Rich people destroy the world then get to sail away in a giant floating habitat to live in a utopian ideal until the end of time? That sounds . . . entirely plausible, if a bit inaccessible to the rest of us unless you think the world is going to be saved through stock buybacks.

Its not quite an oligarch's wet dream, though. Subtitled "A Mobile Utopia", it tries to tell the story of humanity through the eons as we outgrow our world and our solar system and perhaps eventually our conception of ourselves in an attempt to defy Time. Published at the end of the seventies, its one of several books in the annals of SF that try to come to terms with the potential survival of humanity over the course of millions of years and what we might evolve into in the process, taking it cues from two of the more notable authors in the subgenre, Arthur C Clarke and Olaf Stapledon. Clarke, who is blurbed on the cover as loving this book, gave us a blueprint in this with "Childhood's End" back in the Fifties, where an alien race rules over Earth while actually supervising their steps into the next stage of humanity's development. But even that work was decently influenced by Stapledon, who may not be as well-known today (he died in 1950), but who had a sense of scale was kind of dizzying. This book attempts to be a sort of love child between Stapledon's "Last and First Men" (a story about humanity evolving through the millennia) and "Star Maker" (a really really really longview of the Universe . . . to give you a sense of how large a temporal canvas he was operating under, the entire "Last and First Men" which covers a huge amount of time is about three paragraphs in "Star Maker"), while also trying to give us an idea of what society might be like all those years in the future.

To do that, he divides the book into three parts, all of which involve various members of the Bulero family (well, the last two parts involve the same one). The first part takes in 2021, in a world strangely not ravaged by a pandemic, political unrest and a climate crisis all at the same time and thus already feels like a utopia. The Bulero family has been eating out for free for decades on the discovery of an element they charmingly call "Bulerite", which is used to build massive cities and other structures. There's a fair amount of bad blood between patriarch Jack, estranged wife Janet, his brother Sam and son Richard but we don't get to experience too much of it before it becomes clear that maybe Richard should have invested a little more into R&D than stock buybacks because it turns out that Bulerite is inherently unstable and since every building was apparently all built at the same time, literally everything starts to fall apart simultaneously. Oops, to say the least and an object lesson as to why naming things after yourself isn't always the best idea, even if its good for the ego.

From there we get a sort of political thriller as everyone has to deal with the fallout of essentially destroying the world as the Bulero family escapes to the solar system's other colonies, who have to make decisions in the power vacuum that erupts, with Richard more interested in hanging out in the Asterome, a hollowed out asteroid that sees all the chaos and thinks that maybe this is a good time to exit stage right.

Of the three parts this is probably the most interesting from an action standpoint since at least stuff happens and we can indulge in the messed up family dynamics of the Buleros . . . except its soon clear that Richard doesn't have much of a personality besides discussing the concept of "macrolife" endlessly with his uncle and girlfriend (the story makes a big deal about the family meeting her for the first time and her kind of mysterious past but then goes nowhere with it, strangely). The swirl of events makes up for it to some extent as once the buildings start falling apart we're in a state of constant crisis where family is on the run. But it often feels like a means to an end as well, just developments required to get us where we need to be, on that sweet road to macrolife.

The macrolife takes center stage in the second part. Set centuries after the last part, it features John Bulero, a clone of Sam (but doesn't have his memories or personality so he might as well be a clone of me) and a relative youth in the macroworld that he's macrolivin' in. Humanity has filled out giant hollow asteroids and set forth into the galaxy, occasionally running into other bits of humanity that have set up civilizations on other worlds. They run into one of those more primitive branches of humanity first, where John has a not-great experience before stumbling back to Earth just in time to realize a) everyone didn't die and b) there's about to be a fairly momentous meeting and its not with them.

One of the problems with utopias is that writing about successful ones is really boring and writers for years have been trying to figure out ways around that, ranging from Ursula Le Guin's "The Dispossessed" to Austin Tappan Wright's "Islandia" to Alan Moore's post-nearly-everyone-getting-killed utopia at the end of "Miracleman" (before handing it off to Neil Gaiman to let him deal with the problem). Most of these writers either construct it a way that utopias work best for everyone who understands and buys into the ground rules, and what tension does occur is due to an inherent flaw that everyone is consciously (or otherwise) overlooking or the idea that maybe not everyone is benefitting equally, especially if you don't fit in. Zebrowski's contribution to the genre sort of acknowledges this but also subjects us to John Bulero being lectured endlessly about how great this utopia is, or reading his ancestor's many writings on macrolife. It makes for interesting reading if you're trying to dissect the concept of the utopia itself but its light on anything actually happening . . . other than a brief spurt of brutal combat there's very little action or tension . . . even negotiations with Earth and the subsequent visit from another party don't give us any conflict whatsoever, merely another example of how wonderful macrolife is.

Which may be true . . . hey, its Zebrowski's novel and its not like I'm going to be around to find out if he's right or we just ultimately immolate ourselves by setting all the greenhouse gases on fire. What it feels like he lacks here in spots is that sense of awe-inspiring scale that his predecessors were able to engender . . . I know the circumstances are everyday life for these people but if you can't make me go "whoa" at the prospect of giant hollowed out rocks cruising around the galaxies then maybe its worth rethinking the approach. We don't get much of a sense of how civilization could changed, especially with everyone so separated . . . one of the weirdest parts is when they go back to earth everyone converses normally like the macroworlders left last week . . . you would think some slippage would occur with language (we do get that, but with the primitive people and its more to demonstrate how civilization has gone backwards) and even frames of reference. I visit a country on the other side of the planet and there's some cultural gaps that have to be overcome since we don't come from the same background . . . I can't imagine two branches of humanity who haven't seen each other in centuries and have been living in two completely different environments aren't going to be on some level incomprehensible to each other. But its like me visiting my parents after having been away for a while, where they're more concerned I'm not going to sneak all my books back into the house.

Then we get to the third part in the far, far future where macrolife has gone viral and all the cool kids are doing it . . . except the cool kids are mostly one homogenous mass of experiences and emotions, like if someone had melted your yearbook into a single page. But there's no time to catch anyone on the flipside because the flipside is arriving shortly with the death of the known universe and to that end the overall macrolifers have resurrected an individualized version of John Bulero to somehow marshal them through the crisis and hopefully arrive on the other side, wherever that might be. Leaving aside that over billions of years of evolution the best they can think of is to bring back the clone of a rich dude from the 21st century to help convince everyone not to freak out because we've jumped so much from one part to the next without really getting a sense of the intervening period we're not really that invested in these people and it again becomes more about how you're invested in macrolife as a concept. So we essentially get a conversation between Bulero and the remainder of Macrolife about, you guessed it, macrolife while the universe comes to its natural end around them. Again, Zebrowski fails to really convey the sense of scale or just how weird a place the end of time would be (I feel like, even though its not scientific at all, Moorcock's "Dancers at the End of Time" series really nailed how entrophically weird things could get, just from a tonal standpoint) so its mostly just a guy we barely know arguing with italics until the book is over. Although the finale is uplifting, which barely feels like real life at all.

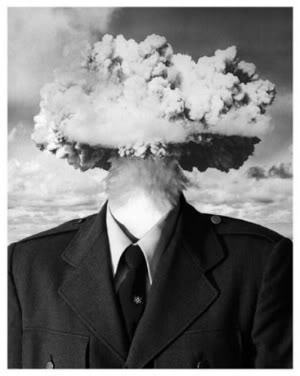

Its not a bad book, just a book that I'm not sure successfully builds upon what the books have gone before it managed to pull off. Zebrowski's got the "macrolife" concept to feed into the narrative but sometimes you wonder if his desire to illustrate macrolife from a storytelling standpoint gets in the way of telling an actual story. It just doesn't feel bold enough or widescreen enough in parts to really make you feel the scope of it, how much time is passing and how little of it we occupy in our brief lives. If he gets one feeling right, it’s the constant frustration of the characters to avoid death and in a sense the entire book is in a race against forever, people fighting against the limits of their own lives, then the life of their world, their species, their galaxy and eventually against the universe itself. That frustration, the most palpable element outside of the endless macrolife discussions, is probably the most optimistic bit about the book. These people want to live forever not simply because of a fear of death but a fear of the cessation that comes with it. To them its not a peace but a halt to learning, to exploring, to the very act of being, understanding the more there is to know the more we realize how much we don't know. That struggle to stick around so they can learn just one more thing is perhaps the most inspiring part of the book and I wish Zebrowski had highlighted it more. Because I may not be able to relate to humanity becoming one big italicized brain, but I can look at a future date on a calendar and be curious about what the world will look like and where we'll be. And I can do the math on my own age and realize that it may be just out of my feasible reach but I can understand the desire to be able to take another swipe with a feather at infinity and the hope that, somehow, I can be around for the another attempt.