What do you think?

Rate this book

180 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 1964

You spend all day teaching simple English to the third-year classes, fourteen-year-olds who have very little interest in learning: they are waiting only to leave school. You try to arouse their interest by pointing out how basic a knowledge of at least English must be. One boy says he can read the racing, and that that’s enough for him.

Albert sat, within himself, quite alone. His shattered state after each school day seemed to last longer and longer: soon it would be permanent, he felt, in spite of the end of term being near.

“They sit, large and awkward at the aluminium-framed tables and chairs, men and women, physically, whom you are for today trying to help to teach to take places in a society you do not believe in, in which their values already prevail rather than yours. Most will be wives and husbands, some will be whores and pounces: it’s all the same; any who think will be unhappy, all who don’t think will die”.

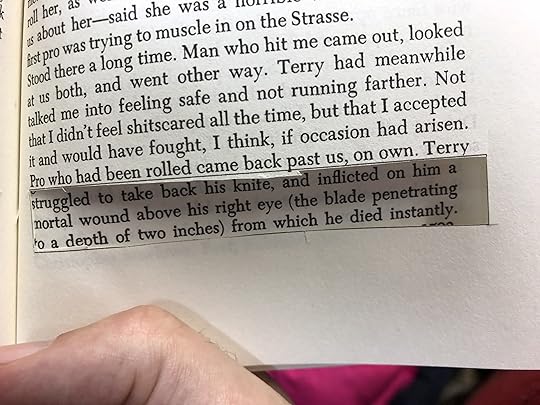

"The flakeworn paving was marked like a delta, like a chaotic candelabra, like a fistful of snakes. Albert paused, fascinated, then turned his head to look at the patterns in reverse. Never content to leave well alone, he unzipped his fly and attempted to impose the pattern of art on nature. Terry joined in laughing... : p.125