What do you think?

Rate this book

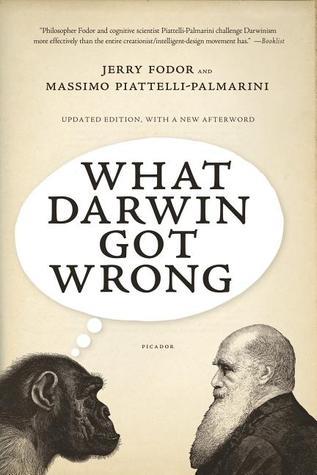

320 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 2010

Natural selection is supposed to explain why species have adaptive traits. But there is a plausible case in which natural selection does not select an adaptive trait because (in certain cases) natural selection cannot distinguish between a directly-correlated-with-fitness trait (causal relation) and a covariant-with-fitness trait (correlation).The work gives parallel examples for artificial selection (tameness/productivity was primarily selected but orthogonal curly tail, floppy ears, piebald colour traits also resulted), and reinforcement learning e.g. stereotypical behaviour of animals.