What do you think?

Rate this book

240 pages, Hardcover

First published January 1, 1972

As for the fourth passenger, it seemed that he seldom traveled in a carriage with reserved seats. Most of the time he just sat there, his palms on his knees, as if wanting to hide the darns on his trousers. The sleeves of his black sateen shirt ended somewhere between his elbows and his wrists, and the white buttons on the collar and the chest made it look like the shirt of a child. There is something absurd and touching about the combination of white, childish buttons and the gray temples and exhausted eyes of an old man.

And the many millions confined in the camps rejoiced.

Columns of prisoners were marching to work in deep darkness. The barking of guard dogs drowned out their voices. And suddenly, as if the northern lights had flashed the words through their ranks: “Stalin has died.” As they marched on under guard, tens of thousands of prisoners passed the news on in a whisper: “He’s croaked… he’s croaked…” Repeated by thousand upon thousand of people, this whisper was like a wind. Over the polar lands it was still black night. But the ice in the Arctic Ocean had broken; you could now hear the roar of an ocean of voices.

The evening with his cousin had filled him with bitterness, and Moscow had seemed crushing and deafening. The vast tall buildings, the heavy traffic, the traffic lights, the crowds walking along the sidewalks – everything had seemed strange and alien. The whole city had seemed like a single great mechanism, schooled to freeze on the red light and to start moving again on the green…

I used to think that freedom was freedom of speech, freedom of the press, freedom of conscience. But freedom needs to include all of the lives of all of the people. Freedom is the right to sow what you want. It’s the right to make boots or shoes, it’s the right to bake bread from the grain you’ve sown and to sell it or not sell it as you choose. It’s the same whether you’re a locksmith or a steelworker or an artist – freedom is the right to live and work as you wish and not as you’re ordered to. But there’s no freedom for anyone – whether you write books, whether you sow grain, or whether you make boots.

“The sea was not freedom; it was a likeness of freedom, a symbol of freedom…How splendid freedom must be if a mere likeness of it, a mere reminder of it, is enough to fill a man with happiness.”

‘The criminals had, after all, confessed during the trials[…]they had been questioned in public by a man with a university degree[…]there had been no doubt about their guilt, not a shadow of a doubt.’

♥♥♥

Душата на Василий Гросман е вложена без остатък в кратката и напълно неизвестна за мен повест „Всичко тече“. Повестта е писана само „за чекмеджето“, в последните години от живота на Гросман (1955 – 1963 г.), след като е получил поредица от откази да бъде публикувана в СССР с аргумента „Защо към атомните бомби на враговете да добавяме и Вашата книга?“.

“Всичко тече“ е нож, диагноза, присъда и епитафия.

Нож, който реже с прецизни, елегантни, компетентни движения. Разкрива слой след слой с безжалостна яснота.

Диагноза на общество, управлявано от разумната необходимост да се избият и изселят милиони, за да дойде един по-добър свят.

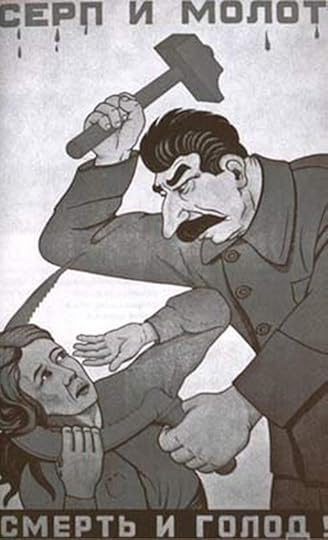

Присъда над всеки разум и идеология, опрадаващи такъв геноцид. Издадена присъда над Сталин - без право на обжалване, точно по любимия член 58.

Епитафия на самия Гросман. Свидетелство, че поне един човек е съумял да остане човек, че и с последния си дъх продължава да предава последния си репортаж, както когато е бил и кореспондент на фронта. Епитафия за лагерниците до полярния кръг - меншевики и болшевики, червеноармейци (там са и героите от “Как се каляваше стоманата” и “Небе на войната”, та дори и от “17 мига от пролетта”), белогвардейци, евреи, поляци и бесарабски българи, мъже и жени, майки и бащи, партийни апаратчици и селяни. Епитафия за жертвите на Гладомора - майки, деца, бащи, кротичкото малко семейство на Василий Тимофеевич - мъченици на ужасяващо неадекватни икономически решения и грабеж. Епитафия за оцелелите в тесните рамки на позволеното, с цената ма собствените им души.

И се редят въпроси, въпроси, въпроси...

1. Каква е тайната на руската душа?

„...руската душа е хилядолетна робиня. Какво ще даде на света една хилядолетна робиня, дори да е всесилна?“

Kакво е Русия? Има и може ли да има такова нещо като "свободна Русия". Цялото и минало се крепи на несвободата и нейните ползи. Цялото и настояще в периода 1955 – 1963 г. се крепи на тази несвобода.

“Бездната била в това, че развитието на Запада се оплождало от растежа на свободата, а развитието на Русия се оплождало от развитието на робството.”

„Нациите и държавите могат да се развиват в името на силата и напук на свободата! Това не беше храна за здрави, това бе наркотикът на неуспяващите, болните и слабите, изостаналите и битите.“

2. Защо революцията убива децата си и се изражда точно в тиранията, срещу която се е борила? Защо, веднъж победила, се крепи на институционализираното, безлично, бюрократизирано зло?

„На новата държава не и трябваха свети апостоли, екстатични строители, вярващи последователи. Новата държава нямаше нужда дори от слуги - само от служещи. И тревогата на държавата идваше от това, че нейните служещи се оказваха понякога прекалено дребно, при това лъжливо и крадливо племе.“

И все пак, революция е възможна, просто трябва да е правилната:

“Само онези, които посягат на основите на стара Русия - нейната робска душа - са революционери.”

Един от най-интересните портрети на Ленин е част от размислите и теразнията на Иван Григориевич/ Василий Гросман. Ленин – любителят на „Апасионата“. Ленин – който в спора търси само победата, но не и истината. Ленин – скромният. Ленин – безжалостният, който в името на бъдещата свобода избира да унищожи всички настоящи свободи.

3. Как човек да остане човек?

“Лагерните хора помагаха на Иван Григориевич да разбира хората от свободата. ... Еднакви бяха хората. Беше му жал за тях.”

„За човека да живее, значи да бъде свободен.“

Взе пак досега никоя система не е успяла да победи живота - и това е утешително.

Как би постъпил всеки от нас, ако беше там и тогава? Този отговор може би е по-добре да не знаем.