The Old Curiosity Club discussion

Martin Chuzzlewit

>

MC Chapters 18-20

Chapter 19

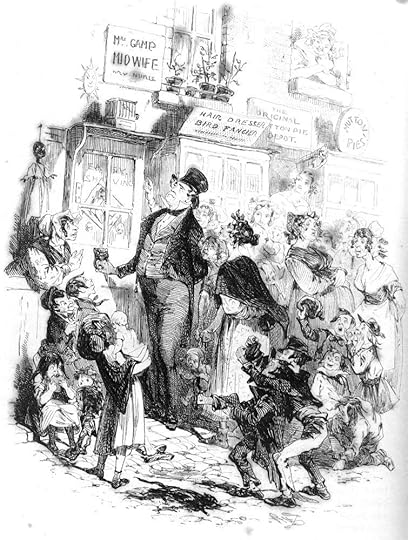

This is another chapter where I question why it had to be so long. There is nothing wrong with an author describing the funeral of a character. Still, the chapter seemed to be excessively long. That said, I will offer two reasons why it is so long. The first is the delightful introduction of Mrs Gamp, one of Dickens’s most masterfully created minor characters. She is one of Tristram’s favourite Dickensian characters. Perhaps he will comment further on her in this week’s discussions.

The chapter begins on an ominous note with Dickens telling us that “Mankind is evil in its thoughts and in its base constructions, and Jonas was resolved it should not have an inch to stretch into an ell against him.” Jonas decides to spare no expense on his father’s funeral and thus adopted the philosophy to “spend, and spare not!” For the contemporary readers of Dickens the description of the funeral preparations would have been a mixture of common knowledge and gentle amusement. For us, the arrangements are, perhaps, somewhat foreign. Let’s see what happens.

First, Pecksniff must find a proper functionary who would preside over the body of Anthony Chuzzlewit from a recommendation of the funeral director Mr Mould (what a perfect name for an undertaker). Pecksniff goes to find Mrs Gamp, which rhymes with damp, which fits quite nicely with Mr Mould. We are told that Mrs Gamp is “in the highest walk of art” and also functions as a midwife. This, she both introduces humans into the world and prepares other humans for their departure from the world. Pecksniff knocks on her window and tells Mrs Gamp she is wanted to attend a body. In describing Mrs Gamp Dickens recounts how she “had a face for all occasions.” With umbrella in hand, Mrs Gamp joins Pecksniff. Gamp is a fat old lady with a husky voice and a moist eye. She wears a rusty black gown. Perhaps her most obvious features are a red and swollen nose and she is always accompanied by a smell of spirits. We are told that she attended a “lying-in or a laying-out with equal zest and relish.” Often Gamp’s conversation is with a lady by the name of “Mrs Harris” whose name is always in quotation marks. Hmm...

Next, we learn that Mr Mould has been instructed to “put on my whole establishment of mutes,” provide drink for them and provide silver-plated handles, angel’s heads, and a profusion of feathers for the funeral procession. Mould’s instruction from Jonas is “to turn out something absolutely gorgeous.” I’m not sure what a gorgeous funeral should be like or look like, but no doubt the novel’s first readers would fully comprehend the comment. Jonas is insistent that Pecksniff bear witness to the quality of the mourning he is witnessing from Jonas. Chuffey, who is sincerely mourning Anthony Chuzzlewit, is escorted from the mourning room and Mrs Gamp takes his place and finds comfort with a bottle of liquor.

Thoughts

What are your impressions of Mrs Gamp and Mr Mould?

Before this chapter Jonas Chuzzlewit had been portrayed as rather cynical, controlling, and lacking respect for Anthony Chuzzlewit. In this chapter, he is very solicitous and insists on Pecksniff taking charge of the funeral arrangements. How can we account for this apparent change in character?

Chuffey appears to be the only person who truly mourns the passing of his friend and employer Anthony Chuzzlewit. What do you think Dickens’s point was in describing how he was treated by Jonas?

I would be remiss if I did not ask what your initial impressions of Mrs Smith are based on the reported conversation with Mrs Gamp. Who is she?

The solitary mourning goes on for a week. At times, Jonas feels uneasy and feels a presence in the house. Once, he believes he hears the sound of footsteps overhead and he cries out that the dead man was walking about his coffin. For his part, Pecksniff enjoyed a fine week of dining and Mrs Gamp continued to be very “punctual and particular in her drinking.” The day of the funeral arrives, the mutes were in place, the horses pranced, the horses snorted and in the words of Mr Mould “everything that money could do was done.” He assures Mrs Gamp that people like him and her “do good by stealth, and blush to have it mentioned in our little bills.” And so the funeral, or as Dickens refers to it, the show continues. Jonas glances “stealthily” out the coach window “to observe [the funeral procession’s effect] on the crowd.” It is Chuffey who mourns most sincerely; it is Chuffey who is criticized by the others for caring so much. Interestingly, Chuffey’s mourning causes Jonas to turn pale for a moment, but soon he recovers. On returning from the burial the home is found to be open and airy again. Mrs Gamp goes home, Mr Mould dines “gaily in the blossom of his family” the trappings of the funeral procession were put away and “the pageant of a few short hours ago” were written into the undertaker’s books. The churchyard gates were closed. The chapter ends with four words: “And that was all.”

Thoughts

Given what you have just read in this chapter what do you think Dickens’s opinion is about the type of funeral he describes in this chapter? What point(s) lead your to this conclusion?

There are a few subtle suggestions about the true nature of Jonas in this chapter. How has Dickens increased our understanding and insight into his character in this chapter?

This is another chapter where I question why it had to be so long. There is nothing wrong with an author describing the funeral of a character. Still, the chapter seemed to be excessively long. That said, I will offer two reasons why it is so long. The first is the delightful introduction of Mrs Gamp, one of Dickens’s most masterfully created minor characters. She is one of Tristram’s favourite Dickensian characters. Perhaps he will comment further on her in this week’s discussions.

The chapter begins on an ominous note with Dickens telling us that “Mankind is evil in its thoughts and in its base constructions, and Jonas was resolved it should not have an inch to stretch into an ell against him.” Jonas decides to spare no expense on his father’s funeral and thus adopted the philosophy to “spend, and spare not!” For the contemporary readers of Dickens the description of the funeral preparations would have been a mixture of common knowledge and gentle amusement. For us, the arrangements are, perhaps, somewhat foreign. Let’s see what happens.

First, Pecksniff must find a proper functionary who would preside over the body of Anthony Chuzzlewit from a recommendation of the funeral director Mr Mould (what a perfect name for an undertaker). Pecksniff goes to find Mrs Gamp, which rhymes with damp, which fits quite nicely with Mr Mould. We are told that Mrs Gamp is “in the highest walk of art” and also functions as a midwife. This, she both introduces humans into the world and prepares other humans for their departure from the world. Pecksniff knocks on her window and tells Mrs Gamp she is wanted to attend a body. In describing Mrs Gamp Dickens recounts how she “had a face for all occasions.” With umbrella in hand, Mrs Gamp joins Pecksniff. Gamp is a fat old lady with a husky voice and a moist eye. She wears a rusty black gown. Perhaps her most obvious features are a red and swollen nose and she is always accompanied by a smell of spirits. We are told that she attended a “lying-in or a laying-out with equal zest and relish.” Often Gamp’s conversation is with a lady by the name of “Mrs Harris” whose name is always in quotation marks. Hmm...

Next, we learn that Mr Mould has been instructed to “put on my whole establishment of mutes,” provide drink for them and provide silver-plated handles, angel’s heads, and a profusion of feathers for the funeral procession. Mould’s instruction from Jonas is “to turn out something absolutely gorgeous.” I’m not sure what a gorgeous funeral should be like or look like, but no doubt the novel’s first readers would fully comprehend the comment. Jonas is insistent that Pecksniff bear witness to the quality of the mourning he is witnessing from Jonas. Chuffey, who is sincerely mourning Anthony Chuzzlewit, is escorted from the mourning room and Mrs Gamp takes his place and finds comfort with a bottle of liquor.

Thoughts

What are your impressions of Mrs Gamp and Mr Mould?

Before this chapter Jonas Chuzzlewit had been portrayed as rather cynical, controlling, and lacking respect for Anthony Chuzzlewit. In this chapter, he is very solicitous and insists on Pecksniff taking charge of the funeral arrangements. How can we account for this apparent change in character?

Chuffey appears to be the only person who truly mourns the passing of his friend and employer Anthony Chuzzlewit. What do you think Dickens’s point was in describing how he was treated by Jonas?

I would be remiss if I did not ask what your initial impressions of Mrs Smith are based on the reported conversation with Mrs Gamp. Who is she?

The solitary mourning goes on for a week. At times, Jonas feels uneasy and feels a presence in the house. Once, he believes he hears the sound of footsteps overhead and he cries out that the dead man was walking about his coffin. For his part, Pecksniff enjoyed a fine week of dining and Mrs Gamp continued to be very “punctual and particular in her drinking.” The day of the funeral arrives, the mutes were in place, the horses pranced, the horses snorted and in the words of Mr Mould “everything that money could do was done.” He assures Mrs Gamp that people like him and her “do good by stealth, and blush to have it mentioned in our little bills.” And so the funeral, or as Dickens refers to it, the show continues. Jonas glances “stealthily” out the coach window “to observe [the funeral procession’s effect] on the crowd.” It is Chuffey who mourns most sincerely; it is Chuffey who is criticized by the others for caring so much. Interestingly, Chuffey’s mourning causes Jonas to turn pale for a moment, but soon he recovers. On returning from the burial the home is found to be open and airy again. Mrs Gamp goes home, Mr Mould dines “gaily in the blossom of his family” the trappings of the funeral procession were put away and “the pageant of a few short hours ago” were written into the undertaker’s books. The churchyard gates were closed. The chapter ends with four words: “And that was all.”

Thoughts

Given what you have just read in this chapter what do you think Dickens’s opinion is about the type of funeral he describes in this chapter? What point(s) lead your to this conclusion?

There are a few subtle suggestions about the true nature of Jonas in this chapter. How has Dickens increased our understanding and insight into his character in this chapter?

Chapter 20

Did you find the previous chapter curious? Jonas Chuzzlewit seemed rather contrite, Pecksniff rather calm, orderly, and competent, and Sarah Gamp, well, she was totally delightful. What’s next? The epigraph to this chapter is “It’s a Chapter of Love.” Love, well, Dickens may be misleading us with that phrase just a bit.

The chapter begins with discussion of a financial transaction. Not one of a business nature, but rather one of a matrimonial dowry which is, I guess, a form of business transaction. In the first sentence of the chapter Jonas “complacently” asks Pecksniff how much he means to give his daughters when they marry. When Pecksniff comments that such a question is “a very singular inquiry” we read that Jonas “retorted ... with no great favour, ‘but answer it, or let it alone, One or the other.’” Can you hear the air going out of the ballon? Jonas is, once again, a calculating person. The previous chapter appears to have been Jonas playing the part of the grieving son. We need to remember this. Jonas is an actor, a trickster, a deceiver. Pecksniff is taken aback by the abruptness of Jonas’s inquiry, especially so soon after the burial of his father. With “captivating bluntness” Jonas asks Pecksniff what the dowry would be if he was to be his son-in-law. With “dejected vivacity” Pecksniff believes Jonas is referring to Cherry who is Pecksniff’s “staff ... script ... treasure.” Further into their conversation we find out that Cherry is Pecksniff’s favourite daughter and her dowry would be £4000. Pecksniff sees this amount as a sacrifice. Dickens tells us that Pecksniff has been able to build his savings “with a hook in one hand and a crook in the other, scraping all sorts of valuable odds and ends into his pouch.” (my italics.)

Thoughts

Jonas has not waited long to turn into his other self. Greed, money, and perhaps a scam or two are part of his true character. Could it be that he would even marry someone in order to obtain money? Is marriage to a daughter of Pecksniff even possible?

From Pecksniff’s point of view, what benefit would it be to marry Cherry, his favourite daughter, off to Jonas Chuzzlewit?

Given what we have read so far in this chapter, how are we to better understand what occurred in the last chapter?

I added italics to the word “crook” in the quotation above. To what degree do you think Dickens meant this word to have multiple meanings? What are the suggested meanings that could be applied to this word?

As the coach ride continues Jonas becomes quiet and seems to run the figures of a profitable marriage to Cherry Pecksniff in his head. They stop off at an inn for some refreshment and Jonas tells Pecksniff that he will pay the bill since Pecksniff has been living well off Jonas for the past week. Pecksniff is taken by surprise, but quickly recovers, puts on his false face again and off they go. At the next stop the same event occurs. Jonas is the alpha male and Pecksniff attempts to keep up with Jonas and his attitude. When Pecksniff attempts to introduce Anthony Chuzzlewit into the conversation he is told “fiercely” by Jonas to “drop it.” Pecksniff appears to have met his match. Jonas is bold, calculating, and aggressive. Pecksniff’s passive-aggressive personality has been neutralized.

At Pecksniff’s home he and Jonas first see Cherry who is the perfection of the domesticated woman. She is sitting at a table “white as the driven snow, before the kitchen fire, making up accounts!” Indeed, she even described as having a “bunch of keys within a small basket at her side.” Cherry is the model of domesticity. Meanwhile, we learn that Merry is upstairs reading. As Dickens tells the reader “Domestic details do not charm her.” Merry has spirit, and this appears to attract the attention of Jonas. When Merry attempts to leave the room Jonas brings her back “after a short struggle in the passage which scandalized Miss Cherry very much. After much hugging, pinching, and other somewhat notorious activity no doubt to some initial Victorian readers of the novel Jonas reveals that he is attracted only to Merry, and any other intentions towards Cherry were, in fact, calculated to be directed to Merry. With that, Jonas proposes to Merry. She refuses. Jonas tells her that “any trick is fair in love.” He then says “we’re a pair, if ever there was one.”

Cherry tells her father what went on after he left the room. Pecksniff then goes to see Jonas and tells him “the dearest wish of my heart is now fulfilled.” To this, Jonas responds that the marriage of himself to Merry Pecksniff will cost Mr Pecksniff an additional £1000. “You get off very cheap that way, and haven’t a sacrifice to make.” Well, let’s pause here and figure out what has just happened, and what it all may mean. We learn that any attentions that Jonas paid to Cherry were all designed around his plan to woo Merry. We learn that Jonas drives a hard bargain and wants £4000 to marry one of Pecksniff’s daughter. When Pecksniff agrees, Jonas then pursues Merry, gets a begrudging commitment to marry him, and then ups the dowry to £5000. When he tells Pecksniff the amount is a bargain and that Pecksniff doesn’t have to make a “sacrifice” it appears he means that he will take the spirited and coltish daughter Merry and leave Pecksniff with the docile obedient daughter Cherry.

Thoughts

Do you think Jonas had planned the marital scheme in advance of this evening? Why/why not?

What reasons would Jonas have for favouring Merry over Cherry?

The epigraph for this chapter was “It’s a Chapter of Love.” To what extent do you see this chapter as one of:

the love of making money in any and all ways possible?

the enjoyment or love of tricking another individual?

a comment of what love should not be like?

the love of hypocrisy?

another form of love not suggested above?

Out of curiosity, do you think that because of Merry Pecksniff’s spirited character she may turn out to be like Dolly Varden?

Pecksniff’s world is yet to be disrupted in another way before the end of the chapter. Tom Pinch wants a word with Pecksniff. Tom tells Pecksniff that Martin Chuzzlewit and his attendant Mary are in town and are on their way to Pecksniff’s home right now. Pecksniff is shaken. The thought that he may lose the old man’s favour “almost as soon as they were reconciled, through the mere fact of having Jonas in the house” shakes him to the core. Can he hide Jonas in the coal cellar? Can he calm down the hysterics of his daughters. What to do? And then there is a knocking at his door.

Reflections

Jonas Chuzzlewit seems to be a very cold, cruel, and calculating individual. When he is compared to Martin Chuzzlewit, Martin seems to be almost likeable. With one of Pecksniff’s daughters spoken for, or should I say paid for, will Dickens marry off Cherry in the coming chapters, and, if so, to who?

It appears that Pecksniff has met his match in Jonas. What is Jonas ultimately capable of and when will we see more of his brisk and calculating personality? No doubt, Dickens has big plans for him in the coming chapters.

I hope you have enjoyed meeting Mrs Gamp. With luck we will meet her again in the novel. As for our friends Martin Chuzzlewit and Mark Tapley, where will their American adventure lead them next? Will Mary remain faithful to Martin and where did that £20 come from?

Did you find the previous chapter curious? Jonas Chuzzlewit seemed rather contrite, Pecksniff rather calm, orderly, and competent, and Sarah Gamp, well, she was totally delightful. What’s next? The epigraph to this chapter is “It’s a Chapter of Love.” Love, well, Dickens may be misleading us with that phrase just a bit.

The chapter begins with discussion of a financial transaction. Not one of a business nature, but rather one of a matrimonial dowry which is, I guess, a form of business transaction. In the first sentence of the chapter Jonas “complacently” asks Pecksniff how much he means to give his daughters when they marry. When Pecksniff comments that such a question is “a very singular inquiry” we read that Jonas “retorted ... with no great favour, ‘but answer it, or let it alone, One or the other.’” Can you hear the air going out of the ballon? Jonas is, once again, a calculating person. The previous chapter appears to have been Jonas playing the part of the grieving son. We need to remember this. Jonas is an actor, a trickster, a deceiver. Pecksniff is taken aback by the abruptness of Jonas’s inquiry, especially so soon after the burial of his father. With “captivating bluntness” Jonas asks Pecksniff what the dowry would be if he was to be his son-in-law. With “dejected vivacity” Pecksniff believes Jonas is referring to Cherry who is Pecksniff’s “staff ... script ... treasure.” Further into their conversation we find out that Cherry is Pecksniff’s favourite daughter and her dowry would be £4000. Pecksniff sees this amount as a sacrifice. Dickens tells us that Pecksniff has been able to build his savings “with a hook in one hand and a crook in the other, scraping all sorts of valuable odds and ends into his pouch.” (my italics.)

Thoughts

Jonas has not waited long to turn into his other self. Greed, money, and perhaps a scam or two are part of his true character. Could it be that he would even marry someone in order to obtain money? Is marriage to a daughter of Pecksniff even possible?

From Pecksniff’s point of view, what benefit would it be to marry Cherry, his favourite daughter, off to Jonas Chuzzlewit?

Given what we have read so far in this chapter, how are we to better understand what occurred in the last chapter?

I added italics to the word “crook” in the quotation above. To what degree do you think Dickens meant this word to have multiple meanings? What are the suggested meanings that could be applied to this word?

As the coach ride continues Jonas becomes quiet and seems to run the figures of a profitable marriage to Cherry Pecksniff in his head. They stop off at an inn for some refreshment and Jonas tells Pecksniff that he will pay the bill since Pecksniff has been living well off Jonas for the past week. Pecksniff is taken by surprise, but quickly recovers, puts on his false face again and off they go. At the next stop the same event occurs. Jonas is the alpha male and Pecksniff attempts to keep up with Jonas and his attitude. When Pecksniff attempts to introduce Anthony Chuzzlewit into the conversation he is told “fiercely” by Jonas to “drop it.” Pecksniff appears to have met his match. Jonas is bold, calculating, and aggressive. Pecksniff’s passive-aggressive personality has been neutralized.

At Pecksniff’s home he and Jonas first see Cherry who is the perfection of the domesticated woman. She is sitting at a table “white as the driven snow, before the kitchen fire, making up accounts!” Indeed, she even described as having a “bunch of keys within a small basket at her side.” Cherry is the model of domesticity. Meanwhile, we learn that Merry is upstairs reading. As Dickens tells the reader “Domestic details do not charm her.” Merry has spirit, and this appears to attract the attention of Jonas. When Merry attempts to leave the room Jonas brings her back “after a short struggle in the passage which scandalized Miss Cherry very much. After much hugging, pinching, and other somewhat notorious activity no doubt to some initial Victorian readers of the novel Jonas reveals that he is attracted only to Merry, and any other intentions towards Cherry were, in fact, calculated to be directed to Merry. With that, Jonas proposes to Merry. She refuses. Jonas tells her that “any trick is fair in love.” He then says “we’re a pair, if ever there was one.”

Cherry tells her father what went on after he left the room. Pecksniff then goes to see Jonas and tells him “the dearest wish of my heart is now fulfilled.” To this, Jonas responds that the marriage of himself to Merry Pecksniff will cost Mr Pecksniff an additional £1000. “You get off very cheap that way, and haven’t a sacrifice to make.” Well, let’s pause here and figure out what has just happened, and what it all may mean. We learn that any attentions that Jonas paid to Cherry were all designed around his plan to woo Merry. We learn that Jonas drives a hard bargain and wants £4000 to marry one of Pecksniff’s daughter. When Pecksniff agrees, Jonas then pursues Merry, gets a begrudging commitment to marry him, and then ups the dowry to £5000. When he tells Pecksniff the amount is a bargain and that Pecksniff doesn’t have to make a “sacrifice” it appears he means that he will take the spirited and coltish daughter Merry and leave Pecksniff with the docile obedient daughter Cherry.

Thoughts

Do you think Jonas had planned the marital scheme in advance of this evening? Why/why not?

What reasons would Jonas have for favouring Merry over Cherry?

The epigraph for this chapter was “It’s a Chapter of Love.” To what extent do you see this chapter as one of:

the love of making money in any and all ways possible?

the enjoyment or love of tricking another individual?

a comment of what love should not be like?

the love of hypocrisy?

another form of love not suggested above?

Out of curiosity, do you think that because of Merry Pecksniff’s spirited character she may turn out to be like Dolly Varden?

Pecksniff’s world is yet to be disrupted in another way before the end of the chapter. Tom Pinch wants a word with Pecksniff. Tom tells Pecksniff that Martin Chuzzlewit and his attendant Mary are in town and are on their way to Pecksniff’s home right now. Pecksniff is shaken. The thought that he may lose the old man’s favour “almost as soon as they were reconciled, through the mere fact of having Jonas in the house” shakes him to the core. Can he hide Jonas in the coal cellar? Can he calm down the hysterics of his daughters. What to do? And then there is a knocking at his door.

Reflections

Jonas Chuzzlewit seems to be a very cold, cruel, and calculating individual. When he is compared to Martin Chuzzlewit, Martin seems to be almost likeable. With one of Pecksniff’s daughters spoken for, or should I say paid for, will Dickens marry off Cherry in the coming chapters, and, if so, to who?

It appears that Pecksniff has met his match in Jonas. What is Jonas ultimately capable of and when will we see more of his brisk and calculating personality? No doubt, Dickens has big plans for him in the coming chapters.

I hope you have enjoyed meeting Mrs Gamp. With luck we will meet her again in the novel. As for our friends Martin Chuzzlewit and Mark Tapley, where will their American adventure lead them next? Will Mary remain faithful to Martin and where did that £20 come from?

As a reader, I find Gamp very funny! I did think a couple of times, about what would it be like if you really need a nurse, and all you can afford is a woman who is always on the verge of being drunk? She also doesn't come across as the caring type. In a way she is a sad kind of character too.

Jonas flaunts his hypocrisy in a way Pecksniff can only dream of. The only love he has, seems to be the love for money. It is clear he marries for money, and has thought or dreamed about killing his father for money a couple of times. Even his own conscience wouldn't have put it past him to do so, and to drown it he throws this lavish funeral - and for what the outside world might think, off course. However, in the end the only ones who really care are Mrs. Gamp and Mr. Mould and his men, because they are on the receiving end of Jonas' temporary burst of spending.

I read chapter 19 mostly as a mirror to a society where keeping up appearances is everything. If you pay for an expensive funeral, you're honorable, but real grief is not. It is okay to drink a lot, as long as it is not mentioned as such, and as long as you don't say you want a drink - put the bottle in the room, and 'oh, I was so busy I didn't realize I took so many sips', while the bottle is now empty, that kind of things.

In chapter 18 and 19 I also saw some connections to 'A Christmas Carol'. There's the poor clerk (here Chuffy) who gets scolded for behaving with emotions, in this case grief instead of merriment. There's two partners in a firm - here a father and a son, but wasn't Scrooge the one who inherited all from Marley too? One dies, and the other gets visited by the ghost. In Jonas' case mostly in his mind, but still. It makes me curious if there will be some kind of change in Jonas' behaviour too, although as for now I'm afraid there won't be.

As for chapter 20, there really is no love lost between Jonas and the two sisters, is there? Although Merry really seems to care about her sister's wounded feelings, she picks up being engaged to Jonas quickly enough, and she plays along with his teasing and his physically handling her easily enough too. Cherry, I think is more wounded in her pride because she misunderstood Jonas' intentions than she was wounded in her love for him. But that can also be my interpretation, because I cannot imagine someone falling in love with a miser like that.

Jonas flaunts his hypocrisy in a way Pecksniff can only dream of. The only love he has, seems to be the love for money. It is clear he marries for money, and has thought or dreamed about killing his father for money a couple of times. Even his own conscience wouldn't have put it past him to do so, and to drown it he throws this lavish funeral - and for what the outside world might think, off course. However, in the end the only ones who really care are Mrs. Gamp and Mr. Mould and his men, because they are on the receiving end of Jonas' temporary burst of spending.

I read chapter 19 mostly as a mirror to a society where keeping up appearances is everything. If you pay for an expensive funeral, you're honorable, but real grief is not. It is okay to drink a lot, as long as it is not mentioned as such, and as long as you don't say you want a drink - put the bottle in the room, and 'oh, I was so busy I didn't realize I took so many sips', while the bottle is now empty, that kind of things.

In chapter 18 and 19 I also saw some connections to 'A Christmas Carol'. There's the poor clerk (here Chuffy) who gets scolded for behaving with emotions, in this case grief instead of merriment. There's two partners in a firm - here a father and a son, but wasn't Scrooge the one who inherited all from Marley too? One dies, and the other gets visited by the ghost. In Jonas' case mostly in his mind, but still. It makes me curious if there will be some kind of change in Jonas' behaviour too, although as for now I'm afraid there won't be.

As for chapter 20, there really is no love lost between Jonas and the two sisters, is there? Although Merry really seems to care about her sister's wounded feelings, she picks up being engaged to Jonas quickly enough, and she plays along with his teasing and his physically handling her easily enough too. Cherry, I think is more wounded in her pride because she misunderstood Jonas' intentions than she was wounded in her love for him. But that can also be my interpretation, because I cannot imagine someone falling in love with a miser like that.

Jantine wrote: "As a reader, I find Gamp very funny! I did think a couple of times, about what would it be like if you really need a nurse, and all you can afford is a woman who is always on the verge of being dru..."

Hi Jantine

I completely agree with you in your observations of the similarities between this novel and A Christmas Carol. Chronologically, MC and ACC are written rather concurrently. There is much residue that is sprinkled throughout ACC from MC.

I also think Dickens was accurate on his comments and irony concerning funerals. Jonas seems quite pleased with all the trappings and effort made in the preparations and procession of his father. I found the irony of the situation quite remarkable. No one comes to Anthony Chuzzlewit’s home to grieve. Then we read that Jonas was very conscious of how the funeral procession was perceived by the strangers that witnessed the street procession to the cemetery.

After the burial, Mrs Gamp goes home to her comforting bottle, Mr Mould enjoys a dinner with his family and what about Anthony Chuzzlewit? Well, after a rather long and exhausting chapter his burial and fate is dismissed with the last four words of the chapter “And that was all.” A sentence fragment lays to rest an exhausting chapter.

Hi Jantine

I completely agree with you in your observations of the similarities between this novel and A Christmas Carol. Chronologically, MC and ACC are written rather concurrently. There is much residue that is sprinkled throughout ACC from MC.

I also think Dickens was accurate on his comments and irony concerning funerals. Jonas seems quite pleased with all the trappings and effort made in the preparations and procession of his father. I found the irony of the situation quite remarkable. No one comes to Anthony Chuzzlewit’s home to grieve. Then we read that Jonas was very conscious of how the funeral procession was perceived by the strangers that witnessed the street procession to the cemetery.

After the burial, Mrs Gamp goes home to her comforting bottle, Mr Mould enjoys a dinner with his family and what about Anthony Chuzzlewit? Well, after a rather long and exhausting chapter his burial and fate is dismissed with the last four words of the chapter “And that was all.” A sentence fragment lays to rest an exhausting chapter.

When I read these lines in Chapter 19 I found I had work to do. It is a comment made by Mr. Mould:

"I have orders, sir, to put on my whole establishment of mutes; and mutes come very dear, Mr. Pecksniff; not to mention their drink."

I guess mutes, whatever they are don't eat, only drink. I've read MC before and should probably remember what funeral mutes are, but since I don't I looked it up:

The mute’s job was to stand vigil outside the door of the deceased, then accompany the coffin. The main purpose of a funeral mute was to stand around at funerals with a sad, pathetic face. A symbolic protector of the deceased, the mute would usually stand near the door of the home or church. In Victorian times, mutes would wear somber clothing including black cloaks, top hats with trailing hatbands, and gloves. There are plenty of accounts of mutes in Britain by the 1700s, and by Dickens’s time their attendance at even relatively modest funerals was almost mandatory. They were a key part of the Victorians’ extravagant mourning rituals, which Dickens often savaged as pointlessly, and often ruinously, expensive.

Mutes died out in the 1880s/90s and were a memory by 1914. Dickens played his part in their demise, as did fashion. Victorian funeral etiquette was complex and constantly changing, as befitted a huge industry, which partly depended on status anxiety for the huge profits Dickens criticized. What did for them most of all, though, was becoming figures of fun – mournful and sober at the funeral, but often drunk shortly afterwards.

In Britain, most mutes were day-labourers, paid for each individual job. In one of the many yarns told about them, a mute doubled up as a waiter at the meal after one funeral. The deceased’s brother asked him to approach a gentleman at the head of the table to say he wished to take a glass of wine with him. So he instantly changed his demeanour from friendly waiter to mournful mute, went up to the man and quietly said: “Please, sir, the corpse’s brother would like to take a glass o’wine wi’ ye.”

What a strange tradition, but I suppose in this case they may have been the only people besides Chuffey there who did look sad, and as Peter said, he is criticized for it.

"I have orders, sir, to put on my whole establishment of mutes; and mutes come very dear, Mr. Pecksniff; not to mention their drink."

I guess mutes, whatever they are don't eat, only drink. I've read MC before and should probably remember what funeral mutes are, but since I don't I looked it up:

The mute’s job was to stand vigil outside the door of the deceased, then accompany the coffin. The main purpose of a funeral mute was to stand around at funerals with a sad, pathetic face. A symbolic protector of the deceased, the mute would usually stand near the door of the home or church. In Victorian times, mutes would wear somber clothing including black cloaks, top hats with trailing hatbands, and gloves. There are plenty of accounts of mutes in Britain by the 1700s, and by Dickens’s time their attendance at even relatively modest funerals was almost mandatory. They were a key part of the Victorians’ extravagant mourning rituals, which Dickens often savaged as pointlessly, and often ruinously, expensive.

Mutes died out in the 1880s/90s and were a memory by 1914. Dickens played his part in their demise, as did fashion. Victorian funeral etiquette was complex and constantly changing, as befitted a huge industry, which partly depended on status anxiety for the huge profits Dickens criticized. What did for them most of all, though, was becoming figures of fun – mournful and sober at the funeral, but often drunk shortly afterwards.

In Britain, most mutes were day-labourers, paid for each individual job. In one of the many yarns told about them, a mute doubled up as a waiter at the meal after one funeral. The deceased’s brother asked him to approach a gentleman at the head of the table to say he wished to take a glass of wine with him. So he instantly changed his demeanour from friendly waiter to mournful mute, went up to the man and quietly said: “Please, sir, the corpse’s brother would like to take a glass o’wine wi’ ye.”

What a strange tradition, but I suppose in this case they may have been the only people besides Chuffey there who did look sad, and as Peter said, he is criticized for it.

And now I have to look up another thing going on during this strange, costly funeral. We're told:

"In short, the whole of that strange week was a round of dismal joviality and grim enjoyment; and every one, except poor Chuffey, who came within the shadow of Anthony Chuzzlewit's grave, feasted like a Ghoul."

Now a ghoul was always similar to a ghost to me, and I'm pretty sure a ghost has no reason to eat anything, so I need to find out what or why a ghoul is feasting and found this:

A Ghoal kills without thought, mutilates the corpse, and dines on it either by drinking the blood or eating the flesh. While they are more frequently associated with corpses, they are known to feed on human children, infants, and occasionally weak and sickened adults. Ghouls usually live near graveyards and in lonely places where they can safely feed on the deceased and for attacking and feasting on an unsuspecting traveler."

So there you go. I'd be careful if I were you walking alone at night, and I'd keep away from cemeteries. And we probably should be cremated. :-)

"In short, the whole of that strange week was a round of dismal joviality and grim enjoyment; and every one, except poor Chuffey, who came within the shadow of Anthony Chuzzlewit's grave, feasted like a Ghoul."

Now a ghoul was always similar to a ghost to me, and I'm pretty sure a ghost has no reason to eat anything, so I need to find out what or why a ghoul is feasting and found this:

A Ghoal kills without thought, mutilates the corpse, and dines on it either by drinking the blood or eating the flesh. While they are more frequently associated with corpses, they are known to feed on human children, infants, and occasionally weak and sickened adults. Ghouls usually live near graveyards and in lonely places where they can safely feed on the deceased and for attacking and feasting on an unsuspecting traveler."

So there you go. I'd be careful if I were you walking alone at night, and I'd keep away from cemeteries. And we probably should be cremated. :-)

I have a family story for you that came to me while I read this conversation between Jonas and his father in Chapter 18:

‘What a cold spring it is!’ whimpered old Anthony, drawing near the evening fire, ‘It was a warmer season, sure, when I was young!’

‘You needn’t go scorching your clothes into holes, whether it was or not,’ observed the amiable Jonas, raising his eyes from yesterday’s newspaper, ‘Broadcloth ain’t so cheap as that comes to.’

‘A good lad!’ cried the father, breathing on his cold hands, and feebly chafing them against each other. ‘A prudent lad! He never delivered himself up to the vanities of dress. No, no!’

‘I don’t know but I would, though, mind you, if I could do it for nothing,’ said his son, as he resumed the paper.

‘Ah!’ chuckled the old man. ‘if, indeed!—But it’s very cold.’

‘Let the fire be!’ cried Mr Jonas, stopping his honoured parent’s hand in the use of the poker. ‘Do you mean to come to want in your old age, that you take to wasting now?’

A few years ago we had a heat wave here, day after day it was so very hot, over 90 degrees that's 32 to you Tristram (I think). So I went out to my dad's place to check on him because I knew when I had been there a few days before he still hadn't put his air conditioner in the window even though I begged him to. So now I was worried about him being out there in this horrible heat with no way to cool off. But that's not what happened. When I walked in the door there he sat in his favorite chair with an electric heater in front of him turned on and a blanket over his legs. I told him he was crazy, he told me I was ornery, I asked him if I should make him something to eat, all I'd have to do was throw something on a plate and it would be cooked before I walked back to him and he told me to go home. I told him I refuse to go home, but I was going to go outside and check his garden where it would be cooler. It was. I was out there pulling weeds and it was still cooler than the house.

‘What a cold spring it is!’ whimpered old Anthony, drawing near the evening fire, ‘It was a warmer season, sure, when I was young!’

‘You needn’t go scorching your clothes into holes, whether it was or not,’ observed the amiable Jonas, raising his eyes from yesterday’s newspaper, ‘Broadcloth ain’t so cheap as that comes to.’

‘A good lad!’ cried the father, breathing on his cold hands, and feebly chafing them against each other. ‘A prudent lad! He never delivered himself up to the vanities of dress. No, no!’

‘I don’t know but I would, though, mind you, if I could do it for nothing,’ said his son, as he resumed the paper.

‘Ah!’ chuckled the old man. ‘if, indeed!—But it’s very cold.’

‘Let the fire be!’ cried Mr Jonas, stopping his honoured parent’s hand in the use of the poker. ‘Do you mean to come to want in your old age, that you take to wasting now?’

A few years ago we had a heat wave here, day after day it was so very hot, over 90 degrees that's 32 to you Tristram (I think). So I went out to my dad's place to check on him because I knew when I had been there a few days before he still hadn't put his air conditioner in the window even though I begged him to. So now I was worried about him being out there in this horrible heat with no way to cool off. But that's not what happened. When I walked in the door there he sat in his favorite chair with an electric heater in front of him turned on and a blanket over his legs. I told him he was crazy, he told me I was ornery, I asked him if I should make him something to eat, all I'd have to do was throw something on a plate and it would be cooked before I walked back to him and he told me to go home. I told him I refuse to go home, but I was going to go outside and check his garden where it would be cooler. It was. I was out there pulling weeds and it was still cooler than the house.

I still had questions at the end of Chapter 20 as to whether Merry actually accepted Jonas, but it appears that others believe she did. It did not seem clear to me. Now we have Martin, Sr. and Mary arriving and the chapter is over. It appears the next chapter leaves this as a cliffhanger and moves back to America which is very annoying to me. That is a pet peeve of mine.

I still had questions at the end of Chapter 20 as to whether Merry actually accepted Jonas, but it appears that others believe she did. It did not seem clear to me. Now we have Martin, Sr. and Mary arriving and the chapter is over. It appears the next chapter leaves this as a cliffhanger and moves back to America which is very annoying to me. That is a pet peeve of mine.

Kim wrote: "When I read these lines in Chapter 19 I found I had work to do. It is a comment made by Mr. Mould:

"I have orders, sir, to put on my whole establishment of mutes; and mutes come very dear, Mr. Pec..."

Dickens himself really disliked the idea of all the trappings and show that accompanied funerals. In his own will his wishes were explicit. He wanted a very quiet and private funeral. Such was not to be. His funeral became a period of mourning for the country and rather being interred in a country churchyard he was buried in Poet’s Corner of Westminster Abbey.

"I have orders, sir, to put on my whole establishment of mutes; and mutes come very dear, Mr. Pec..."

Dickens himself really disliked the idea of all the trappings and show that accompanied funerals. In his own will his wishes were explicit. He wanted a very quiet and private funeral. Such was not to be. His funeral became a period of mourning for the country and rather being interred in a country churchyard he was buried in Poet’s Corner of Westminster Abbey.

Bobbie wrote: "I still had questions at the end of Chapter 20 as to whether Merry actually accepted Jonas, but it appears that others believe she did. It did not seem clear to me. Now we have Martin, Sr. and Mary..."

Hi Bobbie

I’m glad I’m not the only one who had to dig around a bit. First, I found the death of Anthony Chuzzlewit was not stated in a very clear way (at least to me).

Next, we get the verbal fencing of Merry and Jonas. If two people have ever been portrayed as incompatible in literature this is the couple. Still, by the end of the chapter they are engaged. I don’t think their marriage will lead to much, but with Dickens we never know. We will see.

So far in this novel we have had a death that was less than obvious and a proposal that was obscure. What’s next?

Hi Bobbie

I’m glad I’m not the only one who had to dig around a bit. First, I found the death of Anthony Chuzzlewit was not stated in a very clear way (at least to me).

Next, we get the verbal fencing of Merry and Jonas. If two people have ever been portrayed as incompatible in literature this is the couple. Still, by the end of the chapter they are engaged. I don’t think their marriage will lead to much, but with Dickens we never know. We will see.

So far in this novel we have had a death that was less than obvious and a proposal that was obscure. What’s next?

Chapter 18

Chapter 18-- Oh, yeah, Pecksniff, Anthony, and Jonas all in one room. Pray for a gas leak.

-- Anthony has a live one for a son, hasn't he? A rabid dog.

-- Pecksniff lets Anthony talk about his daughter in this way, doesn't even feign insult.

-- One less Chuzzlewit to deal with. That's what happens when one speaks badly of charity and mercy. Virtue rules.

-- Jonas is impatient to take over the family money -- er, uhm -- business. I'm sure people know this and given Jonas's temper, they might conclude 2 + 2 = 4. He should worry.

Peter wrote: "Bobbie wrote: "I still had questions at the end of Chapter 20 as to whether Merry actually accepted Jonas, but it appears that others believe she did. It did not seem clear to me. Now we have Martin, Sr. and Mary..."

Peter wrote: "Bobbie wrote: "I still had questions at the end of Chapter 20 as to whether Merry actually accepted Jonas, but it appears that others believe she did. It did not seem clear to me. Now we have Martin, Sr. and Mary..."Hi Bobbie

I’m glad I’m not the only one who had to dig around a bit. First, I found the death of Anthony Chuzzlewit was not stated in a very clear way (at least to me)."

Yes, I also read the end of the chapter about 3 times trying to figure out whether Anthony was dead or not. Very confusing. And I guess we're just supposed to take Anthony's word for it that he and Merry are engaged now: "That's as good... as saying it right out." Well, I guess so, if your standards are low.

I do wonder if Jonas's choice of Merry over Cherry is a little tiny stirring of humanity in him, as it seems to be based on attraction rather than calculation. Anthony seems to hint to Pecksniff that Cherry would be a good fit because she'll be just as good a miser over Anthony's wealth passed down to Jonas as Jonas would. She does seem to be the better wifely candidate as far as avarice goes, so I'm a bit surprised to see Jonas choose differently.

But I *don't* think he's getting a Dolly Varden. Dolly would never sorta-agree to marry someone "that I might hate and tease you all my life." That's just weird.

Like a number of people, I was also getting Christmas Carol vibes here, especially with Jonas sitting around as uneasy about Anthony's ghost as Scrooge becomes about Marley's.

Is anyone else concerned that if fate doesn't intervene, Tom Pinch will end up like Chuffey, devoted past the grave to an undeserving master?

Is anyone else concerned that if fate doesn't intervene, Tom Pinch will end up like Chuffey, devoted past the grave to an undeserving master?And here I thought I had no affection for Tom Pinch.

Julie wrote: "Is anyone else concerned that if fate doesn't intervene, Tom Pinch will end up like Chuffey, devoted past the grave to an undeserving master?

And here I thought I had no affection for Tom Pinch."

Julie

Oh, I hope not. I like Tom Pinch. Yes, he is too passive and more than a touch too accommodating to Pecksniff. Tom does, however, have a good heart and I believe his musical talent is evidence of some level and form of passion.

I hope Tom never turns into a younger version of old Chuffey. The thought that Tom would always live under the shadow of Pecksniff is

an unsettling thought.

And here I thought I had no affection for Tom Pinch."

Julie

Oh, I hope not. I like Tom Pinch. Yes, he is too passive and more than a touch too accommodating to Pecksniff. Tom does, however, have a good heart and I believe his musical talent is evidence of some level and form of passion.

I hope Tom never turns into a younger version of old Chuffey. The thought that Tom would always live under the shadow of Pecksniff is

an unsettling thought.

Chapter 19

Chapter 19-- Jonas is more concerned about appearances than I thought he would be. In fact, up until now I haven't seen him care about appearances at all. Makes me wonder if there isn't more to his concern about what people might say about his father's death than just talk.

-- Did I get that right? The bird shop is next to the cats' meat house? Not a feather wasted, not a transportation expense acquired.

-- Mrs. Gap had a face for all occasions. Her morning countenance.

-- Chuffey's devotion to Anthony makes me wonder if there weren't some impurities, like decency and friendship, that snuck into Anthony's Chuzzlewit line. What did Anthony do to earn such devotion? What would Guy Fawkes say? What would Hugo Weaving say?

-- Mr. Mould, the undertaker. Hahahaha

-- Mr.s Mould's chief mourner. Hahahaha

Peter wrote: "Julie wrote: "Is anyone else concerned that if fate doesn't intervene, Tom Pinch will end up like Chuffey, devoted past the grave to an undeserving master?

Peter wrote: "Julie wrote: "Is anyone else concerned that if fate doesn't intervene, Tom Pinch will end up like Chuffey, devoted past the grave to an undeserving master?And here I thought I had no affection fo..."

Oh, I agree, Peter. I like Tom Pinch.

I like Tom Pinch too, and really hope he'll not become another Chuffey.

And yes, the engagement is so ... weird. I do not think Jonas did it out of emotion though. He has been asking Pecksniff about which daughter is a better wife, which one he likes best etc. so often, combined with asking 1000 pound of dowry more (which is a huge, huge amount of money in this time), I think he planned for this all along. Choosing the 'less wise' option to get more money out of his marriage, emotions have nothing to do with that, apart from playing those of others.

And Jonas caring for what others think ... I believe that he tries to placate certain people, to make sure there will be no investigation into his conduct because he was too loveless. I wouldn't be surprised if he'd poisoned Anthony somehow.

And yes, the engagement is so ... weird. I do not think Jonas did it out of emotion though. He has been asking Pecksniff about which daughter is a better wife, which one he likes best etc. so often, combined with asking 1000 pound of dowry more (which is a huge, huge amount of money in this time), I think he planned for this all along. Choosing the 'less wise' option to get more money out of his marriage, emotions have nothing to do with that, apart from playing those of others.

And Jonas caring for what others think ... I believe that he tries to placate certain people, to make sure there will be no investigation into his conduct because he was too loveless. I wouldn't be surprised if he'd poisoned Anthony somehow.

So many interesting comments here! I think that by now, the novel has got a little bit into shape and is taking a certain direction: Jonas and Martin are two young men who represent the next generation of the Chuzzlewit family, and it's going to be interesting to see how they will develop.

I liked the way old Anthony's death was described and think, like Peter said, there was something Shakespearean about the whole scene. Old Martin said that his wealth, instead of making him happy, created a hell on earth for him in that it made everyone around him expectant of receiving something from him and thus made him doubt any kind of interest, kindness and sympathy shown towards him: Were these not clever stratagems of greedy and scheming relatives who wanted to ingratiate themselves with him? Martin's distrust may have been based on experience but in the end it turned him into a cynic and someone who shuns the world, and who probably is a little bit egocentric at that. With regard to his brother, however, the dictum that money is the root of all evil is definitely true. What did that money buy old Anthony? Nothing but a son who is impatient to see his father die and who treats him roughly and without respect, probably in order to precipitate the desired event! Anthony is the best example of a man who used his money the wrong way.

And still, there is some ray of light in the darkness of Anthony's character for he must have been kind towards Chuffey in his way for otherwise the clerk would not hold him in such warm memory. In his perverted outlook on wealth and on economy, he praises Jonas whenever this young man shows his uncouth stinginess and mean shrewdness by pointing out, "Your own son, sir!" Chuffey does mean this a praise, but there is dramatic irony in this praise because to the reader, this weird encomium reads as, "You must reap what you have sown, and you have sown the seeds for an unloving son."

Like many here, I have the feeling that Anthony might also have been poisoned by Jonas because the son is far too eager to have Pecksniff there as a witness lest people should start rumouring. Where there's smoke, there's fire, is a German saying. All this funereal pomp is the crying out of Jonas's bad conscience, or rather - for he doesn't have much of a conscience - of his fear of people's opinion. In a way, the length of the funeral description seems justified to me - and is highly entertaining because of Mr. Mould's exertions to look grieved despite the continuous ring of the cash register - because it is another take on the novel's theme of hypocrisy.

I liked the way old Anthony's death was described and think, like Peter said, there was something Shakespearean about the whole scene. Old Martin said that his wealth, instead of making him happy, created a hell on earth for him in that it made everyone around him expectant of receiving something from him and thus made him doubt any kind of interest, kindness and sympathy shown towards him: Were these not clever stratagems of greedy and scheming relatives who wanted to ingratiate themselves with him? Martin's distrust may have been based on experience but in the end it turned him into a cynic and someone who shuns the world, and who probably is a little bit egocentric at that. With regard to his brother, however, the dictum that money is the root of all evil is definitely true. What did that money buy old Anthony? Nothing but a son who is impatient to see his father die and who treats him roughly and without respect, probably in order to precipitate the desired event! Anthony is the best example of a man who used his money the wrong way.

And still, there is some ray of light in the darkness of Anthony's character for he must have been kind towards Chuffey in his way for otherwise the clerk would not hold him in such warm memory. In his perverted outlook on wealth and on economy, he praises Jonas whenever this young man shows his uncouth stinginess and mean shrewdness by pointing out, "Your own son, sir!" Chuffey does mean this a praise, but there is dramatic irony in this praise because to the reader, this weird encomium reads as, "You must reap what you have sown, and you have sown the seeds for an unloving son."

Like many here, I have the feeling that Anthony might also have been poisoned by Jonas because the son is far too eager to have Pecksniff there as a witness lest people should start rumouring. Where there's smoke, there's fire, is a German saying. All this funereal pomp is the crying out of Jonas's bad conscience, or rather - for he doesn't have much of a conscience - of his fear of people's opinion. In a way, the length of the funeral description seems justified to me - and is highly entertaining because of Mr. Mould's exertions to look grieved despite the continuous ring of the cash register - because it is another take on the novel's theme of hypocrisy.

Yes, Peter, Mrs. Gamp is definitely a favourite of mine, maybe even the favourite Dickens character with me. And yes, Jantine, she is quite a sad person, if you take a closer look at her.

Her having a face for every occasion is probably another instance of hypocrisy, but I'd rather put it into the Todgers category and not into Mr. Pecksniff's. After all, Mrs. Gamp must earn a living and therefore she must be as ready to go to a birth as to a funeral. She has not much choice since life has not bedded her on roses. From her own words we learn that her husband died, and the narrator adds that she bore it admirably, from which we may infer that their marriage was not exactly a happy one. We don't know yet if they had any children, but she is a widow and must fend for herself, and she does so in the same spirit of determination as Mrs. Todgers, although Mrs. Gamp also show signs of other spirits as well.

Here's to Mrs. Gamp!

Her having a face for every occasion is probably another instance of hypocrisy, but I'd rather put it into the Todgers category and not into Mr. Pecksniff's. After all, Mrs. Gamp must earn a living and therefore she must be as ready to go to a birth as to a funeral. She has not much choice since life has not bedded her on roses. From her own words we learn that her husband died, and the narrator adds that she bore it admirably, from which we may infer that their marriage was not exactly a happy one. We don't know yet if they had any children, but she is a widow and must fend for herself, and she does so in the same spirit of determination as Mrs. Todgers, although Mrs. Gamp also show signs of other spirits as well.

Here's to Mrs. Gamp!

Why does Jonas take Merry instead of Cherry? Probably because she is the more lively, the more beautiful one, and all these are qualities that Jonas lacks and that might fascinate him. There might also be a darker impulse in him, namely that of getting the woman who held him in so much disdain, and on punishing her for it.

Tristram wrote: "In a way, the length of the funeral description seems justified to me - and is highly entertaining because of Mr. Mould's exertions to look grieved despite the continuous ring of the cash register - because it is another take on the novel's theme of hypocrisy."

Tristram wrote: "In a way, the length of the funeral description seems justified to me - and is highly entertaining because of Mr. Mould's exertions to look grieved despite the continuous ring of the cash register - because it is another take on the novel's theme of hypocrisy."I did enjoy Gamp and Mould's professional discussion of what people spend on births vs. funerals.

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "Chapter 19

-- Jonas is more concerned about appearances than I thought he would be. In fact, up until now I haven't seen him care about appearances at all. Makes me wonder if there isn't more to h..."

Xan

You ask a question that I am still wrestling with in the novel. Chuffey does have a devotion to Anthony Chuzzlewit. Why? Does it mean that Anthony was once a much more likeable person? If so, however, how do we account for the friction between Anthony and old Martin Chuzzlewit? Is the Anthony - Chuffey connection some version of the Pecksniff - Pinch relationship/attachment?

Somehow I get the feeling that Chuffey is a more independent person than the degrading treatment Pinch suffers from Pecksniff.

-- Jonas is more concerned about appearances than I thought he would be. In fact, up until now I haven't seen him care about appearances at all. Makes me wonder if there isn't more to h..."

Xan

You ask a question that I am still wrestling with in the novel. Chuffey does have a devotion to Anthony Chuzzlewit. Why? Does it mean that Anthony was once a much more likeable person? If so, however, how do we account for the friction between Anthony and old Martin Chuzzlewit? Is the Anthony - Chuffey connection some version of the Pecksniff - Pinch relationship/attachment?

Somehow I get the feeling that Chuffey is a more independent person than the degrading treatment Pinch suffers from Pecksniff.

Yes, now you name it, I do have that feeling too. Chuffy's doing with numbers also seems to indicate that he was very, very good at them, and in that way he might have been invaluable to Anthony, hence Anthony probably was kind to him, because he realized Chuffy brought him much more money with his head for numbers than he would ever cost even in his old age. Something Jonas might not realize, because he is more familiar with the old Chuffy who cannot do as much anymore. Also, this might be why Chuffy liked Anthony so much - he got the chance to do what he did best and liked best, and was hold in regard for it too. I think.

I still think the marriage was mostly a plan to gain more money and as much money as possible to Jonas. Fascination and punishment towards Merry might also be a reason though, indeed. He seems to make a game out of it. I still do not believe it was because he liked her in any way. He looks for a marriage, preferrably one with a dowry and as high a dowry as possible, and he plays his cards in a way that he wins this and gains something interesting as a plus.

I still think the marriage was mostly a plan to gain more money and as much money as possible to Jonas. Fascination and punishment towards Merry might also be a reason though, indeed. He seems to make a game out of it. I still do not believe it was because he liked her in any way. He looks for a marriage, preferrably one with a dowry and as high a dowry as possible, and he plays his cards in a way that he wins this and gains something interesting as a plus.

chapter 20

chapter 20-- I almost spilled my coffee over the keyboard when Jonas told Pecksniff he'd probably been prepared for a long time for someone to ask him for Charity's hand in marriage.

-- Too bad they hadn't completed the marriage negotiations a few days earlier. They could have married at the funeral and saved money. And think of the statement they would have made.

-- I must say, Charity is being quite uncharitable about the recent turn of events, while Mercy is flustered at the thought of being at Jonas's mercy. I would be too. But the question is, will both sisters continue to show charity and mercy towards one another, or is this the end of virtue as we know it.

-- I think we know very well why Jonas asked Mercy instead of Charity. He thinks he will get an additional 1,000 shillings out of it.

-- Things are looking up. Conflict. Combat??? Old Martin and Mary knocking on the door with Jonas on the other side. If old Martin disowned young Martin, a far better man than Jonas, for proposing to Mary, I dare not think what old Martin might do upon seeing Jonas when the door opens.

I had this awful thought. What if Jonas pursues Mary? I mean Jonas has to be thinking of all the money Old Martin has. I ask you, is there no justice and decency in the world?

I had this awful thought. What if Jonas pursues Mary? I mean Jonas has to be thinking of all the money Old Martin has. I ask you, is there no justice and decency in the world?

Peter wrote: "From Pecksniff’s point of view, what benefit would it be to marry Cherry, his favourite daughter, off to Jonas Chuzzlewit?"

Peter wrote: "From Pecksniff’s point of view, what benefit would it be to marry Cherry, his favourite daughter, off to Jonas Chuzzlewit?"I suspect Pecksniff and Jonas are playing one another. Pecksniff thinks Jonas likes Charity. By pretending Charity is his favorite, Pecksniff expects Jonas to accept a smaller dowry than he otherwise would to get Pecksniff to give up his favorite daughter.

Jonas plays this against Pecksniff. He immediately asks Mercy to marry him and demands another thousand from Pecksniff for not taking his favorite daughter from him.

I don't believe Pecksniff has a favorite daughter. And I don't believe Jonas is capable of caring for either daughter. He's coy about his intentions with Charity and Mercy because he sees a profit in both of them, but doesn't yet know (until now) which one is more profitable.

Ah, I just read Jantine's thoughts on Jonas picking Mercy. A lot like my own. Glad to see I'm not the only one who thinks the only preference at play here is money.

Ah, I just read Jantine's thoughts on Jonas picking Mercy. A lot like my own. Glad to see I'm not the only one who thinks the only preference at play here is money.I also wonder if Jonas, upon seeing Mary and thinking she will inherit Old Martin's money, will drop Mercy like a sack of potatoes and start wooing Mary. He has an out. Mercy never truly accepted his proposal.

Peter wrote: "Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "Chapter 19

Peter wrote: "Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "Chapter 19-- Jonas is more concerned about appearances than I thought he would be. In fact, up until now I haven't seen him care about appearances at all. Makes me wonde..."

There is a hint, if I'm remembering correctly, that Chuffey and Anthony go way back and are good friends. Maybe Anthony is like Scrooge without the benefit of ghosts to show him his erring ways. Like Scrooge he may have been at one time, when much younger, a charitable person. But age and money can be sclerotic. He is certainly not that now.

Julie wrote: "Is anyone else concerned that if fate doesn't intervene, Tom Pinch will end up like Chuffey, devoted past the grave to an undeserving master?

Julie wrote: "Is anyone else concerned that if fate doesn't intervene, Tom Pinch will end up like Chuffey, devoted past the grave to an undeserving master?And here I thought I had no affection for Tom Pinch."

I wonder this, too. but Dickens has made Tom a very good organ player, an I wonder how this may play out. Did churches pay organ players back them? Did they get paid a fee for playing at weddings and funerals? Just wondering out loud if the organ might lead Tom to freedom and independence. More than once it has been said how good he is at playing the organ.

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "Julie wrote: "Is anyone else concerned that if fate doesn't intervene, Tom Pinch will end up like Chuffey, devoted past the grave to an undeserving master?

And here I thought I had no affection fo..."

Xan

I’m not sure how much or even if church organ players (in small rural churches) were paid.

I look upon Tom’s organ playing as an indication of his kindness and creativity. I see his going to the church to play as a means of him finding solace and contentment away from the negativity and debasement of his character that he has been receiving from Pecksniff for years. Tom retreats into music in order to express himself. That he is attracted to Mary also signals to me that he has passion. Curse that Pecksniff. He seems to enjoy debasing Tom.

And here I thought I had no affection fo..."

Xan

I’m not sure how much or even if church organ players (in small rural churches) were paid.

I look upon Tom’s organ playing as an indication of his kindness and creativity. I see his going to the church to play as a means of him finding solace and contentment away from the negativity and debasement of his character that he has been receiving from Pecksniff for years. Tom retreats into music in order to express himself. That he is attracted to Mary also signals to me that he has passion. Curse that Pecksniff. He seems to enjoy debasing Tom.

Jantine wrote: "I still think the marriage was mostly a plan to gain more money and as much money as possible to Jonas. Fascination and punishment towards Merry might also be a reason though, indeed. He seems to make a game out of it. I still do not believe it was because he liked her in any way. He looks for a marriage, preferrably one with a dowry and as high a dowry as possible, and he plays his cards in a way that he wins this and gains something interesting as a plus."

Yes, it's quite clever how Jonas makes Pecksniff increase his dowry for Mercy by insisting that since it would be more difficult for him to part with Cherry, he could add some additional 1,000 pounds now that he can keep his favourite daughter. Maybe, Jonas planned that all along ...

Yes, it's quite clever how Jonas makes Pecksniff increase his dowry for Mercy by insisting that since it would be more difficult for him to part with Cherry, he could add some additional 1,000 pounds now that he can keep his favourite daughter. Maybe, Jonas planned that all along ...

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "I had this awful thought. What if Jonas pursues Mary? I mean Jonas has to be thinking of all the money Old Martin has. I ask you, is there no justice and decency in the world?"

Hmm, but would it not be quite obvious for Jonas that this is a very risky game? The Chuzzlewits, when they met at Mr. Pecksniff's earlier in the novel, all hated Mary because they suspected her of legacy-hunting, but by now should it not be clear to Jonas and Pecksniff that Mary is not to expect anything from the old man's will?

Hmm, but would it not be quite obvious for Jonas that this is a very risky game? The Chuzzlewits, when they met at Mr. Pecksniff's earlier in the novel, all hated Mary because they suspected her of legacy-hunting, but by now should it not be clear to Jonas and Pecksniff that Mary is not to expect anything from the old man's will?

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "I don't believe Pecksniff has a favorite daughter. And I don't believe Jonas is capable of caring for either daughter. He's coy about his intentions with Charity and Mercy because he sees a profit in both of them, but doesn't yet know (until now) which one is more profitable."

You're right, a man like Pecksniff probably does not like either of his daugthers too much and so is ready to bait fish, big fish, with them.

As to Chuffey and Anthony, I don't see why there might not have been genuine friendship between the two men. Just because a man is a skinflint and a greedy money-guzzler, this doesn't mean that he cannot be friends with another person. I find the characters in this novel quite complex, at least some of them, and no longer Quilpish, i.e. acting like villains in a Punch and Judy show. - Even Jonas's behaviour after his father's death, which runs counter to his stereotypical money-grabbing, is believable and shows us that he is also able to feel guilty - well, it's a possible interpretation - of wishing for his father's death, but still wishing for it while feeling guilty. There's much complexity in these characters.

You're right, a man like Pecksniff probably does not like either of his daugthers too much and so is ready to bait fish, big fish, with them.

As to Chuffey and Anthony, I don't see why there might not have been genuine friendship between the two men. Just because a man is a skinflint and a greedy money-guzzler, this doesn't mean that he cannot be friends with another person. I find the characters in this novel quite complex, at least some of them, and no longer Quilpish, i.e. acting like villains in a Punch and Judy show. - Even Jonas's behaviour after his father's death, which runs counter to his stereotypical money-grabbing, is believable and shows us that he is also able to feel guilty - well, it's a possible interpretation - of wishing for his father's death, but still wishing for it while feeling guilty. There's much complexity in these characters.

Pecksniff knows that, or at least he was told that, but I doubt he has told Jonas. And if Jonas has murdered his father, as some here believe, then he is not risk averse.

Pecksniff knows that, or at least he was told that, but I doubt he has told Jonas. And if Jonas has murdered his father, as some here believe, then he is not risk averse.Whoops! This was in response the Tristram's last post.

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "Pecksniff knows that, or at least he was told that, but I doubt he has told Jonas. And if Jonas has murdered his father, as some here believe, then he is not risk averse."

These are good points, Xan. Let's see how the plot is going to develop. And yes, I wonder if and how Jonas has murdered his father. He's the type of guy that would use poison.

These are good points, Xan. Let's see how the plot is going to develop. And yes, I wonder if and how Jonas has murdered his father. He's the type of guy that would use poison.

He very much is the type, yes. And I hadn't thought about what Xan mentions, about Jonas possibly believing Mary would be an even better match. The coming week we've all American chapters, while I like the goings on in England so much better, it's mean! I want to know what happens back home!

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "-- Too bad they hadn't completed the marriage negotiations a few days earlier. They could have married at the funeral and saved money. And think of the statement they would have made.."

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "-- Too bad they hadn't completed the marriage negotiations a few days earlier. They could have married at the funeral and saved money. And think of the statement they would have made.."OK, that's funny.

Tristram wrote: "Why does Jonas take Merry instead of Cherry? Probably because she is the more lively, the more beautiful one, and all these are qualities that Jonas lacks and that might fascinate him. There might ..."

I agree. Especially with the punishing her part, I think that's what he is doing, or planning to.

I agree. Especially with the punishing her part, I think that's what he is doing, or planning to.

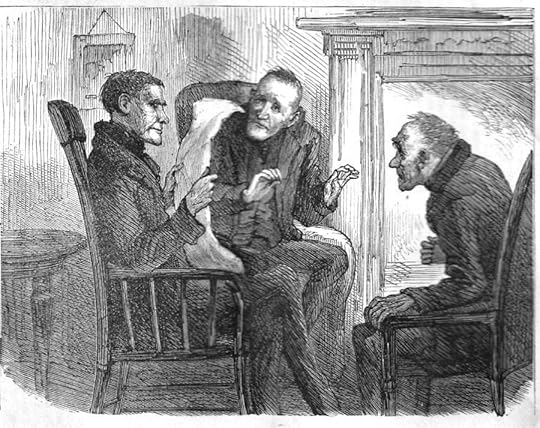

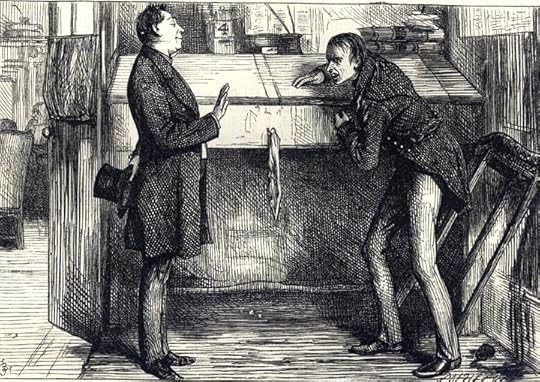

Jonas looks as old as his father or Chuffey in this illustration, I think so anyway:

The Dissolution of a Partnership

Chapter 18

Phiz

Text Illustrated: (there is a question mark after that)

It would have been, if it had made the noise which startled them; but another kind of time-piece was fast running down, and from that the sound proceeded. A scream from Chuffey, rendered a hundred times more loud and formidable by his silent habits, made the house ring from roof to cellar; and, looking round, they saw Anthony Chuzzlewit extended on the floor, with the old clerk upon his knees beside him.

He had fallen from his chair in a fit, and lay there, battling for each gasp of breath, with every shrivelled vein and sinew starting in its place, as if it were bent on bearing witness to his age, and sternly pleading with Nature against his recovery. It was frightful to see how the principle of life, shut up within his withered frame, fought like a strong devil, mad to be released, and rent its ancient prison-house. A young man in the fullness of his vigour, struggling with so much strength of desperation, would have been a dismal sight; but an old, old, shrunken body, endowed with preternatural might, and giving the lie in every motion of its every limb and joint to its enfeebled aspect, was a hideous spectacle indeed.

Commentary:

What is not present or shown can sometimes be as significant as what the careful illustrator chooses to include. In this instance, Old Chuffey rather than Jonas attends Anthony, who has suddenly collapsed on the floor of what appears to be the Chuzzlewit counting-house, if one may judge by the four ledgers sitting on Chuffey's desk, upper right. In the second illustration for the eighth monthly instalment, Pecksniff appears again, in part as a consequence of the first illustration as the family require a nurse for Chuffey, who is prostrate with grief at his old master's passing, which is signified in the initial August 1843 plate by the hands of the clock set at about five minutes after midnight. If we do not take the clock literally, however, then the scene depicted may be that in which the dying merchant interrupts the family's breakfast the next morning and is attended specifically by Chuffey rather than a vague "they" which probably indicates both Pecksniff and Jonas. The scene at the end of the chapter is therefore climactic, its title a suitable commentary on the strained relationship between Jonas and Anthony Chuzzlewit:

Mr. Pecksniff promised that he would remain, if circumstances should render it, in his esteemed friend’s opinion, desirable; they were finishing their meal in silence, when suddenly an apparition stood before them, so ghastly to the view that Jonas shrieked aloud, and both recoiled in horror.

Old Anthony, dressed in his usual clothes, was in the room — beside the table. He leaned upon the shoulder of his solitary friend; and on his livid face, and on his horny hands, and in his glassy eyes, and traced by an eternal finger in the very drops of sweat upon his brow, was one word — Death.

He spoke to them — in something of his own voice too, but sharpened and made hollow, like a dead man's face. What he would have said, God knows. He seemed to utter words, but they were such as man had never heard. And this was the most fearful circumstance of all, to see him standing there, gabbling in an unearthly tongue.

"He's better now," said Chuffey. "Better now. Let him sit in his old chair, and he'll be well again. I told him not to mind. I said so, yesterday."

They put him in his easy-chair, and wheeled it near the window; then, swinging open the door, exposed him to the free current of morning air. But not all the air that is, nor all the winds that ever blew 'twixt Heaven and Earth, could have brought new life to him.