On June 8, 1924, George Mallory - handsome, charming, accomplished, a man so graceful he made climbing look like poetry - set out for the summit of Mount Everest with his junior climbing partner, Andrew "Sandy" Irvine. Their expedition had not gone to plan. But this, they believed, would be the final push - the successful summit. For the first time in recorded history, man would stand atop the highest point on Earth.

At 12:50 that afternoon, a fellow member of the expedition, Noel Odell, looked up from where he waited some fifteen hundred feet below. The clouds parted for an instant, and in that moment he saw two minuscule figures, moving swiftly far above him towards the summit: Mallory and Irvine, pushing on towards the top.

Then the clouds returned, and the figures vanished. They would never return.

.

.

.

Did Mallory and Irvine reach the summit of Everest, twenty-nine years before Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay? The feat would be all the more impressive for the sheer primitiveness of their gear. They wore layers of tweed and silk; they couldn't even wear crampons - the ubiquitous metal climbing spikes used for snow and ice - because the straps, when cinched over soft leather boots (no hardshell footwear for them!), would cut off circulation and inevitably cause frostbite.

Most hauntingly, perhaps - what exactly happened to Mallory and Irvine in the hours after the clouds closed back in? Did they turn back before the summit and stumble on their way down? Their distant watcher had noted with alarm that they were far behind their schedule (why were they so late?). Did they get caught in a snow squall, and have to find their route once again through the fresh snow? Did they reach the summit and then, short of daylight, have to bivouac out in the open, facing the killing winds in only their primitive gear? Did one man fall and, roped to the other, pull him down, too? Did a rope break mid-belay (again - primitive gear, with only a fraction of today's rope strength) and send one man crashing down, leaving the other to make his way down alone? Why did they leave their flashlight and compass behind? Had they brought a flashlight, would it have made a difference?

Could any of the tiny little plot points, these little choices that mapped out the slope towards disaster, have been changed, and in so doing could the outcome have been shifted, too? Where did it go wrong, and did it have to go wrong? This is, as always, the great mystery, the great haunting question that always tugs at us. In a world of human certainty and awareness, what little thing gave us away, and was it inevitable?

.

.

.

This book, co-written by Conrad Anker, one of the preeminent mountaineers of our time, and David Roberts, author and climber himself, begins with the moment in 1999 when Conrad Anker split off from his expedition, following a hunch and a sense of how mountains worked. The expedition had been formed with the express purpose of locating some remnant of the 1924 expedition; a researcher had tenaciously studied every scanty piece of evidence, every spare phrase and misted sighting from across the years, to create detailed instructions and analyses of where the bodies of the missing men should be found. For the reader, naturally rooting for Anker, there's no better moment than when his gamble pays off. Defying all studied logic, he spies something that doesn't fit. He finds a body: an old body.

.

.

.

The book jumps, chapter by chapter, from Anker's story of the 1999 expedition to Roberts's historical background and narrative of the 1924 expedition. It's fast-paced and engrossing; Roberts writes smoothly and eloquently, but so does Anker, albeit a little more simply.

Both sections intrigued me. Anker is a good storyteller, and his narrative reminds us that even with modern technology, Everest is not an easy climb. He traces not only the discovery of the body, but also his expedition's following push towards the summit and the very real, life-threatening obstacles they faced, including the unexpected need to rescue other stranded climbers. There's suspense in this narration: even with their crampons, their down suits, their modern ropes and their streamlined oxygen systems, will they make it? Who will make it? And, more importantly, will they make it back down? Nothing, on Everest, can be taken for granted, even now.

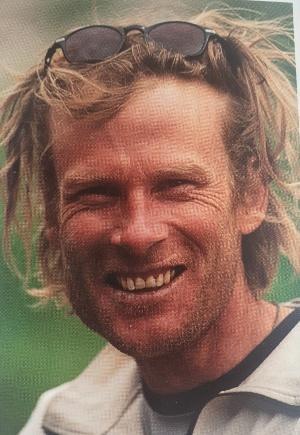

In his turn, Roberts dives into Mallory's background and character, touching on his family, his wife Ruth (whose photograph, curiously, was not found among Mallory's possessions), his Great War experience, and a telling injury. Roberts does a great job of capturing Mallory's personality - his charisma and his charm, his dedication and his absentmindedness. I would hardly know good climbing from bad climbing, but Roberts has so expertly culled his sources and translated them into prose that I felt Mallory's spell, his charisma, and his charm coming down from across the years, elevated far beyond the grainy distance of black-and-white photography. Roberts shares this observation from a contemporary of Mallory's:

"He would set his foot high against any angle of smooth surface, fold his shoulder to his knee, and flow upward and upright again on an impetuous curve... [T]he look, and indeed the result, were always the same - a continuous undulating movement so rapid and powerful that one felt the rock either must yield, or disintegrate... [he] could make no movement that was not in itself beautiful."

Some people have criticized the book's heaping praises of Anker. I think it's a just criticism; the adulation gets to be a little much. I like Anker, though, and didn't mind too much. If anyone in the climbing world deserves the praise, it's Anker. Instead, I read this praise as an attempt to rebut the nasty publicity the expedition received for the photographs and evidence it collected from the body.

The nasty publicity feels in some ways justified. One senses the discomfort the authors feel in reckoning with the grisly underside of what they'd sought. They'd been looking, after all, for bodies - human remains of men who have become legend, but who also remain deceased beloved to grieving families, including a living daughter. On Everest, death takes on a different tone; one need look no further than the ubiquitous Green Boots. In finding a body, where is the line between scientific research and human dignity? Where does our quest for answers turn a man into a piece of evidence?

In some ways the book falls short on these questions and others, which is too bad, because its narrative opens up the perfect opportunities for some serious questioning - not just of this individual case, but about Everest in general. Mallory, after all, snapped at a reporter "Because it's there," when he was asked why he wanted to climb Everest. He never meant that answer seriously, Roberts points out, and I think that stands true for all of what Everest, and these entwined stories, represents. To take "because it's there" at face value is to miss the depth beneath.

This was an engrossing and satisfying read. It's a great adventure tale with a good blend of history and action, well-paced, with some satisfying well-reasoned conclusions. With Anker as our detective, we learn a lot. He has a good eye for detail - the same eye and instinct that guided him to the body in the first place - and picks up on those little things that begin to paint a picture. Why did Mallory leave the flashlight behind? What does the gear, the evidence of the body reveal?

The writing and the explanations are also simple enough for the layperson (IE, me) to understand. It's hampered a little in its refusal to push the boundaries, to ask a few more questions, although Anker comes close, with some quiet reflections at the end. Still, this is a great introduction to two interesting mountaineers, and an engrossing primer on Everest itself. In the end, the mountain is always there.