What do you think?

Rate this book

48 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 2010

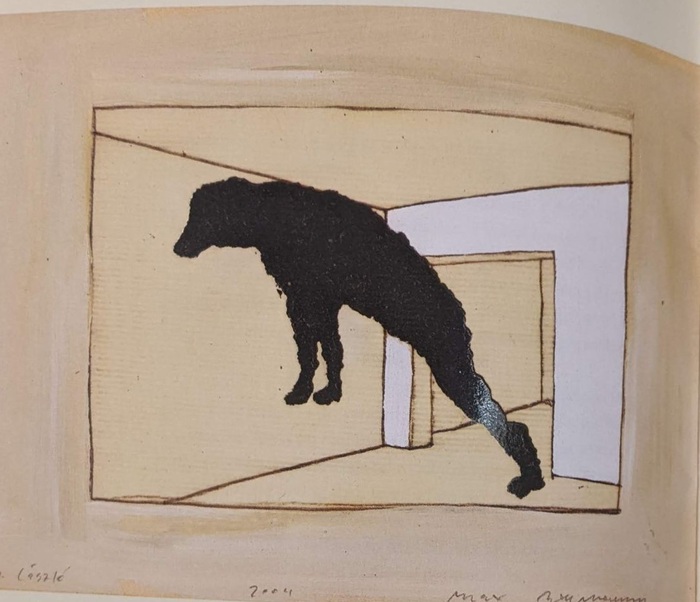

and that���s how life ends for you, because it is impossible to hide away from us, there is no depth within the earth that could be a refuge for you, we are here, above, here, look we���re watching from up here what you���re doing down there, but we don���t have to watch everything, because we know everything about you... I am inscrutable and indivisible and impenetrable...������And the end, as Krasznahorkai sees it here, is hardly something that can be prepared for or reckoned with because all of our cultural myths���and, too, the many ways in which we externalize power/knowledge systems, again to bring Foucault to mind���fail to consider that the true apocalypse does not come from outside, but from within:

every aspiration to the infinite is a trap... and don���t count on me emerging from below the earth, and it is not from the mountains or from the heavens that I shall arrive, every picture drawn in anxiety, ever word written down in horror, every voice sounded in anguish with which you try to prophesize me is senseless, for there is no need of prophecy, there is no need for you to evoke me before I arrive, it will be enough to see me then...A true revolt, then, is impossible, and Krasznahorkai���s pessimism is obviously on display here, but there is also an overriding sense of sympathy for this animal despite his malevolence and his destructive intent: ���if I jump up to sink my teeth into your throat, I hump into the trap definitively and inevitably, there is no point in speaking of escape. Into your throat.���