What do you think?

Rate this book

384 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 2009

Suddenly Lord Marchmain moved his hand to his forehead; I thought he had felt the touch of the chrism and was wiping it away. “O God,” I prayed, “don’t let him do that.” But there was no need for fear; the hand moved slowly down his breast, then to his shoulder, and Lord Marchmain made the sign of the cross. Then I knew that the sign I had asked for was not a little thing, not a passing nod of recognition, and a phrase came to me back from my childhood of the veil of the temple being rent from top to bottom.Consider the scene where Charles gives up Julia, understanding why she has to leave him:

“I don’t want to make it easier for you,” I said; “I hope your heart may break; but I do understand.”Consider also his conversion, his prayer in the chapel:

The chapel showed no ill-effects of its long neglect; the art-nouveau paint was as fresh and bright, as ever; the art-nouveau lamp burned once more before the altar. I said a prayer, an ancient newly learned form of words, and left, turning towards the camp...And if the text of the book itself doesn't convince you, read this book. Or maybe don't: you might want to cling on to your own reading of Brideshead Revisited instead.

...

Something quite remote from anything the builders intended has come out of their work, and out of the fierce little human tragedy in which I played; something none of us thought about at the time: a small red flame--a beaten-copper lamp of deplorable design, relit before the beaten-copper doors of a tabernacle; the flame which the old knights saw from their tombs, which they saw put out; that flame burns again for other soldiers, far from home, farther, in heart, than Acre or Jerusalem. It could not have been lit but for the builders and the tragedians, and there I found it this morning, burning anew among the old stones.

I quickened my pace and reached the hut which served us for our ante-room.

“You’re looking unusually cheerful to-day,” said the second in-command.

Since its publication in 1945, a vast amount has been written about the novel and about the striking similarities between two families, the fictional Flytes and the real-life Lygons. The parallels seem almost infinite--between Lord Beauchamp and Lord Marchmain, Hugh Lygon and Sebastian, and the two great houses, magnificent Brideshead and Madresfield, the Lygons' moated manor house in Worcestershire

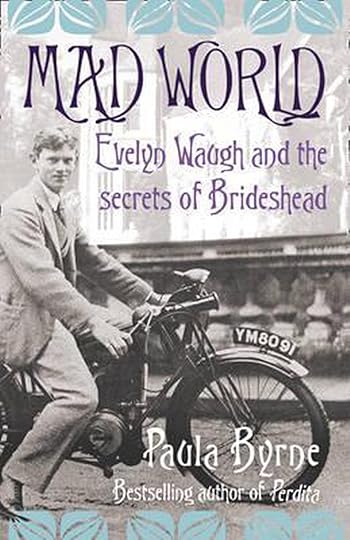

Paula Byrne is the latest to explore the people and the story that inspired the book and she does so with acuity and panache. Her stated aim is to portray Waugh through his friendship with the Lygons, and in the process reveal some substantial new information about the high-society scandal that in 1931 electrified the country.

...

Byrne understands very well the powerful enchantment that Madresfield, or "Mad" as the girls called it, cast over Waugh. The beauty of the place, the limit-less freedom, the traditions of centuries juxtaposed with childish high spirits and silliness, all proved irresistible to the penniless young man from Golders Green. Byrne entertainingly summarises his career up to this point--the childhood, the schooldays, the melancholia and debauchery of Oxford, the schoolmastering and the first published works--and layers in with this the story of the Lygons, of Lord Beauchamp's early life, and of those of his wife and children.

...

Essentially, what Mad World provides is a lively introduction to Waugh and to Brideshead, and to the rarefied social world in which much of the novel is set. To this is added a small amount of new material, to which, understandably, much emphasis is given.

...

Much as I admire Mad World, I do have some reservations: source notes, disgracefully, are almost non-existent and the index is virtually useless.

...