What do you think?

Rate this book

187 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 1973

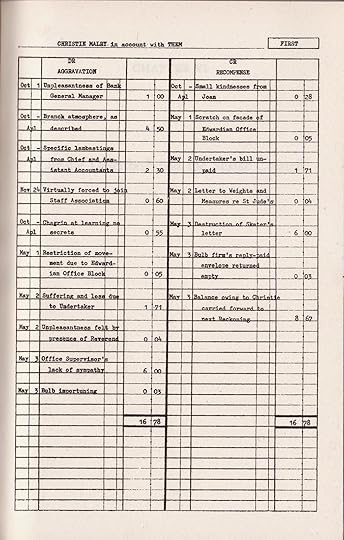

Christie had expected to have to work hard, and to find the work both uncongenial and menial, at first. What he did not expect was the atmosphere in which he was expected to work, and which was created by his fellow-employees or colleagues as they were in the habit of calling one another. This atmosphere was acrid with frustration, boredom and jealousy, black with acrimony, pettiness and bureaucracy.

We fondly believe that there is going to be a reckoning, a day upon which all injustices are evened out, when what we have done will beyond doubt be seen to be right, when the light of our justification blazes forth upon the world. But we are wrong: learn, then, that there is not going to be any day of reckoning, except possibly by accident.

God gives this couple, known as Adam and Eve, something called free will, which means they can act as they like. If they act as God does not like, however, they will get thumped. It is not by any means clear what God does or does not like.

“Hoy la novela únicamente debería proponerse ser divertida, brutal y corta"Eso nos dice el autor a través de uno de sus personajes y, en efecto, este es un libro divertido en ocasiones y brutal en otras, incluso divertido y brutal a la vez; es un libro donde se aúnan la brevedad del relato y la sencillez de su lectura; un libro diferente en su forma; un libro donde los personajes son conscientes de vivir en una novela y que incluso charlan con el narrador, mientras que este no pierde ocasión de provocar al lector, de incitarle (las apariencias de los personajes se dejan totalmente abiertas a nuestras preferencias, incluso escenas tan apetecibles como los encuentros sexuales son expresamente confinados a la mucha o poca imaginación del quizás decepcionado indolente lector) y hasta de comunicarle sus disquisiciones acerca de la escritura de esta novela en particular como referente de la novela en general.