What do you think?

Rate this book

165 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 2007

Uh-oh! First person alert. The beginning was contrived which took some stern resolve to wade through; from that moment on Raj was slotted into dodgy narrator pigeon-hole. A quick read that had its moments, yet not to be recommended.

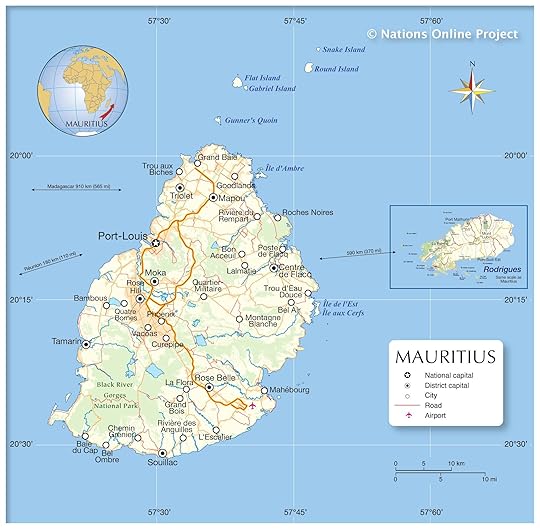

Uh-oh! First person alert. The beginning was contrived which took some stern resolve to wade through; from that moment on Raj was slotted into dodgy narrator pigeon-hole. A quick read that had its moments, yet not to be recommended.“You say you are an orphan, or a widow or a widower, but when you have lost two sons on the same day, two brothers on the same day, what are you? What word is there to say what you have become?”Even though the blurb sounded interesting enough (I mean, I totally didn't know that in 1940 a cargo of Jews was denied entry into Palestine and then sent to Mauritius where they were forced to stay in jail for months, like ... what?), this isn't a book that I would normally pick up because I'm not the biggest fan of historical fiction and I also haven't read a proper coming-of-age tale in a while. But ... I'm happy to report that this book exceeded my expectations, heck, it even managed to make me cry.

“The French words we used were foreign to both of us, from now on it was a language we had to bend to what was in our own minds, to what we wanted to say, no longer, as it was at school, simply decoding and repeating.”Raj’s own personal sense of heartache and grief, his own deep well of loneliness, all of these emotions that overwhelm him after the loss of his two brothers in an apocalyptic storm, are qualities that he recognizes immediately in the eyes of David. Who is this ghost-like white child, with blond curly hair and the skinny body of a stick figure? And why is he so sad and alone as well? For the most part, it is an unspoken bond that develops between the two—a companionship of gestures, looks, and broken phrases in a smattering of French and Yiddish.

“Knowing that regrets serve no purpose, that you need a lot of luck to fulfill your dreams, that the best way to live is to do your utmost at every moment and that so many things will happen without us, even though we spend all out time scurrying like madmen, in the belief that we can make some difference.”The Last Brother is a unique tale (that truly has never been told before) that explores a lesser-known corner of World War II history through the lens of fiction. Moving back and forth between two timelines (9-year-old and 70-year-old Raj), Nathacha Appanah manages to capture the essence of this tormented life, all his regrets, guilt and shame, suppression, losses, displacements. It's a truly depressing read, for sure, but also a necessary one. Nathacha through the help of dream sequences and memory, forces Raj as an old man to reconsider the events that marked him, that shaped him into being the man he eventually became.

“But who am I to be telling all this today, to be saying all this, to be talking about him like this, as if I had some kind of right to speak of these appalling things. What do I know of how he might have felt, what do I know of deportation and pogroms, what do I know of prison?”Appanah asks the hard question of whose story this really is, of who is allowed to speak, and for whom? and in what capacity? Of what should be done when the person whose story this is is dead and can no longer speak for themselves?