What do you think?

Rate this book

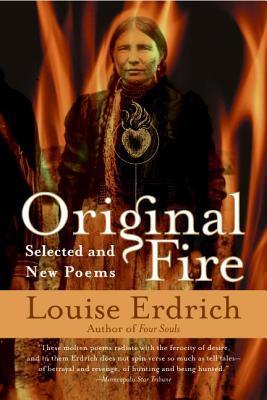

174 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 2003

Author Biography:

Louise Erdrich is one of the most gifted, prolific, and challenging of contemporary Native American novelists. Born in 1954 in Little Falls, Minnesota, she grew up mostly in Wahpeton, North Dakota, where her parents taught at Bureau of Indian Affairs schools. Her fiction reflects aspects of her mixed heritage: German through her father, and French and Ojibwa through her mother. She worked at various jobs, such as hoeing sugar beets, farm work, waitressing, short order cooking, lifeguarding, and construction work, before becoming a writer. She attended the Johns Hopkins creative writing program and received fellowships at the McDowell Colony and the Yaddo Colony. After she was named writer-in-residence at Dartmouth, she married professor Michael Dorris and raised several children, some of them adopted. She and Michael became a picture-book husband-and-wife writing team, though they wrote only one truly collaborative novel, The Crown of Columbus (1991).

The Antelope Wife was published in 1998, not long after her separation from Michael and his subsequent suicide. Some reviewers believed they saw in The Antelope Wife the anguish Erdrich must have felt as her marriage crumbled, but she has stated that she is unconscious of having mirrored any real-life events.

She is the author of four previous bestselling andaward-winning novels, including Love Medicine; The Beet Queen; Tracks; and The Bingo Palace. She also has written two collections of poetry, Jacklight, and Baptism of Desire. Her fiction has been honored by the National Book Critics Circle (1984) and The Los Angeles Times (1985), and has been translated into fourteen languages.

Several of her short stories have been selected for O. Henry awards and for inclusion in the annual Best American Short Story anthologies. The Blue Jay's Dance, a memoir of motherhood, was her first nonfiction work, and her children's book, Grandmother's Pigeon, has been published by Hyperion Press. She lives in Minnesota with her children, who help her run a small independent bookstore called The Birchbark.

Wind runs itself beneath the dust like a hand

lifting a scarf.

Mother, you say, and I hold you.

I tell you I was wrong, I am sorry.

So we listen to coyotes.

And their weeping is not of this earth

where it is called sorrow, but of another earth

where it is known as joy,

and I am able

to walk into the tree of forgiveness with you

and disappear there

and know myself.

At one time your touches were clothing enough.

Within these trees now I am different.

Now I wear the woods.

I lower a headdress of bent sticks and secure it.

I strap to myself a breastplate of clawed, roped bark.

I fit the broad leaves of sugar maples

to my hands, like mittens of blood.

Now when I say come,

and you enter the woods,

hunting some creature like the woman I was,

I surround you.

Light bleeds from the clearing. Roots rise.

Fluted molds burn blue in the falling light,

and you also know

the loneliness that you taught me with your body.

When you lie down in the grave of a slashed tree,

I cover you, as I always did.

Only this time you do not leave.

All day, asleep in clean grasses,

I dream of the one who could really wound me.

Not with weapons, not with a kiss, not with a look.

Not even with his goodness.

If I man was never to lie to me. Never lie me.

I swear I would never leave him.

But something queer happens when the heart is delivered.

When a child is born, sometimes the left hand is stronger.

You can train it to fail, still the knowledge is there.

[...]

Butch once remarked there was no one so deft

as my Otto. So true, there is great tact involved

in parting the flesh from the bones that it loves.

How we cling to the bones.

I've thought of her, so ordinary, rising every night,

scarred like the moon in her observance,

shaved and bound and bandaged

in rough blankets like a poor mare's carcass,

muttering for courage at the very hour

cups crack in the cupboards downstairs, and Otto

turns to me with urgency and power.

Tremendous love, the cry stuffed back, the statue

smothered in its virtue till the glass corrodes,

and the buried structure shows,

the hoops, the wires, the blackened arcs,

freeze to acid in the strange heart.

What kind of thoughts, Mary Kröger, are these?

With a headful of spirits,

how else can I think?

Under so many clouds,

such hooded and broken

old things. They go on

simply folding, unfolding, like sheets

hung to dry and forgotten.

And no matter how careful I watch them,

they take a new shape,

escaping my concentrations,

they slip and disperse

and extinguish themselves.

They melt before I half unfathom their forms.

Just as fast, a few bones

disconnecting beneath us.

It is too late, I fear, to call these things back.

Not in this language.

Not in this life.

I know it. The tongue is unhinged by the sauce.

But these clouds, creeping toward us

each night while the milk

gets scorched in the pan,

great soaked loaves of bread

are squandering themselves in the west.

Look at them: Proud, unpausing.

Open and growing, we cannot destroy them

or stop them from moving

down each avenue,

the dogs turn on their chains,

children feel through the windows.

What else should we feel our way through —

We lay our streets over

the deepest cries of the earth

and wonder why everything comes down to this:

The days pile and pile.

The bones are too few

and too foreign to know.

Mary, you do not belong here at all.

Sometimes I take back in tears this whole town.

Let everything be how it could have been, once:

a land that was empty and perfect as clouds.

But this is the way people are.

All that appears to us empty,

We fill.

What is endless and simple,

We carve, and initial,

and narrow

roads plow through the last of the hills

where our gravestones rear small

black vigilant domes.

Our friends, our family, the dead of our wars

deep in this strange earth

we want to call ours.