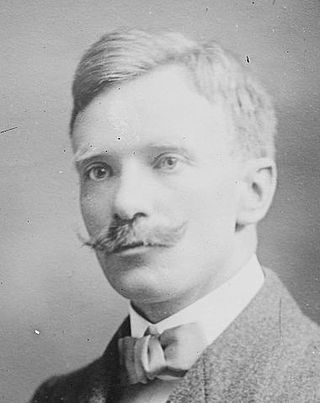

John Toland, author of 'Christianity not Mysterious' grave marker reads,

'"John Toland was born in Ireland new Londonderry, and in his youth studied in Scotland, in Ireland, and at Oxford [so on and so forth, more places he'd been to...] He cultivated the various literatures, and was acquainted with more than ten languages. The Champion of Truth, the Defender of Liberty, he bound himself to no man, on no man did he fawn. Neither threats nor misfortunes deterred him from his appointed course, which he pursued to the very end, always subordinating his own interests to the pursuit of the Good. His soul is united with the Heavenly Father from whom he first proceeded. Beyond any doubt he will live again unto eternity, yet there will never be another Toland. He was born on the 30th of November : for the rest consult his writings."

Such were the Rationalists.'"

What a difficult book to write about! Paul Hazard, who has a stunning breadth of knowledge on the murky period between the European Renaissance and The Enlightenment, that is, 1680-1715. I'll do my best to summarize, but please keep in mind, nothing will convey the full-force of this admirable work.

In this project, 'Crisis of the European Mind' Hazard furnishes the reader with figures of a changing Europe, Bayle, Simon, Spinoza, Locke, &c. intellects who were to pave the way for the likes of those we more readily hold to be the vanguard of Europe's new social order, an order which would bow to no higher authority than one's reason! And in this spirit of enquiry, information... in quantity above all else... is power! While some in vain still tried to unite a fragmented Europe once again under the banner of Christianity, some fully (and rashly) embraced this new attitude towards life, where men could be gods...

Hazard's allergic reading of this pseudo-classicism from 1680-1715 is an interesting and welcome point of view for this reader, as Hazard himself is undoubtedly a classicist, a traditionalist, and the temptation to make this book nothing more than a lamentation of some sort of European Golden Age runs thick—I was expecting some such screed upon how 'Europe lost its way' at many points throughout the work. Happily, this is no such thing! Hazard has a thorough, even, and fair approach to his subject, careful to make his thoughts known yet letting the currents of the subject's history determine his argument. Therefore : in this period of massive upheaval before the enlightenment, we lost so much, yet gained so much—whether this is something to cheer in celebration or beat your breast in mourning is quite up to you.

In the period covered by Hazard, we have a waining Classical/Ecumenical European culture, which at this point exists less as a source of inspiration for its European cultural constituency, and more as a simple force of of habit. What would take place was nothing short of a revolt against accepted cultural and philosophical models... authority would no longer be found to be a source of true inspiration, that is, the authority of the church as well as the Grecco-Roman cannon. Bow down to no authority! What did this entail?

Why, nothing short of an *entirely* different approach to knowledge. Instead of truth as those rare moments of revealing something about the spiritual character of life itself, truth is verification by quantification. Sources must be diverse, and no context can possibly be taken for granted. Yet, the more one searched the less one found! What indeed, was the measure of this new truth? This strange new criticality-as-all-costs brought forth bizarre arguments, such as 'just how many years from creation to the messiah??? the numbers don't add up!!!', a question so topsy-turvy in relation to any sort of 'truth factor' the bible may carry, it's a wonder creationists choose to make so much of it today...

Hazard illustrates the above very neatly with a short passage on History and its new relation to truth. The old history was an Epic history, deliberately a history of origins, the genealogy of a culture. The new history? Why, according to the new conception of truth, it couldn't be anything other than... well...

'A collection of fairy tales, when it treats the origin of nations; and, thereafter, a conglomeration of errors.'

Has this audacious spurning of all societal authority brought us closer to truth? One could make the case that this depends on 'their truth', which is already self defeating, since in the critical spirit, one can only admit that they know nothing since there is no authoritative/societal framework where truth may settle. One could easily make the case that Reason used in such a way only leads us towards vague conjecture and baffling perplexity. Hazard writes,

'What is lacking is any idea of how to handle it [knowledge] methodically. Men search here and enquire there, but without ever getting any definite response. We hunger for knowledge, and depart unsatisfied. And so we arrive at this melancholy conclusion, that the only really wise man is the man who knows that he knows nothing.'

Who were these freethinking *diletanti*? According to Hazard, they were 'dinner-party philosophers', rebel aristocrats who felt expansive from their comfortable vantage point. After all, it is a weak mind which allows nothing of a sense of mystery, and a simple one to reject it altogether. Mystery, for these upstarts, was merely that which was yet to be solved, nothing more (see John Toland above)...

In concert with this radical approach to knowledge, a couple of other things were turned on their heads. One : innovation became a boon, and Two : those pesky 'senses' which had ages before been regarded as untrustworthy and unreliable, where now the paragon of verification. Locke himself seats all knowledge within consciousness, against the backdrop of which is that semi-divinity which illudes all attempts at definition, 'Nature'. Nature is God, the Good! It all began to sound so familiar. Hazard notes that this period saw the founding of the first lodges of Freemasonry, those chapels to truth, liberty, and health.

Enough of this. What about the arts?

Complacency. It was indeed a *dead* culture, one which could think of no greater cultural triumph than following Aristotle's 'Poetics' to the letter, mimicking works of tradition, including the recent classics, Moliere, Corneille, Racine. Replacing the sarcophagus of the Classics and the Church(es) was a culture of, above all else, the use of one's Reason, which in turn informed an ooey gooey artistic sentimentality in revolt. Hazard's profound hatred for Opera, which he sees the embodiment of the new art of Modern Europe (summed up by Scarlatti's artistic purpose as 'because it makes one feel better') is nothing short of rib-tickling...

'It's a queer mix-up of poetry and music, in which the composer and the poet keep getting in each other's way, and put themselves to no end of trouble to produce a very mediocre result.'

Yet, this new sentimentality—was the pseudo-classical 'moralizing' art form a viable alternative? Where 'method' trumps genius? Surely not! A culture which does nothing more than produce shadows of a shadowy understanding of the classics is nothing to speak of.

If we are to take 'The West' for what it truly is we must take in to account that a great deal of Western culture is it's belief that it may stand aside and laugh at the adding machine while the cultural currents toss and turn about those who know no better. That a great deal of what the West wrought was a criticality which spared nothing, least of all itself. Are the bonds one may feel amongst others doomed to be provincial if enduring, and weak when broad? There is no simple answer... Though we usually find a simple answer at all costs which today comes in the solipsistic mantra, 'if it feels good, do it'. All is for the present moment, posterity be damned... an idea which runs deep in culture and so-called 'counter-culture' alike.

... yet without his being explicit, something tells me that Hazard doesn't believe in a conception of truth as bottomless disputation. Facts merely 'verified'... isn't it what we *do* with these facts that leads to Truth? In any case, Truth must surely be the most unfashionable of notions... surely, it cannot be an 'angry state of vigilance without a moment to call your own.'; such is this world. I'll leave us with a passage from the book, speculating on Bossuet's faith in the midst of critical argument...

'So he returns to the Gospel, not to argue and dispute, but to dwell in pious meditation upon its fairest pages, to taste the joy of calm, unquestioning belief, of tenderness and love. "Read again, O my soul, and rejoice in this sweet command to love." Mounting upward from height to height towards the celestial abodes of joy and love, he reached at last those realms sublime where, Prayer and Poetry merging into one, his words give utterance solely to his spirit's Yearning for Truth and Beauty that will never die.'

This might be the most incomplete review I've written so far.... I'm just going to have to be at peace with this.

—AF