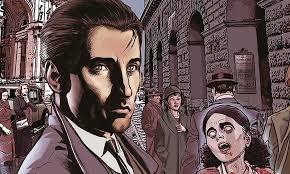

I Will Have Vengeance: The Winter of Commissario, by Maurizio de Giovanni, Commissario Ricciardi Series, bk1. An excellent introduction to an excellent series, a one of a kind policeman, set in Naples during the Italian reign of fascism.

“Luigi Alfredo Ricciardi, the man without a hat, was Commissario of Police with the Mobile Unit of the Regia Questura di Napoli. He was thirty-one years old, the same number of years that marked that century, nine of them under the fascist regime.”

The inescapable Incident. “he set about defining the limits of the Incident. He saw the dead. Not all of them, and not for long: only those who had died violently, and only for a period of time that revealed extreme emotion, the sudden energy of their final thoughts. He felt their emotion more than anything else. Each time he grasped their sorrow, their surprise, their rage, their misery. Even their love. This was what the Incident, his life sentence, was like. It came upon him like the ghost of a galloping horse, leaving him no time to avoid it; no warning preceded it, no physical sensation followed it except for the recollection of it. Yet another scar on his soul. … decided to study law, completed a thesis on criminal law, then joined the police; it was the only way to acknowledge those demands, to lighten that burden. In the world of the living, in order to bury the dead.”

Scene of the Crime and Pursuit. “those first long moments when the Commissario was getting to know the victim, focusing his legendary intuition, and tracking down the fundamentals needed to begin the pursuit. … from Piazza Dante to Piazza del Plebiscito he would cross an invisible boundary between two distinct realities: below, the wealthy city of aristocrats and the bourgeoisie, of culture and entitlement; above, the working-class neighbourhoods in which a different system of laws and regulations applied, equally rigid or perhaps more so. The sated city and the hungry one; the city of feasting and that of despair. … “There are no suicides, no homicides, no robberies or assaults, unless it is inevitable or essential. Not a word to the people, especially not to the press: a fascist city is clean and wholesome, there are no eyesores. The regime’s image is granitic, the citizen must have nothing to fear; we are the guardians of assurance.”

Death at the Opera. “Ricciardi heard singing in a soft voice: “Io sangue voglio, all’ira m’abbandono, in odio tutto l’amor mio finì . . . ”, I will have vengeance, My rage shall know no bounds, And all my love. Shall end in hate. … How much blood could there be in the human body? And how much soul, Ricciardi thought, listening to the clown’s song as he stood in the corner with his upraised hand. Which will disappear first, this stain on the carpet, or the echo of that aria in my head?”

Priest close at Hand. “looking at a multifaceted panorama. There was sorrow: an old sorrow, yet still alive. A sorrow that was an old friend. Loneliness. Intelligence, and a touch of irony, of sarcasm, when the theater director was sputtering beside him. It had only been a moment, but the priest had sensed a complex and troubled personality” … “He never blinked, and he wore a slight frown. Loneliness and sorrow, but also irony. You, me. Always with our uniforms on.” “The important thing is not to frighten people, with a uniform. People should feel reassured seeing it. And in order not to frighten people, you have to not be frightened.” The Commissario gave a faint start, as if the priest had suddenly slapped him. “And you, Father? Aren’t you ever frightened?” “Yes, almost always. But I ask for help. From the Almighty, from people. And I get over it.” “Bravo, Father. Bravo. Good for you. … “ help me, since I don’t know either one. Would you make a deal, with a policeman?” Sarcasm again. No smile, no wink. The unchanging green glass of his eyes. “A priest doesn’t make deals, Commissario. I will give you any information you need; but don’t ask me, now or later, to help you accuse someone. Yours is human justice. I deal with another justice: one that can also forgive.”

Home with Tata Rosa. “Rosa Vaglio was seventy years old. She was born the same year as Italy, but she took no notice of it, then or later. For her, the homeland had always been the Family, of which she was a staunch, resolute custodian. Rosa had often wondered where that sorrow in the eyes of the young Baroness came from. She had everything she wanted, leisure, affluence, a loving husband. But when she accompanied her on long walks through Fortino’s countryside, amid the pungent smell of goats and the peasants who stopped working to take off their hats, she felt that sorrow walking with them, one step behind. Ricciardi felt the warmth of the house seep gradually into his wind-chilled bones. The scent of wood fire in the stove, the aromas from the kitchen: garlic, beans, oil. The lamp next to his armchair was lit, the newspaper on the armrest. In the bedroom, his flannel robe, soft leather slippers and hairnet. My tata, he thought. Rosa watched him eat, like a wolf, as usual. Bent over his plate, quick, silent mouthfuls. He denies himself even that, she thought, the pleasure of savouring. He never savoured anything, not food or anything else. In him, the sorrow that in his mother had been concealed became evident. The same green eyes. The same sorrow. She sensed the turmoil of his thoughts, though she didn’t know what these thoughts were. She had been his family and he had become her reason for living. She would have given her eye teeth to see him laugh, at least once. She would have liked to see him at peace.”

A Neighbor. “There wasn’t a single night when he didn’t spend some time at the window, experiencing Enrica’s life vicariously. It was the only time he granted his tormented spirit a brief respite. He had never spoken to her, but there was no one, surely, who knew her better than he did. Once there she was in front of him, face to face. He still shuddered at the memory of the extraordinary mixture of pleasure, awkwardness, joy and terror he had felt. Afterwards, in the drowsy state that preceded sleep, or at the moments when he woke up, he would see those deep, dark eyes hundreds of times. That day he had fled, his heart leaping in his chest, a loud pounding in his ears.” Ricciardi thought again about the clown and his desperate last song. “Io sangue voglio, all’ira m’abbandono, in odio tutto l’amor mio finì . . . ” I will have vengeance . . . , and all my love shall end in hate. … as the wind rattled the shutters, Ricciardi drifted into a muddled dream in which a left-handed girl embroidered in front of a weeping clown.” … the next day. “And how that gaze was everything, a promise, a dream, even an ardent embrace. Thinking about it, she instinctively turned to the window. The curtain opposite was open. Lowering her eyes and blushing, Enrica hid a small smile: good evening, my love.” … “Ricciardi watched Enrica. He enjoyed her slow, methodical, precise movements.

It was the brightest moment of Ricciardi’s day: seeing her sitting there as she began embroidering with her left hand, her head slightly tilted to one side. It made his heart tremble.” Remembering. “Don Pierino telling him: “Seeing him up close, yesterday, made my heart tremble.”

The Morgue. “The man wheeled away the stretcher and no one ever saw Arnaldo Vezzi again in the flesh. “How absurd. Such greatness, so many dreams. The magic of an incomparable voice. The hubris, the omnipotence. Then, all this silence.” “Well then? In your opinion, how many chances does a person have in his life, to construct a little happiness?” “As many as he wants, Signora. Maybe none. But illusions, those for sure. Every day even, every moment. Illusions though. Only illusions.”

Return to the Opera. “I think the character Canio is one of the saddest of any opera. A man condemned to make people laugh, who instead is obsessed with not appearing ridiculous. It is hearing himself reminded by Beppe, Arlecchino, to perform, while he’s suffering from jealousy, that finally makes him lose control. … “you see it, do you understand, Father? I see it. I feel it, the sorrow of the dead who remain attached to a life they no longer have. I know it; I hear the sound of the blood draining away. The mind that deserts them, the brain clinging by the fingernails to the last shred as life runs out.” … “If you only knew how much death there is in your love, Father. How much hate. Man is imperfect, Father”

The victim… the investigation… killer(s) revealed. … Ricciardi Returns Home. “Even before raising her eyes from the embroidered pattern, she knew that the curtains in the window across the way had opened. As she went on embroidering, Enrica smiled.”