(A word of caution: the English translation by Alexis Lykland seems prone to mistakes, and should most likely be avoided. Artaud's style is difficult as it is, and it most certainly does not help to have odd cock-ups obfuscate the nebulous fabulations of our mad frog. For those who are interested, I'll list some mistakes at the end of this review.*)

I read Hans Johansson's Swedish translation, and I must say I was not expecting such a difficult read. The terminology is not abstruse, but the writing style makes use of very expressive language—which shows that I still have a lot to learn with Swedish. But what made this extra difficult wasn't simply my lacking Swedish skills; it was Artaud's own style, coupled with my own expectations.

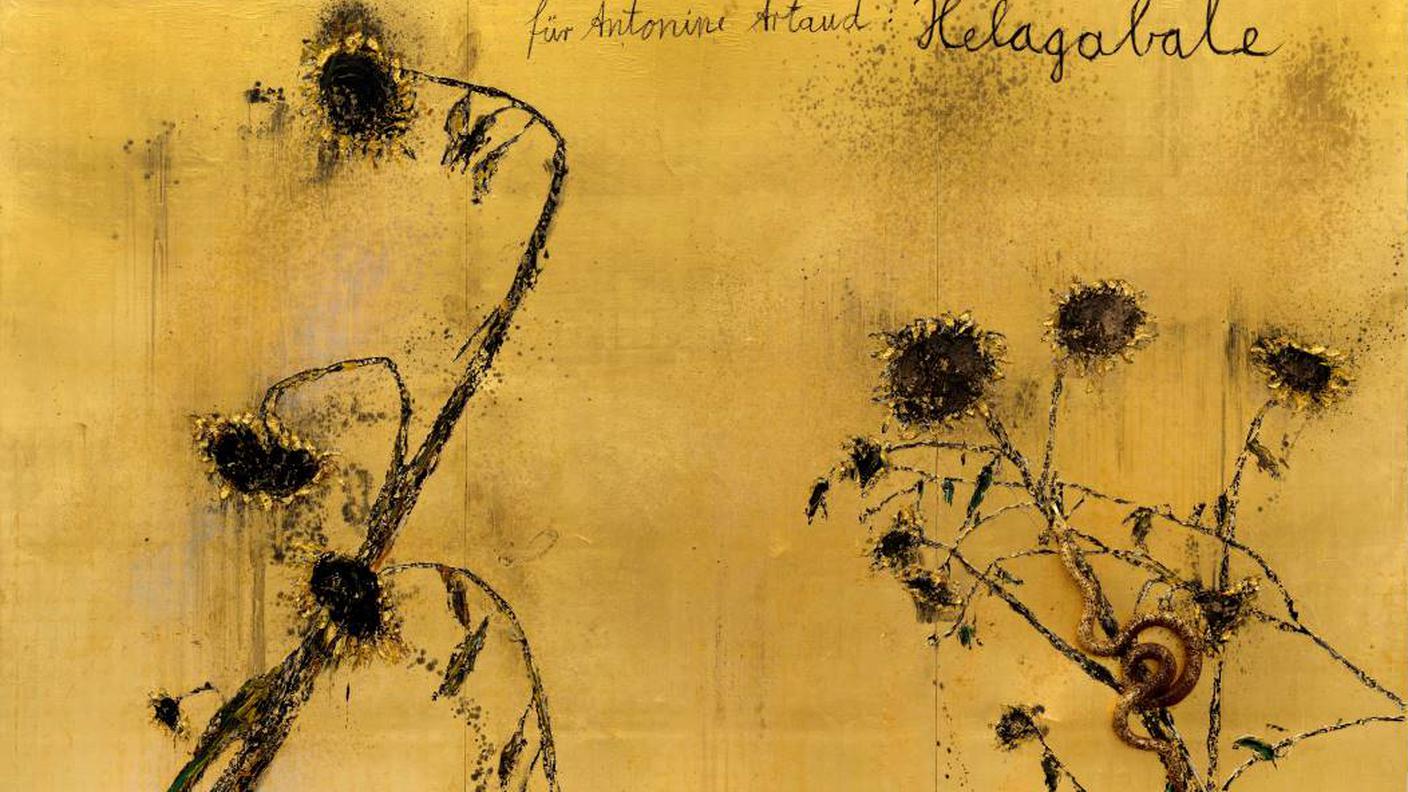

What I expected was a graphic and piquantly mad depiction of the degenerate life of Elagabalus. However, this is not a biography. It consists largely of Artaud's original commixing of mythological interpretations with historical data and long passages of mystical self-identification with the character of Elagabalus. It's only in the third and final part of the book that Artaud finally focuses on the crowned anarchist; before that, he waxes eloquent on the solar cult in Emesa, its rituals and their significances for himself, and the nature of the various principles that are mentioned in the work, such as the masculine and the feminine. Since I had to take in a lot of new vocabulary, it was obviously too Herculean of a task for me to decipher Artaud's inconsistent narration about Aries, the significance of colours and races of man in conjunction with various principles (whose essence Artaud seems to dispute and confirm contemporaneously), strange metaphysics and lopped-off cocks.

Yet this does not mean I didn't get anything out of the book. What struck me strongly was that Artaud seemed to lament how Apollonian the view of the historians are when it comes to the religious rites of eld (that's Swedish for "fire" as well—thought it had a nice double meaning to it). What we mostly have is a catalogue of names and their domains, yet what Artaud seems to be yearning for is the Dionysian reality behind those superficialities; the blood-chilling shrieks of complex rituals that confuse and elate the mind of those present.

He rued the fact that we have set the earth apart from the heavens, while for the "pagans", they were one—this theme of oneness and division runs throughout the text, and one could say, that Artaud is all for destroying the traditional onenesses that are upheld in the society, and replacing them, through division, with a new oneness. This is accomplished through anarchy and poetry, which create chaos in the midst of order, and let us see hidden structures of reality, which we can then unify through grand designs.

While the way Artaud depicts Elagabalus is far from a reliable account (not sure if there can ever be one), there definitely is a feeling of deep truth in it, a deep general truth. When one hears a long list of the emperor's atrocities, one is either aghast or sniggering with gusto—yet whichever reaction takes place, what nonetheless is very easy for anyone to assume is that Elagabalus was simply mad with power and lost the handle altogether in his excesses. Artaud's approach to the life of the emperor is to try to understand him through his native and religious background and through a complex religious metaphysics, wherein commingled lie fire, ithyphallics and menstrual blood, on top of which the masculine and the feminine wage their eternal war. He is also trying to understand him through his spirit: in Elagabalus, he sees a true mischievous spirit of anarchy, but also a deeply sensitive poet, who, due to his precociousness, knew how to both follow his vision of religion and to exploit his mighty position to this end. While any one of us could easily see Elagabalus as simply a foolish adolescent, whose anal glands mastered the voice of his faint reason, Artaud saw in him a battlefield of his native, Emesan principles, and a grand poet, who wanted to wage the war of anarchy in order to unify or uphold the principles he stood for. In breve, Artaud stopped short of a scandalous and sensational interpretation of Elagabalus and made him flesh.

Though inconsistent, digressive and sometimes simply incomprehensible, Artaud does manage to intimate a lot of things that seem to make sense in a vague way. His greatest feat, however, is in reminding us of the possible realities behind the dead letters of history, and of the soul-soaring qualities that religions and rites can have for those, who have the wherewithal and the mindset for them.

*****************

Unfortunately, I could not find the original French version online. Obviously, one cannot confidently state that something's a mistake by a simply comparison to another translation. That's why I used a random Spanish translation I found online as a third source. I don't know any Spanish, but it's pretty easy to determine whether a certain word is wrong or a certain section is missing through other means.

Here are some of the mistakes I've found:

P. 50:

EN: "I must say forthwith that the same name would never apply to two forms, made, apparently, so that one might devour the other."

However, in the other versions we also have something that could be translated to "but the same names were often a summary of two forms, which were apparently created to devour each other."

P. 53:

EN: "In love, formerly, there was knowledge."

SE: "However, in love there is knowledge."

P. 57:

EN: "And be it not said that Number, in the sense in which Pythagoras meant it, doesn't take us back to quantity but on the contrary, to the absence of quantity. For in its highest sense the written numeral is a symbol for what one can't manage to add up or measure."

SE: The second sentence begins with: "Or be it not said either that, in the highest sense, the written numeral..."

PP. 89–90

EN: "Let men gone astray here and there -priests, unimportant Galli -subject themselves to a gesture which finishes them off; certainly in that gesture there's something which intensifies the ritual's value, but Elagabalus, the Sun on earth, cannot lose the solar symbol, he mustn't function only in the abstract."

This one doesn't need a comparison. It's simply nonsensical: first there is a description of something concrete, which is then juxtaposed with an obvious abstract example. Yet the translator adds a gratuitous negation, which destroys the entire meaning of the section.