What do you think?

Rate this book

144 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 2003

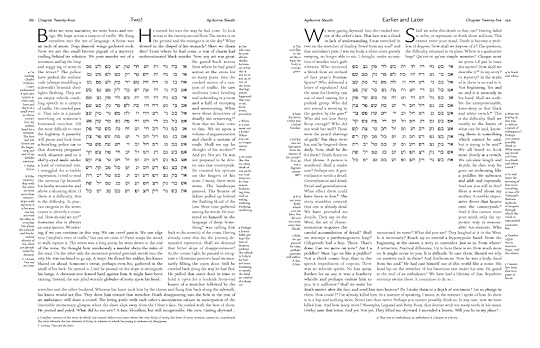

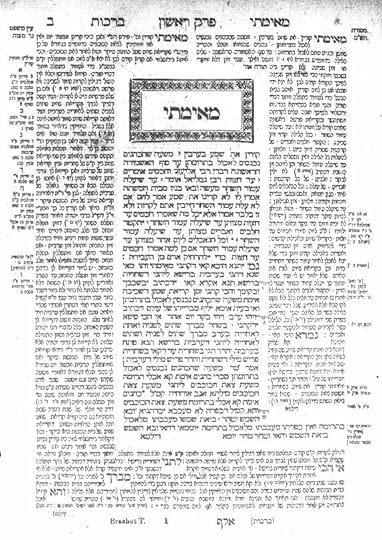

We sleuth, we sleuth, yet meaning escapes us.One could be forgiven for being a bit overwhelmed by this book upon first glance. There is, at a purely textual level, a lot going on here. Most pages look like this:

Those of us who say the Torah is not from heaven. Those of us who interpret the word of the Torah in a way contrary to the halakhah. Those of us who profane the covenant inscribed in the flesh. Those of us who profane the holiness of the sacrifices. Those of us who disdain the half-holidays. Those of us who say the whole Torah comes from heaven, except this deduction, except this exception, except this a fortiori, or this proof by analogy. Those of us who have the opportunity to study the Torah and do not do so. Those of us who study the Torah, but only from time to time. Those of us who cause the face of their fellow to pale with shame. All these have no share in the World to Come: even if they know the Torah and have performed charitable deeds, all these have no share in the World to Come.The quote provided comes from a Baraita ("external" or "outside" - refers to teachings "outside" of the six orders of the Mishnah. Originally, "Baraita" probably referred to teachings from schools outside of the main Mishnaic-era academies). While on the one hand an Apikoros can be boiled down to a form of "heretic", Majzels himself prefers "lapsed Jew" - either way, it is an individual who is outside of the faith. They are Other. The concept of Other is continually revisited throughout the text – and the extensive quotes from Derrida, Levinas, Jabès, Lyotard, etc ground this work pretty firmly in a post-structural framework. Additionally, it is intentional - viewed in the context of the rest of the text - that Majzels chooses to define the outsider with an outsider text. The book is filled with these small repetitions – flourishes really – where Majzels underlines and draws attention to the craftsmanship and detail of the work.

Antoninus said to Rebbi: The body and the soul have an alibi to free themselves from punishment on the Judgment Day. How so? The body can claim, “The soul is the one that sinned. From the time it left me, I have been lying silent like a rock in the grave.” And the soul can say, “It is the body that has sinned. From the day that I left it I have been flying in the air like a bird.” Rebbi answered, “Allow me to offer a parable. To what can this be compared? To a king who had a beautiful orchard that contained luscious figs and he posted in it two guards, one lame and the other blind. Said the lame one to the blind one, “I see luscious fruits in the orchard. Come, put me on your shoulders, and together we will pick the figs and eat them.” The lame one climbed on the blind one’s back, and they picked the figs and ate them. A while later the king, the owner of the orchard found that his figs were gone.I highlight this for three reasons.

He said to the guards, “What happened to my luscious figs?” Said the lame one, “Do I have feet to take me to the fig trees?” Said the blind one, “Do I have eyes to see where the figs are?” What did the owner do? He placed the lame one on the shoulders of the blind one, and judged them together. So too, on the Day of Judgment, the Holy One Blessed Be He, brings the soul and puts it back into the body and judges them jointly.

(/ænəkəˈluːθɒn/ an-ə-kə-loo-thon; from the Greek, anakolouthon, from an-: 'not' + akolouthos: 'following') is a rhetorical device that can be defined as wording ignoring syntax. This is achieved by transposing clauses. Anacoluthon often contains a sentence interrupted halfway. The sentence then has a change in form.You’ll know what I mean.

But we were asking: which sin must a sleuth, if he is to sleuth, avoid? Digression.Just so we’re clear, in the context of the book, that’s a joke (and a funny one at that).

I considered my silent options silently. I weighed those options on a subatomic scale and found them wanting. Wanting what? Wanting more. Options. Booger wanted a spoken promise of silence. I considered speaking out against silence. To refuse silence is well and good, but would speaking retrieve a body by the gate or a dentist with too many teeth in his name? I considered the possibility of a silent refusal of silence. I mean, to remain silent in the face of Booger’s demand for my silence. But silence left too much unsaid. Clearly (it seemed so at the time), Booger (Mr. Rooney to you) and his shadowy shadow both preferred speech, I mean mine, to silence. They required a sentence. Silence (in the face of their demand for my silence) might lead to a sentence of death. Possibly. Here, another option: to speak a sentence of silent acquiescence. But if I spoke my silence now, would I not be acquiescing to murder? If I played mute to Booger’s tune, who would satisfy suspicion’s passing glance from the head of a uniform, that eye-to-eye with the man whose shoulder itched to press shoulder-to-shoulder with that sketch artist (he had by now already done so)? Silence was an option that slid on the buttery slope of my tongue.Oh, yes, there is a character called Booger. This book doesn't actually take itself as seriously as it appears on the surface. Scatological and urinary jokes and discussions abound. There are many plays with the name Booger (most utilizing some emphasis on the word “pick”). Snickering penis allusions are rampant as well. That’s not to say that childish humor is all there is – it shows up, more frequent than you would expect, but really only to continue to reinforce the levity of the text. They pretty much act as moments of intermission, where the author is still telling the reader to relax – it’s not all heavy lifting here.