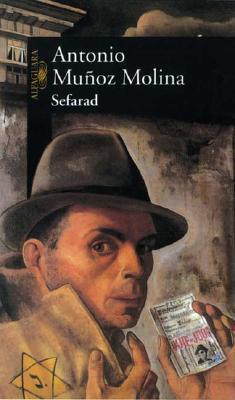

What do you think?

Rate this book

608 pages

First published March 7, 2001

It’s true, many of us would like to live in the immutable past of our memories, a past that seems to live on in the taste of some foods and those dates marked in red on the calendars…

The great night of Europe is shot through with long, sinister trains, with convoys of cattle and freight cars with boarded-up windows moving very slowly toward barren, wintry, snow- or mud-covered expanses encircled by barbed wire and guard towers.

Love, suffering, even some of the greatest hells on Earth are erased after one or two generations, and a day comes when there is not one living witness who can remember.