What do you think?

Rate this book

424 pages, Hardcover

First published April 28, 2011

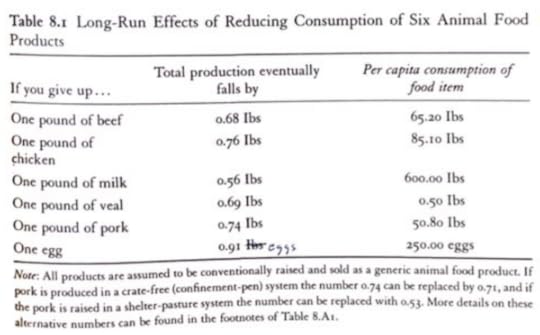

a permanent decision to reduce meant consumption (1) does ultimately reduce the number of animals on the farm and the amount of meat produced (2), but it has less than a 1-to-1 effect on the amount of meat produced.[1]

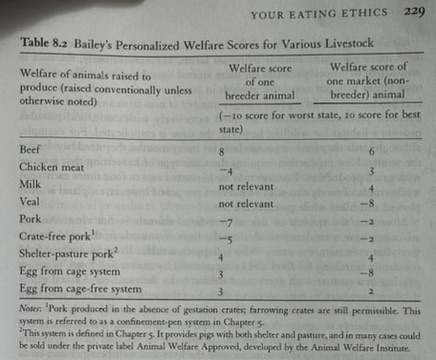

Although animal well-being can be enhanced in most typical animal production systems, we are quite certain that the overall level of animal welfare is higher in the broiler, dairy, and beef industries than the egg, pork, and veal industries. Beef cattle in particular experience high levels of well-being. A movement to improve the lives of egg-laying hens or sows would substantially reduce animal suffering, whereas an improvement in the beef industry would only make happy animals happier—both are praiseworthy, of course.[4]

In this chapter, we tended to focus primarily on the everyday life of farm animals. Animal advocacy groups will often mention a myriad other issues such as the transportation and slaughter of livestock. These issues, while important, are temporary experiences for the animal. We sought to describe the everyday life of farm animals, not the single worst days.[10]

Animals can be held captive in transport trucks for long periods of time. In the US, truck drivers are only required to stop animal transport trucks once every 28 hours, and this law is seldom enforced. In order to cut costs and maximize the amount of animals that can be transported at once, animals are often deprived of food and water for the entirety of their journey—up to 48 hours at a time—pushing them to the limits of how much starvation and dehydration they can endure. Can you imagine the stress of traveling for two days without stopping for food or water?

Given how many animals are stunned the wrong way, leaving them conscious through the worst moments of their lives, it’s safe to say that thousands upon thousands do feel pain, not only before the slaughter but during it. When their throats are slashed. When their bodies are boiled. When their limbs are severed.

Animals produced under organic systems probably experience higher levels of well-being than animals in non-organic systems, but the difference might not be as marked as many believe.[11]

Organic production prohibits the use of antibiotics (both therapeutic and subtherapeutic), which almost certainly lowers well-being as more animals become sick without access to antibiotic treatment. Animals that become sick on organic farms are either allowed to remain sick and potentially die or are segregated, given antibiotics, and are sold at a lower price in the non-organic market. Too many sick animals, we believe, do not receive proper treatment because the farmers fear the loss in income they will experience in having to sell the animal on the non-organic market.[12]

…organic producers have a difficult time meeting their animals’ dietary needs, and the animals suffer. A number of animal scientists in the US feel organic production is cruel for this reason.[13]

A final comment about the organic, AWA, and other such labels is warranted relating to consumer skepticism over the possibility of producers “cutting corners” by using practices that lower costs while still looking to sell at a premium under a brand. This skepticism is not entirely unfair. We have visited hog farms selling under a brand claiming to sell antibiotic-free pork, but the farmers told us plainly that antibiotics are used. We have visited hog farms claiming to produce under standards dictated by one of the humane labels but it was transparent the operation did not meet the standards… However, these are just a few exceptions to the many farms we have visited that are in compliance with the standards. Both the AWA and organic standards require routine farm inspections, which does help to minimize non-compliance.[14]