What do you think?

Rate this book

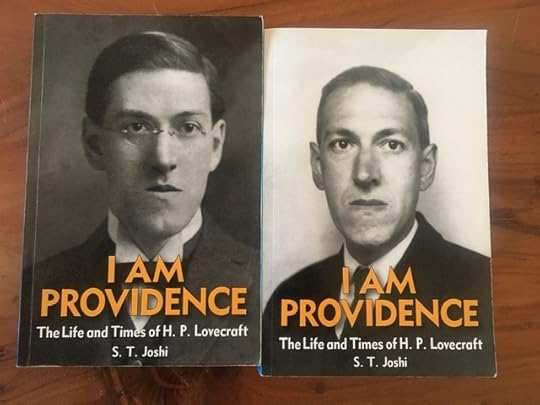

1148 pages, Hardcover

First published August 20, 2010

Lovecraft is an oddity—neither he nor his work is “normal” in any conventional sense, and much of the fascination that continues to surround him resides exactly in this fact. But both his supporters and his detractors would do well to examine the facts about both his life and his work, and also the perspective from which they make their own pronouncements and evaluations of his character. He was a human being like any of us—neither a lunatic nor a superman. He had his share of flaws and virtues. But he is dead now, and no amount of praise or blame will have any effect upon the course of his life. His work alone remains. (p. 1451).

No change of faith can dull the colours and magic of spring, or dampen the native exuberance of perfect health; and the consolations of taste and intellect are infinite. It is easy to remove the mind from harping on the lost illusion of immortality. The disciplined mind fears nothing and craves no sugar-plum at the day’s end, but is content to accept life and serve society as best it may. Personally I should not care for immortality in the least. There is nothing better than oblivion, since in oblivion there is no wish unfulfilled. We had it before we were born, yet did not complain. Shall we then whine because we know it will return? It is Elysium enough for me, at any rate. (p. 469).

It becomes clear from this passage that the principal cause, in the atheist Lovecraft’s mind, of the Puritans’ ills was their religion . In discussing “The Picture in the House” with Robert E. Howard in 1930, he remarks: “Bunch together a group of people deliberately chosen for strong religious feelings, and you have a practical guarantee of dark morbidities expressed in crime, perversion, and insanity.” (p. 532).

I’d say that good art means the ability of any one man to pin down in some permanent and intelligible medium a sort of idea of what he sees in Nature that nobody else sees. In other words, to make the other fellow grasp, through skilled selective care in interpretative reproduction or symbolism, some inkling of what only the artist himself could possibly see in the actual objective scene itself. (p. 592).

I could not write about “ordinary people” because I am not in the least interested in them. Without interest there can be no art. Man’s relations to man do not captivate my fancy. It is man’s relation to the cosmos—to the unknown—which alone arouses in me the spark of creative imagination. The humanocentric pose is impossible to me, for I cannot acquire the primitive myopia which magnifies the earth and ignores the background.

To all intents & purposes I am more naturally isolated from mankind than Nathaniel Hawthorne himself, who dwelt alone in the midst of crowds, & whom Salem knew only after he died. Therefore, it may be taken as axiomatic that the people of a place matter absolutely nothing to me except as components of the general landscape & scenery. . . . My life lies not among people but among scenes—my local affections are not personal, but topographical & architectural. . . . I am always an outsider—to all scenes & all people—but outsiders have their sentimental preferences in visual environment. I will be dogmatic only to the extent of saying that it is New England I must have—in some form or other. Providence is part of me—I am Providence . . . Providence is my home, & there I shall end my days if I can do so with any semblance of peace, dignity, or appropriateness… (pp. 832-833).

all my tales are based on the fundamental premise that common human laws and interests and emotions have no validity or significance in the vast cosmos-at-large. To me there is nothing but puerility in a tale in which the human form—and the local human passions and conditions and standards—are depicted as native to other worlds or other universes. To achieve the essence of real externality, whether of time or space or dimension, one must forget that such things as organic life, good and evil, love and hate, and all such local attributes of a negligible and temporary race called mankind, have any existence at all. (p. 860)

Early the following Tuesday morning, before I had gone to work, Howard arrived back from Quebec. I have never before nor since seen such a sight. Folds of skin hanging from a skeleton. Eyes sunk in sockets like burnt holes in a blanket. Those delicate, sensitive artist’s hands and fingers nothing but claws. The man was dead except for his nerves, on which he was functioning. . . . I was scared. Because I was scared I was angry. Possibly my anger was largely at myself for letting him go alone on that trip. But whatever its real cause, it was genuine anger that I took out on him. He needed a brake; well, he’d have the brake applied right now.

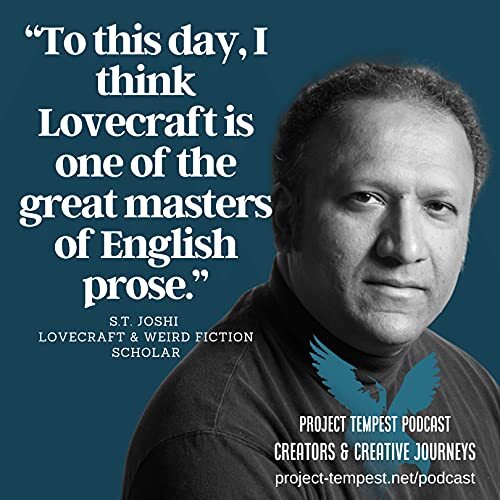

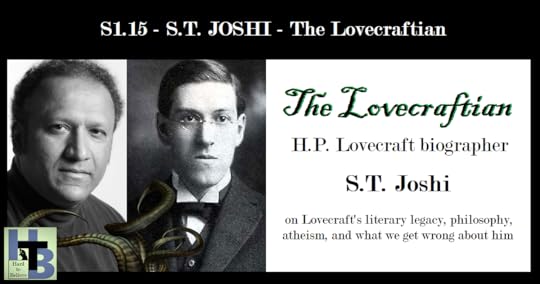

S. T. Joshi has created what I find to be the definitive biography of Howard Phillips Lovecraft. It must have been a true labor of love for Joshi.

There are two things, unfortunately, that will deter many people from picking this book up and giving it a read:

This is sad. H. P. Lovecraft was an extremely interesting man. Sure, he had his faults, as we all do. He is definitely on my list of authors with whom I would love to spend an evening by a fire in some cozy den discussing many things.

This book has truly increased my knowledge of Lovecraft, but it has also brought me closer to the man. You cannot absorb this much about a person without beginning to feel that you actually knew them. My esteem for H. P. Lovecraft has most definitely surged.

I'm also extremely impressed with S. T. Joshi, the author of this work. I cannot even begin to imagine the years of toil that were involved in researching for this project. It was worth it, though. Joshi has managed to humanize Lovecraft. He doesn't hide the ugliness, but attempts to explain it a bit; understanding assists in developing a less biased opinion of a subject.

I would most assuredly recommend a reading of Joshi's book for anyone with the slightest interest or curiousity regarding its subject.. Howard Phillips Lovecraft, his philosophies, his struggles, his likes and dislikes, his life. If life had thrown just a few less curve balls at Howard, one may wonder just how far and how successful he may have been; particularly if he had kept his health and lasted into his 70s or 80s. Instead, he was lost to us way too soon (46 years old), just as one of his inspirational mentors, E. A. Poe. (died at 40).

Howard never attained any commercial success in his lifetime. He never had a published book of any of his works while still living. His stories were mostly disseminated via amateur presses or magazines, such as Weird Tales.

There is a decent biographical article in Wikipedia regarding Lovecraft that may stir your interest toward the full story found in Joshi's biography on Lovecraft. I hope you give it a go someday.