The Old Curiosity Club discussion

Martin Chuzzlewit

>

MC, Chp. 36-38

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

Chapter 37

We’re still with Tom here, who has lost his way in London. He will probably consider himself very lucky for all that, since none of his nightmares about London – e.g. the danger of ending up in a pie – has come true. As yet.

He finds himself near the Monument, and considers asking the right way of the Man in the Monument, i.e. the man who collects the fee from those who are willing to climb all the steps inside the column in order to reach the platform and survey the city. When Tom finds that the Man in the Monument, after charging a couple their fee, turns to him and laughingly says that they don’t know how many steps they have to take and that it would have been worth twice the money to stay where they were, Tom considers the Man too cynical to be trusted.

QUESTION

Again, we are meant to realize that Tom, having lost faith in Pecksniff, looks at people with more suspicious eyes now. He was reminded of Pecksniff’s treacherousness when facing Ruth’s employers, and now the Man in the Monument’s cynical attitude also fills him with doubts. Is Tom growing up, or is he becoming a cynic himself? A little later in the chapter, the narrator states, for instance, ”An uneasy thought entered Tom’s head; a shadowy misgiving that the altered relations between himself and Pecksniff were somehow to involve an altered knowledge on his part of other people, and were to give him an insight into much of which he had had no previous suspicion.”

Suddenly, Tom hears a well-known voice behind him, and lo! ‘tis no other but Charity Pecksniff who welcomes him. She asks whether her father has already married and evinces signs of distrust of Mary Graham’s inclination to lure her father into matrimony. When Tom says that Mary is far from wishing to be married with Pecksniff, Charity tells him that he knows little about the wiles of women in that respect. When Tom asks her if she is married, she shows some traces of pleased embarrassment. Answering another of Tom’s questions, she makes it clear that she wants to stay in London and has no intention of going home:

Charity then asks Tom to come with her to Mrs. Todgers’s, which is nearby, from where Mr. Moddle – she makes a great deal of mysterious fuss about Mr. Moddle – can take him to Furnival’s Inn, but one of her major motives for taking him to see Mrs. Todgers is the fact that her sister Merry happens to be there. Indeed, she is a regular visitor to the place now. Tom suspects ulterior motives in Charity’s desire of his being re-introduced to Merry, an encounter he is not particularly partial to in the light of his memories of the scornful treatment he received by Merry. Indeed, the narrator lets us in on the fact that Charity wants Tom to witness Merry in her humiliation and pain because he already witnessed certain scenes at the Pecksniffs’ in which Charity was humiliated by Jonas and Merry.

Tom does not take long, though, to see that Merry is completely altered – that she is much more serious, thoughtful and … sad, and regardless of all the animosity the young woman showed him in her father’s house, his heart swells up with genuine pity. At first, Merry tries to keep up the appearances of old by speaking in her old manner, but when she realizes how kind Tom is, she drops her mask and when her sister has left the room to enquire after Mr. Moddle, she even tells Tom that she would like him to tell Mr. Chuzzlewit – provided he ever saw him again – that now she bears in mind what he told her by the churchyard, and that a little bit of more perseverance on his part might have made her change her mind at that time. So that, if ever again he comes into a similar situation, she would like him to be more pertinacious in his endeavours.

Later, Tom also finds that Mrs. Todgers feel really sympathetic with Merry, and this knowledge makes Tom find a lot of beauty in Mrs. Todgers. The narrator remarks,

QUESTIONS

What do you think of auctorial comments of the kind above?

Both Merry and Tom have changed in the course of the novel: In what ways are their developments similar, in what ways are there differences?

Do you think Merry’s change believable? How else could she have reacted to her new situation in life? Remember that Mrs. Todgers makes a point of saying that Merry never actually complains of her situation as Jonas’s wife.

Tom sees that Mrs. Todgers ”was poor, and that this good had sprung up in her from among the sordid strivings of her life”. In what way is Mrs. Todgers different from and similar to Mrs. Gamp?

While you are still reflecting on these questions, Miss Charity has managed to hunt up Mr. Moddle, and the dear Augustus conducts Mr. Pinch home, impressing him with exclamations like, ”’[…] YOU care what becomes of you? […] I don’t […] The Elements may have me when they please. I’m ready.’” Ahhh, the lucky bridegroom!

When Tom finally arrives at John Westlock’s place, he finds that his friend had been worrying about him – after an absence of quite some hours! – and when he explains to John what has meanwhile taken place, he finds John puzzled but eventually willing to accept Tom’s establishing himself and Islington, and even willing to come to see him for dinner the next day. When he later catches a glimpse of Ruth’s kissing Tom, John thinks that he would not be disinclined to change places with his friend.

We’re still with Tom here, who has lost his way in London. He will probably consider himself very lucky for all that, since none of his nightmares about London – e.g. the danger of ending up in a pie – has come true. As yet.

He finds himself near the Monument, and considers asking the right way of the Man in the Monument, i.e. the man who collects the fee from those who are willing to climb all the steps inside the column in order to reach the platform and survey the city. When Tom finds that the Man in the Monument, after charging a couple their fee, turns to him and laughingly says that they don’t know how many steps they have to take and that it would have been worth twice the money to stay where they were, Tom considers the Man too cynical to be trusted.

QUESTION

Again, we are meant to realize that Tom, having lost faith in Pecksniff, looks at people with more suspicious eyes now. He was reminded of Pecksniff’s treacherousness when facing Ruth’s employers, and now the Man in the Monument’s cynical attitude also fills him with doubts. Is Tom growing up, or is he becoming a cynic himself? A little later in the chapter, the narrator states, for instance, ”An uneasy thought entered Tom’s head; a shadowy misgiving that the altered relations between himself and Pecksniff were somehow to involve an altered knowledge on his part of other people, and were to give him an insight into much of which he had had no previous suspicion.”

Suddenly, Tom hears a well-known voice behind him, and lo! ‘tis no other but Charity Pecksniff who welcomes him. She asks whether her father has already married and evinces signs of distrust of Mary Graham’s inclination to lure her father into matrimony. When Tom says that Mary is far from wishing to be married with Pecksniff, Charity tells him that he knows little about the wiles of women in that respect. When Tom asks her if she is married, she shows some traces of pleased embarrassment. Answering another of Tom’s questions, she makes it clear that she wants to stay in London and has no intention of going home:

”’No, thank you. No! A mother-in-law who is younger than – I mean to say, who is as nearly as possible about the same age as one’s self, would not quite suit my spirit. Not quite!’ said Cherry, with a spiteful shiver.”

Charity then asks Tom to come with her to Mrs. Todgers’s, which is nearby, from where Mr. Moddle – she makes a great deal of mysterious fuss about Mr. Moddle – can take him to Furnival’s Inn, but one of her major motives for taking him to see Mrs. Todgers is the fact that her sister Merry happens to be there. Indeed, she is a regular visitor to the place now. Tom suspects ulterior motives in Charity’s desire of his being re-introduced to Merry, an encounter he is not particularly partial to in the light of his memories of the scornful treatment he received by Merry. Indeed, the narrator lets us in on the fact that Charity wants Tom to witness Merry in her humiliation and pain because he already witnessed certain scenes at the Pecksniffs’ in which Charity was humiliated by Jonas and Merry.

Tom does not take long, though, to see that Merry is completely altered – that she is much more serious, thoughtful and … sad, and regardless of all the animosity the young woman showed him in her father’s house, his heart swells up with genuine pity. At first, Merry tries to keep up the appearances of old by speaking in her old manner, but when she realizes how kind Tom is, she drops her mask and when her sister has left the room to enquire after Mr. Moddle, she even tells Tom that she would like him to tell Mr. Chuzzlewit – provided he ever saw him again – that now she bears in mind what he told her by the churchyard, and that a little bit of more perseverance on his part might have made her change her mind at that time. So that, if ever again he comes into a similar situation, she would like him to be more pertinacious in his endeavours.

Later, Tom also finds that Mrs. Todgers feel really sympathetic with Merry, and this knowledge makes Tom find a lot of beauty in Mrs. Todgers. The narrator remarks,

”Commercial gentlemen and gravy had tried Mrs Todgers’s temper; the main chance — it was such a very small one in her case, that she might have been excused for looking sharp after it, lest it should entirely vanish from her sight — had taken a firm hold on Mrs Todgers’s attention. But in some odd nook in Mrs Todgers’s breast, up a great many steps, and in a corner easy to be overlooked, there was a secret door, with ‘Woman’ written on the spring, which, at a touch from Mercy’s hand, had flown wide open, and admitted her for shelter.”

QUESTIONS

What do you think of auctorial comments of the kind above?

Both Merry and Tom have changed in the course of the novel: In what ways are their developments similar, in what ways are there differences?

Do you think Merry’s change believable? How else could she have reacted to her new situation in life? Remember that Mrs. Todgers makes a point of saying that Merry never actually complains of her situation as Jonas’s wife.

Tom sees that Mrs. Todgers ”was poor, and that this good had sprung up in her from among the sordid strivings of her life”. In what way is Mrs. Todgers different from and similar to Mrs. Gamp?

While you are still reflecting on these questions, Miss Charity has managed to hunt up Mr. Moddle, and the dear Augustus conducts Mr. Pinch home, impressing him with exclamations like, ”’[…] YOU care what becomes of you? […] I don’t […] The Elements may have me when they please. I’m ready.’” Ahhh, the lucky bridegroom!

When Tom finally arrives at John Westlock’s place, he finds that his friend had been worrying about him – after an absence of quite some hours! – and when he explains to John what has meanwhile taken place, he finds John puzzled but eventually willing to accept Tom’s establishing himself and Islington, and even willing to come to see him for dinner the next day. When he later catches a glimpse of Ruth’s kissing Tom, John thinks that he would not be disinclined to change places with his friend.

Chapter 38

When Tom and Mr. Moddle make their way towards Furnival’s Inn, they brush shoulders with Mr. Nadgett, who does not pay much attention to this encounter. But although neither of the man knows the other, both, Tom and Nadgett, have the same man on their mind at the moment – namely, Jonas Chuzzlewit. Mr. Nadgett has spent the past months keeping tabs on Jonas, observing his every move both private and public. We learn that Mr. Nadgett has even fallen in with Mr. Tacker, the chief mute, and with Mr. Mould, and he also insisted on seeing Dr. Jobling on the grounds that he did not feel very well in his liver. The doctor examined Nadgett and could not see any cause for his feeling unwell, but Nadgett insisted that he did not feel very well, pointing out that, after all, it was his and not the doctor’s liver, and so he should know best. Nadgett also acquires the habit of having a shave at Mr. Sweedlepipe’s and having a chat with Mrs. Gamp now and then.

All this was previous to the day when Tom brushes past Nadgett, and now this secret agent is on his way to Mr. Montague’s in order to make a report on his secret research. His secretive manners, which he does not even relinquish in the presence of his employer are quite annoying to that gentleman, but Montague knows that Nadgett is worth his hire and so he puts up with the man’s quirks, one of which is that he does not talk about the secrets he found out – for fear of being overheard – but that he wants Mr. Montague to read all his memoranda. At first, Montague goes through this procedure unwillingly and reluctantly, but very soon he becomes an avid reader. He casts upon Nadgett looks of wonder and also of alarm – one may interpret the alarm in various ways, I’m sure. Montague finishes his perusal of the papers by expressing his warmest thanks and admiration towards Nadgett – and then who should arrive but the subject of their research himself: Jonas Chuzzlewit.

Montague is very anxious for Nadgett to remain in the same room with him when receiving Jonas, and his face is pale and he casts suspicious looks at his razors while waiting for Jonas. When Jonas enters, he tells Montague in his old ungracious way that he is not at all satisfied with how things are running because he finds it very difficult to lay his hands on his share of the plunder. He even voices the suspicion that what with Montague’s privileges and the lack of control, it should be very easy for him to one day abscond with all the money if it pleases him. And all this will not do for Jonas, and he won’t have it! Suddenly, however, Montague puts his cards on the table – although, regrettably, not to us so that we are still kept in the dark – and he blackmails Jonas into talking Pecksniff into investing his money in the Anglo-Bengalee. The secret must be a terrible one, judging from Jonas’s reaction:

QUESTIONS

In the whole chapter, we never really learn what Montague holds over Jonas’s head, but it must be something very terrible. Any ideas?

How could Nadgett have got at the secret – whatever it is? It is implied that he learned it somehow from Jonas’s talking in his sleep because Montague keeps on talking about light sleepers who talk in their dreams. But who could have listened to Jonas’s talking in his dreams, and then told Nadgett?

Jonas is completely scornful of Nadgett, calling him a precious old dummy. As the last sentence of this chapter seems to imply, even after Montague discloses his knowledge of Jonas’s secret does Jonas not in any way connect Nadgett with this new state of affairs. – Why would a man like Jonas so direly fail to see a danger in Nadgett? And is there another “precious old dummy” Jonas probably underestimates?

And last, not least: Will any harm come of this to Pecksniff?

When Tom and Mr. Moddle make their way towards Furnival’s Inn, they brush shoulders with Mr. Nadgett, who does not pay much attention to this encounter. But although neither of the man knows the other, both, Tom and Nadgett, have the same man on their mind at the moment – namely, Jonas Chuzzlewit. Mr. Nadgett has spent the past months keeping tabs on Jonas, observing his every move both private and public. We learn that Mr. Nadgett has even fallen in with Mr. Tacker, the chief mute, and with Mr. Mould, and he also insisted on seeing Dr. Jobling on the grounds that he did not feel very well in his liver. The doctor examined Nadgett and could not see any cause for his feeling unwell, but Nadgett insisted that he did not feel very well, pointing out that, after all, it was his and not the doctor’s liver, and so he should know best. Nadgett also acquires the habit of having a shave at Mr. Sweedlepipe’s and having a chat with Mrs. Gamp now and then.

All this was previous to the day when Tom brushes past Nadgett, and now this secret agent is on his way to Mr. Montague’s in order to make a report on his secret research. His secretive manners, which he does not even relinquish in the presence of his employer are quite annoying to that gentleman, but Montague knows that Nadgett is worth his hire and so he puts up with the man’s quirks, one of which is that he does not talk about the secrets he found out – for fear of being overheard – but that he wants Mr. Montague to read all his memoranda. At first, Montague goes through this procedure unwillingly and reluctantly, but very soon he becomes an avid reader. He casts upon Nadgett looks of wonder and also of alarm – one may interpret the alarm in various ways, I’m sure. Montague finishes his perusal of the papers by expressing his warmest thanks and admiration towards Nadgett – and then who should arrive but the subject of their research himself: Jonas Chuzzlewit.

Montague is very anxious for Nadgett to remain in the same room with him when receiving Jonas, and his face is pale and he casts suspicious looks at his razors while waiting for Jonas. When Jonas enters, he tells Montague in his old ungracious way that he is not at all satisfied with how things are running because he finds it very difficult to lay his hands on his share of the plunder. He even voices the suspicion that what with Montague’s privileges and the lack of control, it should be very easy for him to one day abscond with all the money if it pleases him. And all this will not do for Jonas, and he won’t have it! Suddenly, however, Montague puts his cards on the table – although, regrettably, not to us so that we are still kept in the dark – and he blackmails Jonas into talking Pecksniff into investing his money in the Anglo-Bengalee. The secret must be a terrible one, judging from Jonas’s reaction:

”From red to white; from white to red again; from red to yellow; then to a cold, dull, awful, sweat–bedabbled blue. In that short whisper, all these changes fell upon the face of Jonas Chuzzlewit; and when at last he laid his hand upon the whisperer’s mouth, appalled, lest any syllable of what he said should reach the ears of the third person present, it was as bloodless and as heavy as the hand of Death.

He drew his chair away, and sat a spectacle of terror, misery, and rage. He was afraid to speak, or look, or move, or sit still. Abject, crouching, and miserable, he was a greater degradation to the form he bore, than if he had been a loathsome wound from head to heel.”

QUESTIONS

In the whole chapter, we never really learn what Montague holds over Jonas’s head, but it must be something very terrible. Any ideas?

How could Nadgett have got at the secret – whatever it is? It is implied that he learned it somehow from Jonas’s talking in his sleep because Montague keeps on talking about light sleepers who talk in their dreams. But who could have listened to Jonas’s talking in his dreams, and then told Nadgett?

Jonas is completely scornful of Nadgett, calling him a precious old dummy. As the last sentence of this chapter seems to imply, even after Montague discloses his knowledge of Jonas’s secret does Jonas not in any way connect Nadgett with this new state of affairs. – Why would a man like Jonas so direly fail to see a danger in Nadgett? And is there another “precious old dummy” Jonas probably underestimates?

And last, not least: Will any harm come of this to Pecksniff?

Tristram wrote: "Dear Curiosities,

First of all, let me wish a Happy New Year to all of you and express my hope that 2020 will be another year of interesting, thought-inspiring and fun-laden discussions on the Ini..."

There is certainly no place like London, Tristram, and I think Tom’s time in London will open up many more possibilities for our friend Tom. Tom’s strength of character is also Tom’s weakness of character. Tom is a kind trusting person. He seeks the best in people. From Mrs Lupin and the coach driver to the next stranger he will meet, Tom will see the best in others. Sadly, this has lead in the past to him being used, ignored, or seen as a dupe by others.

Combined, Tom and Mark Tapley give the novel characters who function as one extreme emotion, that of goodness and trust. This allows Dickens the opportunity to set other characters in opposition. The greedy, mean-spirited, and social misfits such as Jonas and Pecksniff are thus further highlighted as characters as well.

When Tom seeks out Westlake in this chapter we have a union of good characters. Next, Tom and Westlake seek out Ruth and convince her to leave her employment and take up residence with her brother. This event brings Ruth and John into contact which may well ignite an interesting relationship. Also, Dickens has now established two residences in London that are inhabited by good people. From this base, Dickens can launch his next focus on plot which will, no doubt, include many weird and wonderful characters and places in London.

First of all, let me wish a Happy New Year to all of you and express my hope that 2020 will be another year of interesting, thought-inspiring and fun-laden discussions on the Ini..."

There is certainly no place like London, Tristram, and I think Tom’s time in London will open up many more possibilities for our friend Tom. Tom’s strength of character is also Tom’s weakness of character. Tom is a kind trusting person. He seeks the best in people. From Mrs Lupin and the coach driver to the next stranger he will meet, Tom will see the best in others. Sadly, this has lead in the past to him being used, ignored, or seen as a dupe by others.

Combined, Tom and Mark Tapley give the novel characters who function as one extreme emotion, that of goodness and trust. This allows Dickens the opportunity to set other characters in opposition. The greedy, mean-spirited, and social misfits such as Jonas and Pecksniff are thus further highlighted as characters as well.

When Tom seeks out Westlake in this chapter we have a union of good characters. Next, Tom and Westlake seek out Ruth and convince her to leave her employment and take up residence with her brother. This event brings Ruth and John into contact which may well ignite an interesting relationship. Also, Dickens has now established two residences in London that are inhabited by good people. From this base, Dickens can launch his next focus on plot which will, no doubt, include many weird and wonderful characters and places in London.

Peter,

I agree when you point out that Tom's strength of character is also his weakness of character: A man who follows his principles - as when he stands in for his sister when she is bullied by her employer's family - will often find himself worse off afterwards, as Tom does when he suddenly has to provide for his sister, and not only for himself. But then, typically, Tom only sees the positive side of this new state of affairs - namely that he is now allowed to spend most of his time with Ruth.

Simultaneously, Tom's weakness of character is also his strength, as it appears to me: Why, for instance, does the coachman very soon feel friendly towards Tom? I'd say this is because Tom is ready to share his provision hamper with him (when Pecksniff and Jonas and Martin, too, would have eaten it on their own). Why did Mrs. Lupin give him such a hamper (and an unasked-for loan) in the first place? Well, because he was always kind and helpful and never asked for a return. In the long run, Tom's example seems to say, kindness is rewarded (to avoid saying "pays", which might sound rather materialistic and selfish). Only someone who is thoroughly rotten, like Pecksniff, will have it in their hearts to exploit Tom, whereas someone who is just like the average man, like the coachman, will feel inclined to act on friendly and fair terms with Tom.

I may not be too overtly Tom-friendly (because his naivety annoys me), but I will give Tom this any time.

I agree when you point out that Tom's strength of character is also his weakness of character: A man who follows his principles - as when he stands in for his sister when she is bullied by her employer's family - will often find himself worse off afterwards, as Tom does when he suddenly has to provide for his sister, and not only for himself. But then, typically, Tom only sees the positive side of this new state of affairs - namely that he is now allowed to spend most of his time with Ruth.

Simultaneously, Tom's weakness of character is also his strength, as it appears to me: Why, for instance, does the coachman very soon feel friendly towards Tom? I'd say this is because Tom is ready to share his provision hamper with him (when Pecksniff and Jonas and Martin, too, would have eaten it on their own). Why did Mrs. Lupin give him such a hamper (and an unasked-for loan) in the first place? Well, because he was always kind and helpful and never asked for a return. In the long run, Tom's example seems to say, kindness is rewarded (to avoid saying "pays", which might sound rather materialistic and selfish). Only someone who is thoroughly rotten, like Pecksniff, will have it in their hearts to exploit Tom, whereas someone who is just like the average man, like the coachman, will feel inclined to act on friendly and fair terms with Tom.

I may not be too overtly Tom-friendly (because his naivety annoys me), but I will give Tom this any time.

Peter wrote: "When Tom seeks out Westlake in this chapter we have a union of good characters. Next, Tom and Westlake seek out Ruth and convince her to leave her employment and take up residence with her brother. This event brings Ruth and John into contact which may well ignite an interesting relationship. Also, Dickens has now established two residences in London that are inhabited by good people."

Although I see your point, this reunion of good characters worries me a bit, because from my experience, we are in for at least one chapter full of mawkish silliness, like describing the harmonious household of the Pinches. That's really Dickens's weak side, in my opinion: He has a penchant for slush.

Although I see your point, this reunion of good characters worries me a bit, because from my experience, we are in for at least one chapter full of mawkish silliness, like describing the harmonious household of the Pinches. That's really Dickens's weak side, in my opinion: He has a penchant for slush.

To me Tom is one of those people who will help people to the point of hurting himself. His self-preservation governor is broken. He makes lasting friendships, and people are drawn to him, want to like him. He's a friend in need, and many won't forget that. Tom will never be rich or well off, but neither will he go without. Those willing to lend him a hand in time of need are legion.

To me Tom is one of those people who will help people to the point of hurting himself. His self-preservation governor is broken. He makes lasting friendships, and people are drawn to him, want to like him. He's a friend in need, and many won't forget that. Tom will never be rich or well off, but neither will he go without. Those willing to lend him a hand in time of need are legion.

There certainly is no place like London. I liked the reference to Sweeney Todd to be honest. With The Christmas Tree we talked about ghost stories, but sometimes I also like a bit of dirty creepiness, and I love that Dickens weaves that into a chapter about Tom. It keeps that chapter from getting too sweetly good.

I also am very curious what Tiggs has hanging over Jonas' head. It cannot be his meanness, for everyone knows about that. It might be that Jonas (believes he) killed his father.

He somehow underestimates some elder people mostly. I think I saw you referencing to Chuffy, Tristran ;-) Who also might be the one telling about what Jonas says at night. I thought about Merry at first, but she's probably too scared of Jonas. Where I didn't like her at first, I notice that I now hope she'll soon be freed of the creep.

He somehow underestimates some elder people mostly. I think I saw you referencing to Chuffy, Tristran ;-) Who also might be the one telling about what Jonas says at night. I thought about Merry at first, but she's probably too scared of Jonas. Where I didn't like her at first, I notice that I now hope she'll soon be freed of the creep.

Tristram wrote: "Chapter 37

We’re still with Tom here, who has lost his way in London. He will probably consider himself very lucky for all that, since none of his nightmares about London – e.g. the danger of endi..."

Yes. This chapter presents us with the characters of Merry Pecksniff and Tom who have both been involved in life-altering situations and circumstances. Tom has been able to keep hold of the optimistic silver lining in his life but Merry has been defeated by her altered circumstances. I think this is due to the support group that each had gathered in their earlier lives. With the exception of Pecksniff, everyone was a friend of, or friendly towards Tom. Merry, on the other hand, had no such network of friends or family.

I think we also see in Mrs Todgers how a person with a good heart and a good soul will find others who will reciprocate that support, respect, and concern. It seems in this chapter that Dickens is beginning to align the characters into either supporting each other or being alienated through some form of trauma.

For instance, Moodle will continue to mourn the loss of Merry, regardless of the fact that Cherry is now interested in him. He is beyond redemption. As for Cherry, she has no allies and has attached herself and her hopes on Moodle. Cherry’s heavy-handed domination cannot lead to any good end. Therefore, both Moodle and Cherry are doomed to failure since they have no support group. The survivors, such as Ruth, Tom and Mrs Todgers will survive and perhaps even prosper.

Time will tell.

We’re still with Tom here, who has lost his way in London. He will probably consider himself very lucky for all that, since none of his nightmares about London – e.g. the danger of endi..."

Yes. This chapter presents us with the characters of Merry Pecksniff and Tom who have both been involved in life-altering situations and circumstances. Tom has been able to keep hold of the optimistic silver lining in his life but Merry has been defeated by her altered circumstances. I think this is due to the support group that each had gathered in their earlier lives. With the exception of Pecksniff, everyone was a friend of, or friendly towards Tom. Merry, on the other hand, had no such network of friends or family.

I think we also see in Mrs Todgers how a person with a good heart and a good soul will find others who will reciprocate that support, respect, and concern. It seems in this chapter that Dickens is beginning to align the characters into either supporting each other or being alienated through some form of trauma.

For instance, Moodle will continue to mourn the loss of Merry, regardless of the fact that Cherry is now interested in him. He is beyond redemption. As for Cherry, she has no allies and has attached herself and her hopes on Moodle. Cherry’s heavy-handed domination cannot lead to any good end. Therefore, both Moodle and Cherry are doomed to failure since they have no support group. The survivors, such as Ruth, Tom and Mrs Todgers will survive and perhaps even prosper.

Time will tell.

Tristram wrote: "Chapter 38

When Tom and Mr. Moddle make their way towards Furnival’s Inn, they brush shoulders with Mr. Nadgett, who does not pay much attention to this encounter. But although neither of the man ..."

I think it will be to Jonas’s own peril to take Nadgett too lightly. He is a shadowy figure, is very infrequently seen in his own residence, and has apparently been keeping his eye on Jonas for some time. It is evident that Jonas does not trust Montague, and equally obvious that Montague holds some knowledge that is not favourable to Jonas.

Montague’s rooms are like a den of thieves, and it seems that each of the thieves continue to size up and mistrust the others. Surely this cannot end well. That said, they may even end up with a close shave from Sweedlepipe in more ways than one.

When Tom and Mr. Moddle make their way towards Furnival’s Inn, they brush shoulders with Mr. Nadgett, who does not pay much attention to this encounter. But although neither of the man ..."

I think it will be to Jonas’s own peril to take Nadgett too lightly. He is a shadowy figure, is very infrequently seen in his own residence, and has apparently been keeping his eye on Jonas for some time. It is evident that Jonas does not trust Montague, and equally obvious that Montague holds some knowledge that is not favourable to Jonas.

Montague’s rooms are like a den of thieves, and it seems that each of the thieves continue to size up and mistrust the others. Surely this cannot end well. That said, they may even end up with a close shave from Sweedlepipe in more ways than one.

Peter wrote: "For instance, Moodle will continue to mourn the loss of Merry, regardless of the fact that Cherry is now interested in him."

You are right: Moodle could say that bygones are bygones and look into the future. Nevertheless, it would be a bad choice for him to team up with Charity, if you ask me, because it is all too obvious that Charity will be the only one to wear the nether garments in their relationship, and he will end up as a hen-pecked husband if he marries her. Apart from that, Moodle probably senses that she is not really interested in him as a Moodle with all his Moodlish qualities, but just as a husband. In other words, she has set her cap on him because he happens to be available, and maybe also because he is passive enough to play her game.

Coming to think of their relationship, maybe Moodle actually enjoys being miserable now that his hopes for Merry are crushed - and that he therefore takes some perverse delight in ruining his future life by marrying Cherry?

You are right: Moodle could say that bygones are bygones and look into the future. Nevertheless, it would be a bad choice for him to team up with Charity, if you ask me, because it is all too obvious that Charity will be the only one to wear the nether garments in their relationship, and he will end up as a hen-pecked husband if he marries her. Apart from that, Moodle probably senses that she is not really interested in him as a Moodle with all his Moodlish qualities, but just as a husband. In other words, she has set her cap on him because he happens to be available, and maybe also because he is passive enough to play her game.

Coming to think of their relationship, maybe Moodle actually enjoys being miserable now that his hopes for Merry are crushed - and that he therefore takes some perverse delight in ruining his future life by marrying Cherry?

I enjoyed this section of chapters especially when it looks like Jonas will get his comeuppance and hopefully Pecksniff as well. I am getting more interested as we go along and actually glad that we are getting to the end of the story. This one has been very long for me.

I enjoyed this section of chapters especially when it looks like Jonas will get his comeuppance and hopefully Pecksniff as well. I am getting more interested as we go along and actually glad that we are getting to the end of the story. This one has been very long for me.

Chapter 39

Chapter 39I like Tom when he's angry and morally outraged. All of a sudden he thinks quicker and shows excellent command of the language. All people act differently when incensed, but Tom turns into another person, an equal, a person I really like.

Another book I would have liked someone to have written is the Pinch's family story. What was Tom and Ruth's parents like? How did Tom and Ruth end up with the employers they ended up with, and what was their early training that turned them into the meek souls they are?

Yet Tom has a bit of the paladin in him. He's one of the more interesting characters. And why do I so often find Dickens' secondary characters more interesting than his primary characters?

Bobbie wrote: "I enjoyed this section of chapters especially when it looks like Jonas will get his comeuppance and hopefully Pecksniff as well. I am getting more interested as we go along and actually glad that w..."

Hi Bobbie

Yes. Finally the action and interconnections among the characters and various plots are beginning to come together. MC has been a long haul indeed.

Hi Bobbie

Yes. Finally the action and interconnections among the characters and various plots are beginning to come together. MC has been a long haul indeed.

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "Chapter 39

I like Tom when he's angry and morally outraged. All of a sudden he thinks quicker and shows excellent command of the language. All people act differently when incensed, but Tom turns i..."

Hi Xan

Tom Pinch is a favourite character for me too. Without giving any specific spoilers you may be glad to know that Tom will not fade away as the novel wraps up.

I agree with you about the secondary characters. My favourite secondary character is Mr Wemmick from Great Expectations. I would love to have learned more about the backstory of him and his aged parent.

I like Tom when he's angry and morally outraged. All of a sudden he thinks quicker and shows excellent command of the language. All people act differently when incensed, but Tom turns i..."

Hi Xan

Tom Pinch is a favourite character for me too. Without giving any specific spoilers you may be glad to know that Tom will not fade away as the novel wraps up.

I agree with you about the secondary characters. My favourite secondary character is Mr Wemmick from Great Expectations. I would love to have learned more about the backstory of him and his aged parent.

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "Tom will never be rich or well off, but neither will he go without. Those willing to lend him a hand in time of need are legion."

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "Tom will never be rich or well off, but neither will he go without. Those willing to lend him a hand in time of need are legion."Xan - your comments here made me think of George Bailey in "It's A Wonderful Life". Of course, Tom doesn't have the aspirations and ambitions that George Bailey had, but I think, like George, he's got no idea just how much he means to those around him. I think, also, of Mark Tapley and the family (and other passengers and crew) he befriended on the ship. Mark is a more worldly-wise version of Tom. He knows there's darkness lurking near the light, but he chooses to live in the light and, as Tristram put it, he's often rewarded for his friendship and kindness. Maybe the alternate title for this book should have been "It's a Jolly Life". :-)

Jantine wrote: I also like a bit of dirty creepiness, and I love that Dickens weaves that into a chapter about Tom. It keeps that chapter from getting too sweetly good.

Yes, I loved that too! And I'm proud of Tom for standing up to Ruth's employers and giving them hell... politely. I fear the pre-Pecksniff-revelation Tom might have had much less backbone. That, too, made what might have been a very saccharine chapter enjoyable.

Tristram wrote: ...she has set her cap on him because he happens to be available, and maybe also because he is passive enough to play her game.

I had some pity for Cherry and the manipulative way she was treated, but she has shown her true colors with Moodle, and now any pity has turned to dislike. She is with Moodle for two reasons, to punish him (and by extension, Jonah) for liking Merry instead of her, and to shove Merry's bad decision in her face. It's a heartless woman, indeed, who can see that her sister is being regularly abused, and still chooses to flaunt what might have been. Cherry is selfish to the core. Merry, though, also disappointed me in her initial treatment of Tom. I guess old habits die hard. There are chinks of redemption showing in Merry, but she's obviously not quite there yet.

Xan wrote: Another book I would have liked someone to have written is the Pinch's family story. ...

I think Tom and Ruth must have been distant cousins to Nicholas and Kate Nickleby. They are very much alike in my mind, except that Tom isn't hot-headed and impetuous, nor as condescending as Nicholas. Maybe it's his organ music that soothes his soul.

Chapters 37 & 38

Chapters 37 & 38I still think Charity has mettle in her, which I like. Of course, she doesn't always use it in the best of ways, but look who raised her.

Tom and the narrator sounding ominous about Mercy's future. Perhaps it's time for Cherry to show some charity towards her sister by wielding some of her mettle at Jonas. I think I know why Jonas didn't chose Cherry. Cherry would have shown him no mercy, might even have poked a hole in him with a parasol.

Ah, Mr. Montague. Was that this novel he was in? :-) It's been a while.

Looks like he's got the goods on Jonas. Was Jonas stupid enough to put his murderous intentions and desirers in some sort of correspondence? Charity would have owned him.

Could it be that Montague, Jonas, and Pecksniff all come tumbling down together? Could we be this lucky?

Aha!!! John sees Ruth and already he's thinking of (pork?) chops. Wedding bells are in the air.

With all the characters and subplots this thousand page book may not be long enough.

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "John sees Ruth and already he's thinking of (pork?) chops. Wedding bells are in the air...."

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "John sees Ruth and already he's thinking of (pork?) chops. Wedding bells are in the air...."My spit-take for the day. :-)

Wanted to say one more thing about Charity and her Muddlehead of a husband to be. If Muddlehead were to marry one of Dickens' sweet heroines or damsels in distress, it would be a disaster. No way this guy can carry the load for two.

Wanted to say one more thing about Charity and her Muddlehead of a husband to be. If Muddlehead were to marry one of Dickens' sweet heroines or damsels in distress, it would be a disaster. No way this guy can carry the load for two.On the other hand, Charity has the perfect personality to turn Muddlehead into some sort of success. He needs her more and she thinks she needs him. It's a marriage made in . . . well, not heaven . . . but together they make a better person than either do separately.

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: " If Muddlehead were to marry one of Dickens' sweet heroines or damsels in distress, it would be a disaster...."

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: " If Muddlehead were to marry one of Dickens' sweet heroines or damsels in distress, it would be a disaster...."Interesting supposition, Xan. Yes - it would be along the lines of Quilp marrying Nell, or if Madeline Bray had had to go through with her marriage to Arthur Gride, or - dare I say it? - if Mary should have to wed Pecksniff! It would be unthinkable! But Cherry isn't the ideal little homemaker, so Dickens allows her to be abused. I think the only time I can remember one of Dickens more idealized - but not "perfect", just a bit more sympathetic - female characters ending up with a brute was when Pet Meagles married Henry Gowan.

I don't like to try to analyze things too closely or attribute things to the author undeservedly, but it does make one wonder if Dickens isn't making the subtle statement that women who aren't Stepford Wives may just deserve a little "correction". Horrible thought, but it crossed my mind. Hard not to make the leap to poor Catherine, or even Maria Beadnell. He may not have laid a finger on Maria, but his pen gave her quite a lashing in the form of Flora Finching. I hate to even ask, but do we know if Dickens was ever physically abusive towards Catherine? Maybe I don't want to know. :-(

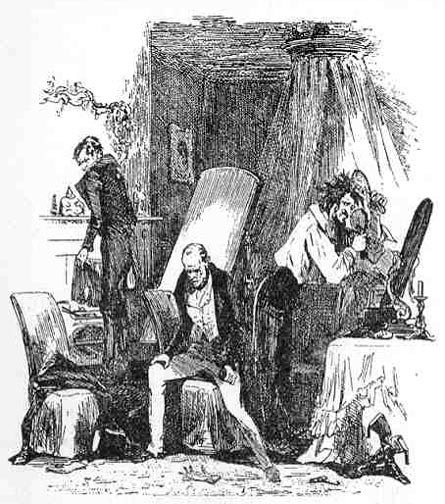

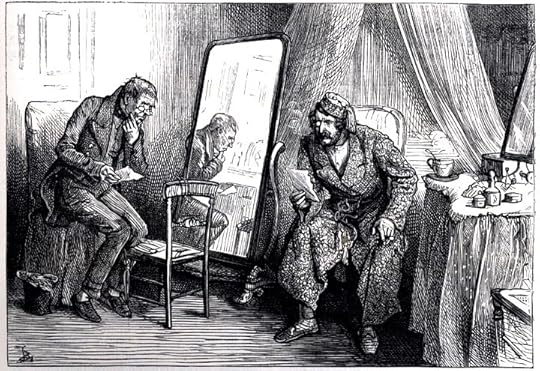

Mr. Nadgett breathes an atmosphere of mystery

Chapter 38

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

"Well! He’s not wanted here, I suppose," said Jonas. "He may go, mayn’t he?"

"Oh, let him stay, let him stay!" said Tigg. ‘He’s a mere piece of furniture. He has been making his report, and is waiting for further orders. He has been told," said Tigg, raising his voice, "not to lose sight of certain friends of ours, or to think that he has done with them by any means. He understands his business."

"He need," replied Jonas; "for of all the precious old dummies in appearance that I ever saw, he’s about the worst. He’s afraid of me, I think."

"It’s my belief," said Tigg, "that you are Poison to him. Nadgett! give me that towel!'"

Commentary: Jonas in a Vice

Careful study of the illustration and the chapter, however, reveals that the subject is not Nadgett but Jonas Chuzzlewit, caught in a vice being tightened by the inscrutable private detective (upper left) and the duplicitous financier (right), who have acquired intelligence against him that will enable them to plunder his hard-won inheritance or to bring him to justice. The text describes Tigg close to his uncomfortable business partner, speaking sotto voce as he describes his confidential agent as "a mere piece of furniture" before raising his voice so that Nadgett can hear his partial description of Nadgett's commission. In fact, the illustration synthesizes several moments in the chapter, rendering it a symbolic moment rather than a tableau vivant based on a single passage. Jonas's posture suggests the very point at which Tigg has just whispered the guilty secret in Jonas's ear, and Jonas in reflex “drew his chair away, and sat a spectacle of terror, misery and rage. He was afraid to speak, or look, or move, or sit still. Abject, crouching, and miserable, he was a greater degradation to the form he bore, than if he had been a loathsome wound from head to heel.”

Chapter 38 does not immediately reveal the secret that afflicts Phiz's central character, whom we recognize from previous illustrations such as "Mr. Jonas Chuzzlewit Entertains His Cousins" (Chapter 11, Part 5, May 1843). Readers, like Jonas himself, find themselves puzzled and, like Nadgett, must piece together visual and verbal clues. Appearances are deceptive here, for Nadgett, although merely glancing over his shoulder at Jonas, observes him closely and Tigg, cheerfully brushing his hair, has only moments before revealed his terror at the prospect of being left alone with his brutal and violent business associate whom he would seem to have at his mercy.

Having already appeared in such illustrations as Pleasant Little Family Party at Mr. Pecksniff's (Ch. 4), Martin Meets an Acquaintance at the House of a Mutual Relation (Ch. 13), and The Board (ch. 27) that together graph his rise from cadger and sponger to insurance magnate, the elegantly bewhiskered Montague Tigg (alias "Tigg Montague") is as familiar a figure at this point in Phiz's program as the lean and lanky Jonas. Up to this point, however, Nadgett, who has been at best a shadowy figure, has never once appeared in the narrative-pictorial sequence. Now, as the plot line involving Tigg the swindler and Jonas the murderer takes a sinister turn, Nadgett assumes a greater prominence in the text than in its visualization. With his back toward the viewer, Nadgett remains partially hidden, for we cannot read his face. From Chapter 27 Phiz and the serial reader would have recalled that Dickens had described Montague's private detective as "a short, dried-up, withered old man" with an intensely secretive manner and the uncanny ability to blend into his surroundings, seemingly "a mere piece of furniture" and "a dummy." Jonas mistakenly describes Nadgett as "afraid" of him, when in fact he should fear Nadgett. Now, by close observation of Jonas's movements, dogging his subject's footsteps, and making enquiries at Poll Sweedlepipe's and Mr. Mould's, Nadgett has uncovered Jonas's having attempted to poison his own father.

Since the thirty-eighth chapter begins with a long detailed description of Nadgett's actions, Phiz's title seems appropriate, but his intention upon further reflection seems to be to confuse or mislead readers. Already they, like Tigg, have learned of Nadgett's half-a-dozen "weighty" memoranda — but unlike Tigg readers remain in dark as to the precise contents of those memoranda other than that they bear "a deeper impression of Somebody's hoof." In order to heighten the suspense, Dickens, who has been careful not to reveal the contents of Nadgett's notes, has made Jonas's reactions show their importance. At the beginning of the scene in Tigg's dressing room, Jonas has just entered, Nadgett has retired to the stove which Tigg uses to heat his curling irons, and Tigg has suddenly begun to brush his unruly follicles vigorously. Jonas immediately asks Tigg to dismiss "old what's-his-name," but in vain. Although he reveals no anxiety in either the plate or the letterpress, Tigg is determined to retain Nagett as a witness and even a protector. Tigg's use of the word "Poison" (which Dickens has capitalized to imply the speaker's emphasizing the ominous word) seems to alarm Jonas. Whereas the text communicates Jonas's shock by the sudden pallor of his lips, the illustration suggests it by his rigid posture and his right hand's gripping his knee.

In the absence of much textual detail about Tigg's dressing room, other than the stove, curling tongs, and chairs, Phiz could improvise, particularly with respect to the cheval glass immediately behind Jonas and a symbolic object on the floor in front of him. Since Tigg is dressing, Phiz has shown his boots lying conspiratorially against one another (right) and his jacket strewn on a chair (left), and Tigg is concentrating on working the brushes against either side of his head. Meanwhile, as Nadgett observes Jonas over his shoulder as he dries his handkerchief in front of the stove, Tigg is apparently addressing Jonas as he examines his own countenance in the mirror on his dressing table. What then is lying at Jonas's feet?

Upon entering earlier, Nadgett had thrown his hat upon the floor and extracted his pocket-book in order to deliver his memoranda. Although Dickens does not so specify, Phiz has decided that Nadgett has thrown down his beaver glove, too, and that it should appear to have a life of its own since, according to Steig in Dickens and Phiz, it "appears to be reaching for [Jonas's] throat". What one might initially mistake for the feet of a dead rat lying on the carpet are in fact the bent fingers of the detective's glove, shaped by Nadgett's own and fulfilling his intention.

The slanted standing mirror both to alienates the seated Jonas from the two standing figures and highlights his inward gaze as he ponders the implications of what Jonas has just told him. The immobile image of Jonas Chuzzlewit, elsewhere so vigorous, works upon the viewer's imagination, underscoring a number of textual moments and synthesizing them. Rendered at least temporarily incapable of action and seemingly lost in thought, Jonas will soon enough take decisive action against the schemer who has attempted to entangle him in his web. Both text and image at this point make readers suspect that Jonas had poisoned his father. Trapped like a rat, he may well be contemplating how to extricate himself from his adversary's snare. The thirty- third illustration, "Mr. Jonas Exhibits His Presence of Mind" (chapter 52), therefore, is the natural extension of the thirtieth, as Jonas acts with force and determination to eliminate Tigg’s threat to his life and fortunes.

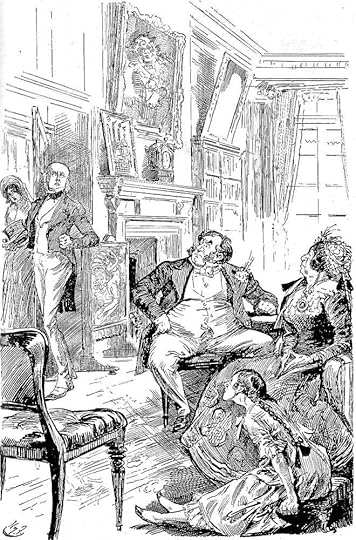

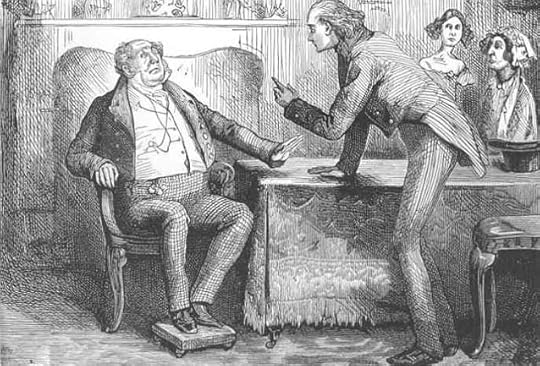

Tom Pinch at the brass and copper founder's

Chapter 36

Harry Furniss

Text illustrated:

"Pretty well! Upon my word," exclaimed the gentleman, "this is pretty well!"

"It is very ill, sir," said Tom. "It is very bad and mean, and wrong and cruel. Respect! I believe young people are quick enough to observe and imitate; and why or how should they respect whom no one else respects, and everybody slights? And very partial they must grow — oh, very partial! — to their studies, when they see to what a pass proficiency in those same tasks has brought their governess! Respect! Put anything the most deserving of respect before your daughters in the light in which you place her, and you will bring it down as low, no matter what it is!"

"You speak with extreme impertinence, young man," observed the gentleman.

"I speak without passion, but with extreme indignation and contempt for such a course of treatment, and for all who practise it," said Tom. "Why, how can you, as an honest gentleman, profess displeasure or surprise at your daughter telling my sister she is something beggarly and humble, when you are for ever telling her the same thing yourself in fifty plain, out-speaking ways, though not in words; and when your very porter and footman make the same delicate announcement to all comers? As to your suspicion and distrust of her: even of her word: if she is not above their reach, you have no right to employ her."

"No right!" cried the brass-and-copper founder.

"Distinctly not," Tom answered. "If you imagine that the payment of an annual sum of money gives it to you, you immensely exaggerate its power and value. Your money is the least part of your bargain in such a case. You may be punctual in that to half a second on the clock, and yet be Bankrupt. I have nothing more to say," said Tom, much flushed and flustered, now that it was over, "except to crave permission to stand in your garden until my sister is ready."

Not waiting to obtain it. Tom walked out.

Commentary: Tom Gives His Sister's Employer's Notice

The narrative now shifts to the aftermath of Pecksniff's discharging Tom Pinch, who sets out for London to find his sister, Ruth. She is a little younger than her brother, and works as a governess for the family of an industrialist in Camberwell, a new suburb south of the Thames suitable for such a wealthy, upper-middle class family. Treated with disrespect by her demanding employers, Ruth is delighted when her brother gives the brass-and-copper founder a piece of his mind — and her notice.

All this occurs while Martin and Mark complete their American adventure by returning from the malarial swamps of Eden, Tom Pinch sets out from the Wiltshire village where he has served as Pecksniff's architectural apprentice. His destination is theCamberwell district of Southwark, south of the Thames, where his sister, Ruth, is a governess to the daughters of a wealthy industrialist, although Furniss depicts but one child. Discovering that her sister's employers are verbally abusive, demeaning in their attitude towards her, and unreasonable in their demands upon his sister, this new, assertive Tom dares to give the captain of industry a piece of his mind, and then to serve notice on his sister's behalf. Together they leave the upper-middle-class mansion and take rooms in Islington, where Ruth becomes amodel housekeeper, and Tom finds unexpected employment as the organizer and cataloguerof a private library.

Although Fred Barnard in the Household Edition illustration "No right!" cried the brass-and-copper founder (see below), attempted to realize the scene in which Tom visits his sister at the comfortable, upper-middle-class suburb Camberwell and finds her much put-upon by her employer, Furniss's version is much more dramatic, owing to his foregrounding the nouveau-riche family and putting the departing Pinches in the background as Tom delivers a Parthian shot. Ironically, despite its dramatic potential, Dickens's original illustrator, Hablot Knight Browne, avoided the scene entirely,showing Tom's departure from Wiltshire by coach and then the Pinches in their Islington (then a village north of London proper) flat as John Westlock, formerly Tom's fellow apprentice and Ruth's future husband, pays an unexpected call.

In the Barnard illustration, Tom wags an admonitory finger in the face of the surprised, overfed bourgeois as the employer's ugly wife and daughter look on (right). In the background, the fireplace and bric-a-brac on the mantelpiece establish the setting as the family's parlour. In the 1910, illustration, however, Furniss gives the reader a "long shot" which reveals every indication of Victorian affluence: padded chairs, oil paintings (including a study of a smoke-spewing factory, and a likeness of the corpulent industrialist), an ornate clock, a well-stocked bookcase, a fabric fireplace screen (which bears the image of Pomona, Roman goddess of abundance, bearing a cornucopia of fruit and flowers), wainscoting, carpets, and floor-to-ceiling drapery. The painting or mirror perched atop the bookcase to the rear of what is probably the family's capacious parlour seems precariously balanced, as if it is about to fall, and the overall effect of the accumulated furnishings is somewhat unsettling, as if the emphasis on the acquisition of material possessions leaves little room for people. The founder's indignation and his wife's hauteur complement Tom's upright figure and determined departure, his closed fist indicative of self-control under emotionally trying circumstances. Ruth, concerned, looks on from the corridor. Furniss's handling of the materials given him by Barnard and Dickens is masterful in its multiple characterisations and critique of the late 19th c. nouveau riche.

At the brass and copper maker's

Chapter 36

Fred Barnard

Commentary:

While Martin and Mark complete their American adventure by returning from the malarial swamps of Eden, Tom Pinch sets out from the Wiltshire village where he has served as Pecksniff's architectural apprentice. His destination is the Camberwell district of Southwark, south of the Thames, where his sister, Ruth, is a governess to the daughters of a wealthy industrialist, although Furniss depicts but one child. Discovering that her sister's employers are verbally abusive, demeaning in their attitude towards her, and unreasonable in their demands upon his sister, this new, assertive Tom dares to give the captain of industry a piece of his mind, and then to serve notice on his sister's behalf. Together they leave the upper-middle-class mansion and take rooms in Islington, where Ruth becomes a model housekeeper, and Tom finds unexpected employment as the organizer and cataloguer of a private library.

Although Fred Barnard in the 1872 Household Edition illustration attempts to realize the scene in which Tom visits his sister at Camberwell and finds her much put-upon by her insufferably arrogant and small-minded employer, Harry Furniss's version is much more dramatic, owing to his foregrounding the nouveau-riche family and putting the departing Pinches in the background as Tom delivers a Parthian shot. Ironically, despite its dramatic potential, Dickens's original illustrator, Hablot Knight Browne, avoided the scene entirely, showing Tom's departure from Wiltshire by coach and then the Pinches in their Islington (village north of London) flat as John Westlock, formerly Tom's fellow apprentice and Ruth's future husband, pays an unexpected call. In the Barnard illustration, Tom wags an admonitory finger in the face of the surprised, overfed bourgeois as the employer's ugly wife and daughter look on (right). In the background, the fireplace, bric-a-brac on the mantelpiece, and richly embroidered tablecloth establish the setting as the family's parlour, and convey a sense of their shallow materialism. Clearly nobody has addressed the brass-and-copper founder in such critical terms as Barnard uses the occasion to demonstrate Tom's new-found assertiveness.

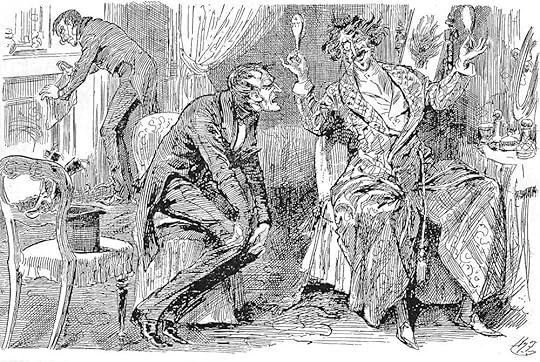

Jonas and Tigg

Chapter 38

Fred Barnard

Commentary:

Detective Nadgett makes his confidential report to Mr. Montague, formerly "Montague Tigg," in Ch. 38, "Secret Service," about Jonas Chuzzlewit's activities. Highly cautious and apprehensive about the possibility of being overheard, Nadgett insists on Montague's reading his multi-page account silently rather than have Nadgett deliver it orally. The highly ornate dressing-gown and cap which the affluent Tigg wears here are entirely Barnard's invention; in the February 1844 Hablot Knight Browne illustration, Tigg is in shirt-sleeves, preparing to get dressed to go the Anglo-Bengalee offices.

Jonas and Montague Tigg

Chapter 38

Harry Furniss

Text illustrated:

I am unfortunate to find you in this humour," said Tigg, with a remarkable kind of smile: "for I was going to propose to you — for your own advantage; solely for your own advantage — that you should venture a little more with us."

"Was you, by G —?" said Jonas, with a short laugh.

"Yes. And to suggest," pursued Montague, "that surely you have friends; indeed, I know you have; who would answer our purpose admirably, and whom we should be delighted to receive."

"How kind of you! You'd be delighted to receive 'em, would you?" said Jonas, bantering.

"I give you my sacred honour, quite transported. As your friends, observe!"

"Exactly," said Jonas; "as my friends, of course. You'll be very much delighted when you get 'em, I have no doubt. And it'll be all to my advantage, won't it?"

"It will be very much to your advantage," answered Montague, poising a brush in each hand, and looking steadily upon him. "It will be very much to your advantage, I assure you.

"And you can tell me how," said Jonas, "can't you?"

"Shall I tell you how?" returned the other.

Commentary: Miserable Jonas, Secretive Nadgett, and Merry Montague

The object of detective Nagett's investigations is not the large-scale swindler Montagu Tigg — the self-styled Director of the Anglo-Bengalee Disinterested Loan and Life Insurance Company — but the surly, avaricious Jonas Chuzzlewit. The passage describing his particular interest in Jonas faces the illustration in which Jonas almost snarls at the financier as Tigg (now, "Mr. Montagu") brushes his unruly hair while Mr. Nadgett warms himself by the fire in this lavishly decorated room that is an extension of Tigg's flamboyant personality. The hyperbolic figures of Jonas and Montague are Furniss's revisions of their less dramatic counterparts in the February 1844 serial illustration Mr. Nadgett Breathes, as Usual, an Atmosphere of Mystery in serial Part 14, Chapter 38 (see below), and elaborated by seventies illustrator Fred Barnard in the The Household Edition illustration Mr. Nadgett produces the result of his private enquiries (see below). The conversation between the swindler and the putative murderer in Chapter 38 might be better characterized as Jonas Chuzzlewit and Tigg Montague since the confidence man has now reversed his surname and his Christian name to start life over.

Over the course of a number of illustrated editions of The Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit (1844) one finds several representations of this crucial scene in the Jonas Chuzzlewit/Montague Tigg plot, Dickens's exposé on the life-insurance and investment sector, rampant with fraud and corporate collapses due to the nefarious activities of such confidence men as the chameleon-like indigent Montague Tigg who has transformed himself into a captain of industry, Tigg Montague. To assure himself of Jonas's compliance in his scheme to defraud thousands of investors, the Director of the Anglo-Bengalee has hired a private detective, convincingly realised by Sol Eytinge, Jr. in the 1867 Diamond Edition. Barnard in the 1872 transatlantic Household Editiondescribes the confidential meeting that precedes Tigg's blackmailing Jonas with the secret knowledge that he has poisoned his father in order to inherit the family business. The original illustration in the 1843-44 serial by Hablot Knight Browne shows a much deflated Jonas after Tigg has whispered the secret that would be Jonas's undoing, whereas Furniss has attempted to capture the moments just prior to the revelation. Nadgett in both the Phiz and Furniss plates keeps out of the way, but overhears everything that the pair say as he carefully observes the guilty partner's reaction.

The Furniss illustration juxtaposes the savage, angular Jonas in a business suit and the cheerful, self-confident Tigg in a floral dressing-gown. Whereas Jonas is downcast in the original Phiz steel-engraving for February 1844 as the tranquil Tigg, in shirt-sleeves, matter-of-factly brushes his hair before a mirror on his dresser; Jonas, meanwhile, has just learned what confidential information about him Tigg has acquired from his private detective, Nadgett (standing before the fireplace). Revising the Phiz original, Furniss moves the reader in for a close-up and sharpens the contrast between the principal figures, making Tigg ebullient as he sits (rather than stands) at his dressing-table, and Jonas angry as he sits, confronting him rather than turning away. The monocled financier sees right through the surly Jonas, knowing and exploiting his vulnerability. The confidence man here is about to spring his trap and bring Jonas firmly within his grip.

Kim wrote: "

Jonas and Montague Tigg

Chapter 38

Harry Furniss

Text illustrated:

I am unfortunate to find you in this humour," said Tigg, with a remarkable kind of smile: "for I was going to propose to yo..."

This Furniss illustration captures the moment and the characters perfectly.

Jonas and Montague Tigg

Chapter 38

Harry Furniss

Text illustrated:

I am unfortunate to find you in this humour," said Tigg, with a remarkable kind of smile: "for I was going to propose to yo..."

This Furniss illustration captures the moment and the characters perfectly.

It's so good to have the illustrations back, Kim! Thank you a lot for your trouble and your time. As usual, I am intrigued with Barnard's work - my copy of the book has the illustrations by Phiz, and so I know them pretty well -, and I especially like the idea that Barnard put Mr. Nadgett in front of a lifesize mirror. I am a film noir aficionado, and mirrors often play an important role in that genre. I think that the mirror here is a very clever hint at the fact that Mr. Nadgett usually keeps his own counsel and exclusively consorts with himself. He may even be of so intricate a mental state, always gleaning impressions and collecting information, that the mirror might have some right to imply that Mr. Nadgett even observes himself as an observer. Apart from that the mirror makes it possible that there are two Mr. Nadgetts in the room but only one Tigg Montague - some sign that, after all, Nadgett is a bit cleverer than his employer?

First of all, let me wish a Happy New Year to all of you and express my hope that 2020 will be another year of interesting, thought-inspiring and fun-laden discussions on the Inimitable and his works and everything coming into the ken and range thereof. I’m glad to see how this group is thriving and how we have acquired new active members.

Another person who is going to thrive soon is certainly our friend Tom Pinch, who is finally going to seek his own fortune, as we learn in the title of Chapter 36, which is devoted nearly entirely to Pecksniff’s ex-disciple and his arrival in London. We learn that although Tom still thinks Salisbury a wonderful city, full of overwhelming miracles, it nevertheless has lost its savour for him because of his disappointment in Pecksniff.

For all this bleakness, though, Tom has not lost faith in humankind in general, as the narrator is ready to point out when he says,

Consulting with his friend, the organist’s assistant, as to what would be the best course for him to adopt, he learns that he must go to London because there was no place like it, and since Tom couples the idea of London with thoughts of his sister and of John Westlock, decides to follow this advice and orders a place on the coach to London. He has to wait a day, however, the coach being already full, and despite the increased bill he would run up at his inn, this inspires him with a sense of adventure and holiday. At last, the day of departing comes, and he is seen off by Mrs. Lupin, who not only has brought him his luggage and forbidden her employee to look at Tom – because otherwise, Tom would have handed the man a tip –, but also prepared him a generous assortment of provisions for the road, including, as Tom is going to find out later, the loan of a 5 pound note. With his readiness to share his provisions with the coachman, whose neighbour he is for the journey, and the admiration that man cannot help expressing for Mrs. Lupin, whom he sees as on friendly terms with his new passenger, Tom does not fail to make friends with the coachman and pass a very pleasant journey. When they finally arrive in London, the coachman is very surprised to find that there is no one waiting for Tom because he thinks that such a capital fellow must of course be eagerly expected by those who know him.

QUESTIONS

In the first part of this chapter, there is virtually not a lot happening, but still the narrator uses it to give us an idea of Tom’s character and how it might have changed after his disappointment in Pecksniff. In what way could Tom’s behaviour have changed, and why did that not happen? After all, Tom says, on his journey, ”’[…] Upon my word, the kindness of people perfectly melts me.’” What would you regard as Tom’s strong side, and his weak one?

Tom has another very pleasant impression of the “kindness of people” when he pays a visit to his friend John shortly after his arrival in London. Westlock lives in Furnival’s Inn, enjoying the calm, but also the slight disorderliness of a bachelor’s existence, and he is ready to share his breakfast – or the various ingredients that could make one – as well as his lodgings with his old friend. In fact, he will not take no for an answer and says that he will also help Tom to gain a foothold in London. One of Tom’s fears was that as soon as John would hear that he has finally been undeceived as to Pecksniff’s true colours, he would gloat upon Tom and rub it in, but to his delight he sees that John is far from behaving so meanly and triumphantly. John even says that he doesn’t know whether he should be glad or sorry for Tom having made that discovery about Pecksniff which is so hurtful to him, and this decency on his friend’s part gives Tom pangs about ever having doubted John’s generosity of spirit.

Tom then has a look at the paper in order to get an idea of what positions are vacant and what kind of skills are needed in the capital, and what he reads soon fills him with a pessimistic outlook on human relations:

Before putting their heads together in earnest as to Tom’s future in London, however, both of the friends come to the conclusion that it would be best for Tom to pay his sister a visit, which Tom does accordingly. When he arrives at the mansion where his sister works, he is both appalled and stunned to find the domestics behave with such insolence towards him who comes to see Miss Pinch, and to Miss Pinch, implicitly. He then is called upon as a witness against his own sister by her employer, who charges her with not being able to command respect from his daughter and to teach her proper behaviour. The father and mother of that worthy pupil are disgusted with her having called a governess a poor beggarly thing, not so much taking umbrage at the insult as such as at the lowness of the expression, and they put the blame on Ruth. As regards his sister, however, Tom is not the placid and humble man as whom we have known him, because he is very proud of her and loves her very much. Plus, as the narrator indicates, he suspects that there may well be more Pecksniffs in the world but only one, and so he does not hesitate a second but immediately speaks up for his sister, saying that parents can hardly expect their children to show respect for someone they themselves treat with scorn and a lack of consideration. Tempers rise on both sides – Ruth, however, remains passive and is rather talked about than talking, being one of the genuine Dickens heroines –, and Tom tells his sister to pack up her things and leave her service immediately.

Later it occurs to him that now, of course, he cannot take up John’s offer since he is responsible for his sister, and he immediately starts looking for lodgings for himself and Ruth, choosing Islington as not too dear an area to live. After several hours, he has found a modest place in an old-fashioned house, and he and his sister start setting up their household by buying victuals and other needful things.

QUESTIONS

As I said, this is yet another Tom chapter, and apparently our narrator gets great pleasure from talking about Tom. What situations did you find most telling about Mr. Pinch? When were you surprised? Do you think that Tom and his sister justify such a detailed treatment, or would you rather have heard about other characters?