What do you think?

Rate this book

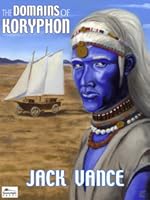

224 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 1974

"Except for a few special cases, title to every parcel of real property derives from an act of violence, more or less remote, and ownership is only as valid as the strength and will required to maintain it. This is the lesson of history, whether you like it or not.”Well, okay then.

“The mourning of defeated peoples, while pathetic and tragic, is usually futile,” said Kelse.

Erris Sammatzen approached Jemasze. “And this is Uther Madduc’s ‘wonderful joke’?”Indeed.

“So I believe.”

“But what’s so funny?”

“The magnificent ability of the human race to delude itself.”

“That’s bathos, not humor,” said Sammatzen shortly.

Jack Vance’s The Gray Prince bothers the hell out of me. It has an excellent theme, with a tomato-surprise ending that defies guessing, and involves some moral questions that are more and more relevant these days. But you have to wade through some god-awful stuff to get there.

The writing style is of a pedantic, top-heavy sort which the dust-jacket calls “evocative” and I call Byzantine — it kept me thumbing my dictionary and increased my vocabulary immensely, but it didn’t arouse my interest: even the fight scenes were stately. I pressed on, and discovered that there seem to be four or five protagonists, with whom Vance plays Musical Viewpoints at random and without warning — and none of them is The Grey Prince, who turns out to be a very minor character and a humbug in the bargain. Finally, I was horribly annoyed by Vance’s heavy use of footnotes to explain plot essentials rather than working them into the story [footnote: actually I just hate footnotes on principle.] — and worse, by the fact that non-essential footnotes often held more potential interest than the text, and were invariably abandoned. When the interruptions are more interesting than the matter at hand, something is badly wrong.

All in all, Prince reads like a history professor’s dry and academic account of what one can dimly see must have been a rousing era. But if you read only the prologue and the last two chapters, you’ll find some thoughtful and stimulating moral philosophy. It’s the middle hundred and sixty-four pages that hung me up.

The space age is thirty thousand years old. Men have moved from star to star in search of wealth and glory; the Gaean Reach encompasses a perceptible fraction of the galaxy. Trade routes thread space like capillaries in living tissue; thousands of worlds have been colonized, each different from every other, each working its specific change upon those men who live there. Never has the human race been less homogeneous. (p. 5)