What do you think?

Rate this book

128 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 1988

A long series of tiny shocks,While it has some compelling moments, such as its concluding discussion of Albrecht Altdorfer's's extraordinary painting The Battle of Alexander at Issus, whose vast vista the narrator is taught to construe as a prophecy of conquest and colonialism—

from the first and the second pasts,

not translated into the spoken

language of the present, they

remain a broken corpus guarded

by Fungisi and the wolf's shadow.

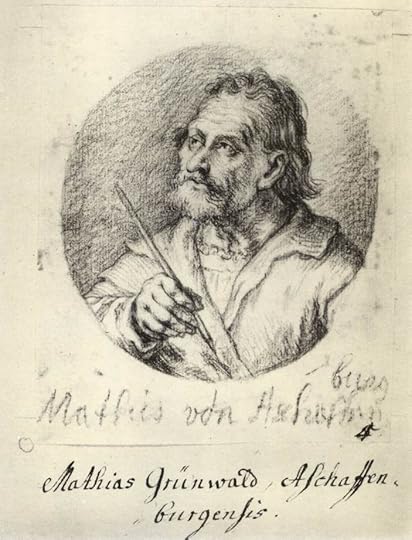

As fortunate,—I much prefer the first two parts, both narrated in the third person to create fragmentary portraits of Grünewald and Steller.

did the clever chaplain, who

had hung up an oleograph

of the battle scene beside

the blackboard describe the outcome

of this affair. It was,

he said, a demonstration

of the necessary destruction of all

the hordes coming up from the East.

and thus a contribution to the history

of salvation.

To him the painter, this is creation,In the background is the failed revolution of Thomas Müntzer and the first stirrings of German fascism. Grünewald, the poet tells us, "must have tended / towards an extremist view of the world" and "will have come to see the redemption of the / living as one from life itself."

image of our insane presence

on the surface of the earth,

the regeneration proceeding

in downward orbits

whose parasitical shapes

intertwine, and, growing into

and out of one another, surge

as a demonic swarm

into the hermit’s quietude.

perscrutamini scripturas,Whatever precursors in German literature Sebald is calling upon are alas lost on me, but in the troubled northern expedition I heard echoes of The Rime of the Ancient Mariner and Frankenstein and Moby-Dick, which is generally in keeping with Sebald's brand of rueful "after Auschwitz" neo-Romanticism. This section evokes everything from St. Petersburg (perhaps recalling Pushkin’s "Bronze Horseman")—

shouldn’t that read,

perscrutamini naturas rerum?

Kronstadt, Oranienbaum, Peterhof—to an illicit handjob—

and last in the Torricellian void,

a thirty-four-year-old bastard,

marooned on the Neva’s marsh delta,

St. Petersburg under the fortress,

the new Russian capital,

uncanny to a stranger,

no more than a chaos erupting,

buildings that began to subside

as soon as erected, and nowhere

a vista quite straight.

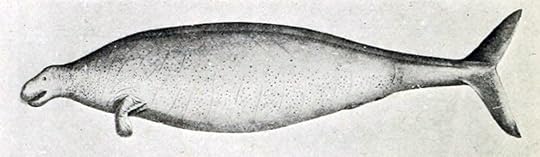

He spends the whole summer—suggesting, as a first book ought to do, all the different writers the writer might have become.

bent over the jumble of cards,

while the naturalist’s neglected

wife, gaudily dressed, sits

beside him and with her split

fin strokes the glans that throbs

like his heart. Steller feels science

shrinking to a single slightly

painful point. On the other hand

the foam bubbles, to him, are

a paradigm. Come, he whispers

into her ear in his desperation,

come with me to Siberia as

my true wife, and already hears

the answer: wherever

you go I will

go with you.

For an adult reader, the possible verdicts are five: I can see this is good and I like it; I can see this is good but I don't like it; I can see this is good and, though at present I don't like it, I believe that with perseverance I shall come to like it; I can see that this is trash but I like it; I can see that this is trash and I don't like it.Sebald has moved from the second to the third category for me, and will perhaps be arriving at the first any day now. I look forward to the two books of his that I have not yet read, The Emigrants and Vertigo.

ignara d’equilibri,

che cieca compie, l’uno dopo l’altro,

esperimenti privi di costrutto

e, come insano bricoleur, ecco

distrugge quanto appena ha creato.

Sperimentare fino al limite postremo,

è l’unico suo scopo, germinare,

perpetuarsi e riprodursi,

anche in noi e attraverso di noi, e mediante

i congegni nati dalle nostre menti,

in un’unica accozzaglia,

lavora inesausto su tracce,

ancorché labili, di auto-organizzazione,

e talvolta ne risulta

un ordine, a tratti bello

e rappacificante, ma anche più crudele

del tempo passato, il tempo dell’ignoranza

più avanti afferma che

Le linee guida dei grandi

sistemi non si possono

armonizzare, troppo diffuso è l’atto

della violenza, ogni cosa sempre

l’inizio dell’altra

e viceversa.

to him, the painter, this is creation,sebald’s posthumously published first book, after nature (nach der natur) is comprised of three long poems considering the human relationship to our natural world, conveyed through the lives of three german figures: painter matthias grünewald, naturalist georg steller, and the author himself. incubating themes that would be more fully fleshed out in his later works, after nature is a beautifully composed and thoughtful rumination on time, place, setting, and the world around us.

image of our insane presence

on the surface of the earth,

the regeneration proceeding

in downward orbits

whose parasitical shapes

intertwine, and, growing into

and out of one another, surge

as a demonic swarm

into the hermit’s quietude.