The Old Curiosity Club discussion

David Copperfield

>

DC, Chp. 13-15

In Chapter 14, we learn more about Mr. Dick’s story and we also witness an encounter between Aunt Betsey and the dreadful Murdstones, whose name sounds like Murderer to Aunt Betsey’s ears. This is what we learn about Mr. Dick:

”’I suppose,’ said my aunt, eyeing me as narrowly as she had eyed the needle in threading it, ‘you think Mr. Dick a short name, eh?’

‘I thought it was rather a short name, yesterday,’ I confessed.

‘You are not to suppose that he hasn’t got a longer name, if he chose to use it,’ said my aunt, with a loftier air. ‘Babley—Mr. Richard Babley—that's the gentleman's true name.’

I was going to suggest, with a modest sense of my youth and the familiarity I had been already guilty of, that I had better give him the full benefit of that name, when my aunt went on to say:

‘But don’t you call him by it, whatever you do. He can’t bear his name. That’s a peculiarity of his. Though I don't know that it’s much of a peculiarity, either; for he has been ill-used enough, by some that bear it, to have a mortal antipathy for it, Heaven knows. Mr. Dick is his name here, and everywhere else, now—if he ever went anywhere else, which he don’t. So take care, child, you don’t call him anything BUT Mr. Dick.’”

And also this:

”’He has been CALLED mad,’ said my aunt. ‘I have a selfish pleasure in saying he has been called mad, or I should not have had the benefit of his society and advice for these last ten years and upwards—in fact, ever since your sister, Betsey Trotwood, disappointed me.’

‘So long as that?’ I said.

‘And nice people they were, who had the audacity to call him mad,’ pursued my aunt. ‘Mr. Dick is a sort of distant connexion of mine—it doesn't matter how; I needn't enter into that. If it hadn't been for me, his own brother would have shut him up for life. That’s all.’

I am afraid it was hypocritical in me, but seeing that my aunt felt strongly on the subject, I tried to look as if I felt strongly too.

‘A proud fool!’ said my aunt. ‘Because his brother was a little eccentric—though he is not half so eccentric as a good many people—he didn't like to have him visible about his house, and sent him away to some private asylum-place: though he had been left to his particular care by their deceased father, who thought him almost a natural. And a wise man he must have been to think so! Mad himself, no doubt.’

Again, as my aunt looked quite convinced, I endeavoured to look quite convinced also.

‘So I stepped in,’ said my aunt, ‘and made him an offer. I said, ‘Your brother's sane—a great deal more sane than you are, or ever will be, it is to be hoped. Let him have his little income, and come and live with me. I am not afraid of him, I am not proud, I am ready to take care of him, and shall not ill-treat him as some people (besides the asylum-folks) have done.’ After a good deal of squabbling,’ said my aunt, ‘I got him; and he has been here ever since. He is the most friendly and amenable creature in existence; and as for advice!—But nobody knows what that man’s mind is, except myself.’”

This not only tells us a lot about Mr. Dick but also about Aunt Betsey: namely that behind her rough façade there is a lot of kindness, and likewise that she has a peculiar way of looking at things. Not quite unlike Mr. Peggotty, Aunt Betsey has established a patchwork family of her own – interestingly, not that it had anything to do with the novel, this is also a recurring motif in some of Clint Eastwood’s films, like in The Outlaw Josey Wales –, and it is also interesting that she started taking care of Mr. Dick about the same time she was disappointed with regard to the outcome of Clara Copperfield’s pregnancy. I think that Aunt Betsey’s motive may lie in the bad experience she had with her own marriage, which made her distrustful of men in general – there are abundant examples of her skeptical view on marriage in her talk – but could not stifle her desire for company around her. Interestingly, Mr. Dick is a fool in whose wisdom Aunt Betsey hold implicit trust, whereas this did not go for her nephew, David’s father, whose naivety she likes to expound on.

I also stumbled across this little sentence here: “’Be as like your sister as you can, and speak out!’” Will David from now on have to live with being constantly compared to a sister who does not even exist? Will Aunt Betsey eventually reconcile herself to David`s being a boy? Together with Steerforth, there are already two people now who regret that David has no sister.

I really enjoyed the way Aunt Betsey had it out with the Murdstones. Not only does she completely ignore Miss Murdstone, thus driving her crazy, but she also gives Mr. Murdstone a good dressing-down, and she really hits a sore point here:

”’It was clear enough, as I have told you, years before YOU ever saw her—and why, in the mysterious dispensations of Providence, you ever did see her, is more than humanity can comprehend—it was clear enough that the poor soft little thing would marry somebody, at some time or other; but I did hope it wouldn’t have been as bad as it has turned out. That was the time, Mr. Murdstone, when she gave birth to her boy here,’ said my aunt; ‘to the poor child you sometimes tormented her through afterwards, which is a disagreeable remembrance and makes the sight of him odious now. Aye, aye! you needn't wince!’ said my aunt. ‘I know it's true without that.’

He had stood by the door, all this while, observant of her with a smile upon his face, though his black eyebrows were heavily contracted. I remarked now, that, though the smile was on his face still, his colour had gone in a moment, and he seemed to breathe as if he had been running.”

During their conversation I could not help thinking that all in all, Murdstone seemed quite glad to wash his hands of his responsibility for David and that he was actually relieved to be able to get rid of him. If he had insisted on having David restored into his care, I do not doubt he would have succeeded by appealing to the law. In a way, however, he seems to have loved his young wife – because why else would he have winced at Aunt Betsey’s accusations? Is there a vestige of conscience even in someone like Mr. Murdstone?

At the end of the chapter, I have the impression of Dickens speaking himself through his narrator when he admits how difficult it was for him to raise the curtain that had covered his time in the factory:

”and that a curtain had for ever fallen on my life at Murdstone and Grinby's. No one has ever raised that curtain since. I have lifted it for a moment, even in this narrative, with a reluctant hand, and dropped it gladly. The remembrance of that life is fraught with so much pain to me, with so much mental suffering and want of hope, that I have never had the courage even to examine how long I was doomed to lead it. Whether it lasted for a year, or more, or less, I do not know. I only know that it was, and ceased to be; and that I have written, and there I leave it.”

It must have been very difficult – though probably also a relief – for Dickens to ascribe his own traumatic childhood experiences to one of his protagonists. Difficult, because he had to go through all his bad memories again, which must have been very painful; a relief, because writing it all down must probably have had a cathartic effect.

”’I suppose,’ said my aunt, eyeing me as narrowly as she had eyed the needle in threading it, ‘you think Mr. Dick a short name, eh?’

‘I thought it was rather a short name, yesterday,’ I confessed.

‘You are not to suppose that he hasn’t got a longer name, if he chose to use it,’ said my aunt, with a loftier air. ‘Babley—Mr. Richard Babley—that's the gentleman's true name.’

I was going to suggest, with a modest sense of my youth and the familiarity I had been already guilty of, that I had better give him the full benefit of that name, when my aunt went on to say:

‘But don’t you call him by it, whatever you do. He can’t bear his name. That’s a peculiarity of his. Though I don't know that it’s much of a peculiarity, either; for he has been ill-used enough, by some that bear it, to have a mortal antipathy for it, Heaven knows. Mr. Dick is his name here, and everywhere else, now—if he ever went anywhere else, which he don’t. So take care, child, you don’t call him anything BUT Mr. Dick.’”

And also this:

”’He has been CALLED mad,’ said my aunt. ‘I have a selfish pleasure in saying he has been called mad, or I should not have had the benefit of his society and advice for these last ten years and upwards—in fact, ever since your sister, Betsey Trotwood, disappointed me.’

‘So long as that?’ I said.

‘And nice people they were, who had the audacity to call him mad,’ pursued my aunt. ‘Mr. Dick is a sort of distant connexion of mine—it doesn't matter how; I needn't enter into that. If it hadn't been for me, his own brother would have shut him up for life. That’s all.’

I am afraid it was hypocritical in me, but seeing that my aunt felt strongly on the subject, I tried to look as if I felt strongly too.

‘A proud fool!’ said my aunt. ‘Because his brother was a little eccentric—though he is not half so eccentric as a good many people—he didn't like to have him visible about his house, and sent him away to some private asylum-place: though he had been left to his particular care by their deceased father, who thought him almost a natural. And a wise man he must have been to think so! Mad himself, no doubt.’

Again, as my aunt looked quite convinced, I endeavoured to look quite convinced also.

‘So I stepped in,’ said my aunt, ‘and made him an offer. I said, ‘Your brother's sane—a great deal more sane than you are, or ever will be, it is to be hoped. Let him have his little income, and come and live with me. I am not afraid of him, I am not proud, I am ready to take care of him, and shall not ill-treat him as some people (besides the asylum-folks) have done.’ After a good deal of squabbling,’ said my aunt, ‘I got him; and he has been here ever since. He is the most friendly and amenable creature in existence; and as for advice!—But nobody knows what that man’s mind is, except myself.’”

This not only tells us a lot about Mr. Dick but also about Aunt Betsey: namely that behind her rough façade there is a lot of kindness, and likewise that she has a peculiar way of looking at things. Not quite unlike Mr. Peggotty, Aunt Betsey has established a patchwork family of her own – interestingly, not that it had anything to do with the novel, this is also a recurring motif in some of Clint Eastwood’s films, like in The Outlaw Josey Wales –, and it is also interesting that she started taking care of Mr. Dick about the same time she was disappointed with regard to the outcome of Clara Copperfield’s pregnancy. I think that Aunt Betsey’s motive may lie in the bad experience she had with her own marriage, which made her distrustful of men in general – there are abundant examples of her skeptical view on marriage in her talk – but could not stifle her desire for company around her. Interestingly, Mr. Dick is a fool in whose wisdom Aunt Betsey hold implicit trust, whereas this did not go for her nephew, David’s father, whose naivety she likes to expound on.

I also stumbled across this little sentence here: “’Be as like your sister as you can, and speak out!’” Will David from now on have to live with being constantly compared to a sister who does not even exist? Will Aunt Betsey eventually reconcile herself to David`s being a boy? Together with Steerforth, there are already two people now who regret that David has no sister.

I really enjoyed the way Aunt Betsey had it out with the Murdstones. Not only does she completely ignore Miss Murdstone, thus driving her crazy, but she also gives Mr. Murdstone a good dressing-down, and she really hits a sore point here:

”’It was clear enough, as I have told you, years before YOU ever saw her—and why, in the mysterious dispensations of Providence, you ever did see her, is more than humanity can comprehend—it was clear enough that the poor soft little thing would marry somebody, at some time or other; but I did hope it wouldn’t have been as bad as it has turned out. That was the time, Mr. Murdstone, when she gave birth to her boy here,’ said my aunt; ‘to the poor child you sometimes tormented her through afterwards, which is a disagreeable remembrance and makes the sight of him odious now. Aye, aye! you needn't wince!’ said my aunt. ‘I know it's true without that.’

He had stood by the door, all this while, observant of her with a smile upon his face, though his black eyebrows were heavily contracted. I remarked now, that, though the smile was on his face still, his colour had gone in a moment, and he seemed to breathe as if he had been running.”

During their conversation I could not help thinking that all in all, Murdstone seemed quite glad to wash his hands of his responsibility for David and that he was actually relieved to be able to get rid of him. If he had insisted on having David restored into his care, I do not doubt he would have succeeded by appealing to the law. In a way, however, he seems to have loved his young wife – because why else would he have winced at Aunt Betsey’s accusations? Is there a vestige of conscience even in someone like Mr. Murdstone?

At the end of the chapter, I have the impression of Dickens speaking himself through his narrator when he admits how difficult it was for him to raise the curtain that had covered his time in the factory:

”and that a curtain had for ever fallen on my life at Murdstone and Grinby's. No one has ever raised that curtain since. I have lifted it for a moment, even in this narrative, with a reluctant hand, and dropped it gladly. The remembrance of that life is fraught with so much pain to me, with so much mental suffering and want of hope, that I have never had the courage even to examine how long I was doomed to lead it. Whether it lasted for a year, or more, or less, I do not know. I only know that it was, and ceased to be; and that I have written, and there I leave it.”

It must have been very difficult – though probably also a relief – for Dickens to ascribe his own traumatic childhood experiences to one of his protagonists. Difficult, because he had to go through all his bad memories again, which must have been very painful; a relief, because writing it all down must probably have had a cathartic effect.

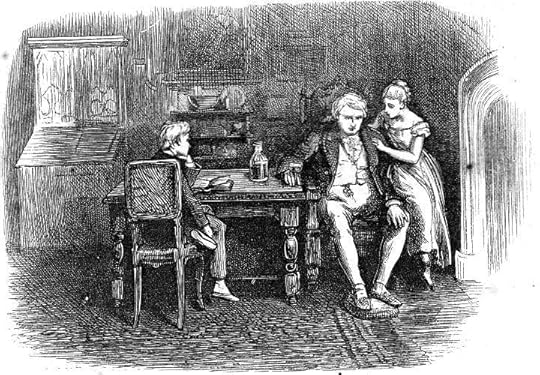

Chapter 15 prepares the scene for a new stage in David’s life and leads us on to Canterbury. Aunt Betsey, much to David’s relief, becomes aware of the fact that David is still in need of proper education and to provide it for him, she sends him to boarding school in Canterbury. Here we get to know Mr. Wickfield, Aunt Betsey’s family lawyer, and his daughter Agnes, the apple of his eye. There seems to be a mystery connected with Mr. Wickfield in some way because not only is he given to despondency but also to a rather excessive consumption of port wine in the evenings. I hope that this mystery will be unveiled in the course of the novel.

Agnes seems to be one of the typical female paragons – gentle, understanding, a good housewife, and rather colourless. One of the more promising characters is definitely Uriah Heep – what a name! –, who is described like this:

”The low arched door then opened, and the face came out. It was quite as cadaverous as it had looked in the window, though in the grain of it there was that tinge of red which is sometimes to be observed in the skins of red-haired people. It belonged to a red-haired person—a youth of fifteen, as I take it now, but looking much older—whose hair was cropped as close as the closest stubble; who had hardly any eyebrows, and no eyelashes, and eyes of a red-brown, so unsheltered and unshaded, that I remember wondering how he went to sleep. He was high-shouldered and bony; dressed in decent black, with a white wisp of a neckcloth; buttoned up to the throat; and had a long, lank, skeleton hand, which particularly attracted my attention, as he stood at the pony's head, rubbing his chin with it, and looking up at us in the chaise.”

As David shudders at the touch of Uriah Heep’s hand and feels that its damp coldness will not easily rub off, it is to be concluded that this creepy guy is going to mean trouble. Apart from that, Uriah’s habit of constantly watching David, with two eyes that seem like two red suns, may lead us to believe that in Uriah’s eyes, David is anything but a welcome guest at the Wickfields’ house, where he is going to lodge until Aunt Betsey has found an adequate place for her new ward in Canterbury. – Another trivium of Uriah’s creepiness occurs when he blows his breath into the horse’s nostrils and then keeps them shut with his hand as if to put a spell on the poor animal. Uriah Heep will definitely keep us busy!

One of my favourite scenes in this chapter, however, was the description of Mr. Dick and David letting their kite fly. Here, we have beautiful images likes this: ”I used to fancy, as I sat by him of an evening, on a green slope, and saw him watch the kite high in the quiet air, that it lifted his mind out of its confusion, and bore it (such was my boyish thought) into the skies.“ I must confess that the first few times I read the novel I couldn’t make much of Mr. Dick but this time, he really does intrigue me.

Agnes seems to be one of the typical female paragons – gentle, understanding, a good housewife, and rather colourless. One of the more promising characters is definitely Uriah Heep – what a name! –, who is described like this:

”The low arched door then opened, and the face came out. It was quite as cadaverous as it had looked in the window, though in the grain of it there was that tinge of red which is sometimes to be observed in the skins of red-haired people. It belonged to a red-haired person—a youth of fifteen, as I take it now, but looking much older—whose hair was cropped as close as the closest stubble; who had hardly any eyebrows, and no eyelashes, and eyes of a red-brown, so unsheltered and unshaded, that I remember wondering how he went to sleep. He was high-shouldered and bony; dressed in decent black, with a white wisp of a neckcloth; buttoned up to the throat; and had a long, lank, skeleton hand, which particularly attracted my attention, as he stood at the pony's head, rubbing his chin with it, and looking up at us in the chaise.”

As David shudders at the touch of Uriah Heep’s hand and feels that its damp coldness will not easily rub off, it is to be concluded that this creepy guy is going to mean trouble. Apart from that, Uriah’s habit of constantly watching David, with two eyes that seem like two red suns, may lead us to believe that in Uriah’s eyes, David is anything but a welcome guest at the Wickfields’ house, where he is going to lodge until Aunt Betsey has found an adequate place for her new ward in Canterbury. – Another trivium of Uriah’s creepiness occurs when he blows his breath into the horse’s nostrils and then keeps them shut with his hand as if to put a spell on the poor animal. Uriah Heep will definitely keep us busy!

One of my favourite scenes in this chapter, however, was the description of Mr. Dick and David letting their kite fly. Here, we have beautiful images likes this: ”I used to fancy, as I sat by him of an evening, on a green slope, and saw him watch the kite high in the quiet air, that it lifted his mind out of its confusion, and bore it (such was my boyish thought) into the skies.“ I must confess that the first few times I read the novel I couldn’t make much of Mr. Dick but this time, he really does intrigue me.

Chapter 13 -

Chapter 13 -Tristram wrote: "...whose treatment of his wife suggests another unhappily married couple. "

How were Charles and Catherine getting along at this point? It's easy to assume that the honeymoon was over. :-(

Tristram wrote: "Considering that he did not have any address and was not even sure whether Aunt Betsey lived in Dover or just in its vicinity, or was still alive in the first place, this was a very rare instance of good luck."

I always assume, conveniently, that 250 years ago, outside of London, at least, the population was significantly lower, and that people interacted more and actually knew their neighbors.

...is there actually any character without a whim in this novel?

Oh, dear - I hope not!

Chapter 14

Chapter 14Tristram wrote: " ...seeing that my aunt felt strongly on the subject, I tried to look as if I felt strongly too. ..."

David was mirroring Aunt Betsey long before the psychiatric community came up with a name for it. Nothing is new in human behavior.

Will David from now on have to live with being constantly compared to a sister who does not even exist?

I think it's a hoot the way Aunt Betsey talks about David's sister as though such a person actually exists. (Shades of Mrs. 'arris?) It's interesting that David doesn't really examine this or tell us his thoughts. Perhaps his birth story is so ingrained in his mind that he's not a bit surprised by it. However quirky and entertaining I've found it to be, though, you've sullied it by comparing it to Steerforth's comments about David having a sister. Harrumph. :-(

All in all, a very satisfying chapter. It's nice to end one a high note.

Addendum: Mr. Dick is one of those minor characters about whom I would have loved to have an entire novel. In fact, I think he goes to the top of that list.

Chapter 15

Chapter 15It belonged to a red-haired person—a youth of fifteen, as I take it now, but looking much older..."

Wait... what?? Uriah Heep is only a 15-year-old boy?! I'm gobsmacked. Over the years, I always assumed he was a man in his 20s, at least. This changes how I will interpret his character as we go forward.

Re: the kite - I'm reminded again of pop psychology, and people writing down those things that are preying on them and then burning the paper in a fire, or putting the paper in a balloon and then letting it fly away. Dickens was, once again, ahead of his time. I wonder, had he been born a century later, if Dickens would have gone into psychiatry. Or just contributed to the glut of books about getting along with people and finding happiness.

I simply loved these 3 chapters. My faith in DC has been fully rekindled!

I simply loved these 3 chapters. My faith in DC has been fully rekindled!David's journey from London to Dover had me literally biting my fingernails in anxiety. Such monsters along the way. I also thought of Oliver Twist, but the journey in DC is so much more interesting, what with all the juicy details Tristram mentioned.

I share your curiosity about the character of Mr. Dick. I couldn't help but notice this though: Aunty Betsey detests all men except one called Mr. Dick :) Apart from the lewd pun, Dick is also a truncated version of Dickens. Freud must have had a field day reading this novel!

Joking aside, I wonder if there ever was a character like Mr. Dick in earlier literature. The way he is described in these pages he could very well be an autistic person. And yet, instead of making a laughing stock of him Dickens depicts him with sympathy, kindness, respect. In fact isn't Mr. Dick so much more of a dignified human being (and has more common sense) than those despicable Murdstones?

Uriah Heep is also a fascinating character. That first impression we get of him: the stare, the clammy hands, the horse nostril trick. What a creep! Too bad he fits the red-haired devil stereotype. Otherwise he's the perfect villain.

This may seem like a silly question but how do you pronounce Uriah? Is it YOU-ria or yer-EYE-a (rhyming with pariah)?

Ulysse wrote: "I simply loved these 3 chapters. My faith in DC has been fully rekindled!

David's journey from London to Dover had me literally biting my fingernails in anxiety. Such monsters along the way. I als..."

Hi Ulysse

I’ve always pronounced Uriah to rhyme with “pariah.” I have no idea whether I’m correct or not but Uriah may well turn out to be somewhat a pariah.

David's journey from London to Dover had me literally biting my fingernails in anxiety. Such monsters along the way. I als..."

Hi Ulysse

I’ve always pronounced Uriah to rhyme with “pariah.” I have no idea whether I’m correct or not but Uriah may well turn out to be somewhat a pariah.

David’s trust in others leads him once again to be fooled, robbed and hoodwinked. Dickens doesn’t paint a rosy picture of the kindness to be found in others. Will much change as he matures?

David’s journey to find his aunt reminds me a bit of an odyssey, a child’s odyssey to find his way home. David is no Odysseus, and yet both David and Odysseus must face a series of challenges in order to reach their home destination. The concept of home is clearly strengthened in these chapters.

In this novel we have seen repeated references to Robinson Crusoe. He too found himself alone and homeless and had to use his wits to survive. One of his tasks was also to find a place to construct a home that would give him safety. I see David’s journey to find his aunt as his odyssey to reconnect with this family. It appears that this family will be unusual. Aunt Betsey still wonders about David’s phantom sister. Mr Dick is the voice of calm and reason and yet he appears to be simple-minded. That said, it is evident that David has found a new family and, through Aunt Betsey, is connected to his original family.

When the Murdstone’s appear they are treated like the invasive donkeys. They are dispatched quickly. They are, in no way family. The concept of family and the value of family has been initiated in these chapters.

David’s journey to find his aunt reminds me a bit of an odyssey, a child’s odyssey to find his way home. David is no Odysseus, and yet both David and Odysseus must face a series of challenges in order to reach their home destination. The concept of home is clearly strengthened in these chapters.

In this novel we have seen repeated references to Robinson Crusoe. He too found himself alone and homeless and had to use his wits to survive. One of his tasks was also to find a place to construct a home that would give him safety. I see David’s journey to find his aunt as his odyssey to reconnect with this family. It appears that this family will be unusual. Aunt Betsey still wonders about David’s phantom sister. Mr Dick is the voice of calm and reason and yet he appears to be simple-minded. That said, it is evident that David has found a new family and, through Aunt Betsey, is connected to his original family.

When the Murdstone’s appear they are treated like the invasive donkeys. They are dispatched quickly. They are, in no way family. The concept of family and the value of family has been initiated in these chapters.

Looking back in the novel Kim provided us with the Browne illustration of David returning to his home only to find his mother nursing a new child. In the illustration was a grandfather clock. In chapter 13 David notices that his aunt wears “a gentleman’s gold watch, if I might judge from its size and make, with an appropriate chain and seals.” Time and the passage of time is a trope in this novel. Aunt Betsey is the new keeper of time, the new recorder of the passage of time at this point in the novel.

I like how Aunt Betsey is on David's side now. What a pleasant surprise! Mr. Dick is an intriguing character. He's eccentric, yet calm and friendly. I wouldn't mind flying a kite with him.

I like how Aunt Betsey is on David's side now. What a pleasant surprise! Mr. Dick is an intriguing character. He's eccentric, yet calm and friendly. I wouldn't mind flying a kite with him.I'm enjoying the interesting scenes and side characters. I loved the, "Goroo, goroo!" guy. He's my new favorite. Not for cheating David, but for being a colorful, humorous character. "Oh, my eyes! Oh, my limbs! Oh, my lungs and liver! Goroo!" It was so funny, I was laughing the whole time. How did Dickens come up with this?

I'm listening to an audio book version of DC on Youtube. The narrator is great. He reads with feeling and makes different voices for the characters. He really brought the "goroo" guy to life.

I look forward to more scenes with Uriah Heep. What an intro! In the audio book, the narrator pronounces it like "pariah."

Oh how I loved these chapters! Go aunt Betsey, tell those Murdstones off! The Murdstones also made the wonderful, delightful mistake to arrive on donkeys, aunt Betsey's bane, thus making the greatest of bad first impressions on her.

Tristram wrote: "Peter’s point about food in this novel, or maybe even in Dickens in general, also made me aware of the fact that Aunt Betsey has the impression that David must have almost been starved to death and that she therefore spoon-feeds him, giving him little morsels of food only in order not to strain his stomach. What could that tell us about her?"

I do hope that it means that she is helping him on in life, and giving, and giving him kindness in such a way that he grows into it, and grows to trust adults again after his horrible experiences.

I too thought about something like autism with Mr. Dick btw. Imagine being sent off to an ant's hive like a Victorian asylum when you are already easily overstimulated. If that is the case, he was bound to thrive in a regular household like aunt Betsey's, where he is accepted and seen as the competent adult with eccentricities that he probably is, while he helps her to not forget the obvious things. Like 'whatever we do with the boy on the long term, let's bathe and feed him'. Probably David reeked so much Mr. Dick couldn't think for the stink with probably a more sensitive smell xD Also, everyone feels better with a full stomach, right?

Tristram wrote: "Peter’s point about food in this novel, or maybe even in Dickens in general, also made me aware of the fact that Aunt Betsey has the impression that David must have almost been starved to death and that she therefore spoon-feeds him, giving him little morsels of food only in order not to strain his stomach. What could that tell us about her?"

I do hope that it means that she is helping him on in life, and giving, and giving him kindness in such a way that he grows into it, and grows to trust adults again after his horrible experiences.

I too thought about something like autism with Mr. Dick btw. Imagine being sent off to an ant's hive like a Victorian asylum when you are already easily overstimulated. If that is the case, he was bound to thrive in a regular household like aunt Betsey's, where he is accepted and seen as the competent adult with eccentricities that he probably is, while he helps her to not forget the obvious things. Like 'whatever we do with the boy on the long term, let's bathe and feed him'. Probably David reeked so much Mr. Dick couldn't think for the stink with probably a more sensitive smell xD Also, everyone feels better with a full stomach, right?

Mary Lou wrote: "Chapter 13 -

Tristram wrote: "...whose treatment of his wife suggests another unhappily married couple. "

How were Charles and Catherine getting along at this point? It's easy to assume that the h..."

Ironically, however, in those unhappy couples we have got so far in DC it is mostly the woman who embodies values of benevolence, of care and of humanity, while the male part is doubtless tyrannical and unfair.

Tristram wrote: "...whose treatment of his wife suggests another unhappily married couple. "

How were Charles and Catherine getting along at this point? It's easy to assume that the h..."

Ironically, however, in those unhappy couples we have got so far in DC it is mostly the woman who embodies values of benevolence, of care and of humanity, while the male part is doubtless tyrannical and unfair.

Mary Lou wrote: "Chapter 15

It belonged to a red-haired person—a youth of fifteen, as I take it now, but looking much older..."

Wait... what?? Uriah Heep is only a 15-year-old boy?! I'm gobsmacked. Over the years,..."

What you say about the kite and popular psychology nowadays explains why DC was one of Freud's favourite novels.

It belonged to a red-haired person—a youth of fifteen, as I take it now, but looking much older..."

Wait... what?? Uriah Heep is only a 15-year-old boy?! I'm gobsmacked. Over the years,..."

What you say about the kite and popular psychology nowadays explains why DC was one of Freud's favourite novels.

Ulysse wrote: "I simply loved these 3 chapters. My faith in DC has been fully rekindled!

David's journey from London to Dover had me literally biting my fingernails in anxiety. Such monsters along the way. I als..."

Calloo-callay, Ulysse! I am glad to find that you are enjoying DC a bit better now as it is the first book you are reading with this group. I wholeheartedley concur to what you are saying about Mr. Dick - there is a lot of sympathy and understanding in the way our narrator describes this rather unusual character that struck me as too quirky and too odd the first time I read the novel.

As to Uriah Heep and the stereotype of the red-headed creep - he actually seems to have been based partly on Hans Christian Andersen, but I am going to provide some detail at a later point in our discussions, when Heep is going to play a bigger role.

David's journey from London to Dover had me literally biting my fingernails in anxiety. Such monsters along the way. I als..."

Calloo-callay, Ulysse! I am glad to find that you are enjoying DC a bit better now as it is the first book you are reading with this group. I wholeheartedley concur to what you are saying about Mr. Dick - there is a lot of sympathy and understanding in the way our narrator describes this rather unusual character that struck me as too quirky and too odd the first time I read the novel.

As to Uriah Heep and the stereotype of the red-headed creep - he actually seems to have been based partly on Hans Christian Andersen, but I am going to provide some detail at a later point in our discussions, when Heep is going to play a bigger role.

Alissa wrote: "I loved the, "Goroo, goroo!" guy. He's my new favorite. Not for cheating David, but for being a colorful, humorous character. "Oh, my eyes! Oh, my limbs! Oh, my lungs and liver! Goroo!" It was so funny, I was laughing the whole time. How did Dickens come up with this?"

I am almost sure that Dickens must have drawn that guy from real life. On his numerous rambles across London, he might well have observed a person like that; I don't think you can come up with something like that just from your imagination :-)

I am almost sure that Dickens must have drawn that guy from real life. On his numerous rambles across London, he might well have observed a person like that; I don't think you can come up with something like that just from your imagination :-)

I really enjoyed this section and I'm so happy to see something good happening for David. I certainly hope we are finished with the Murdstones, but I can't remember. I was also surprised by Uriah Heep's age, I thought that he was much older, as well.

I really enjoyed this section and I'm so happy to see something good happening for David. I certainly hope we are finished with the Murdstones, but I can't remember. I was also surprised by Uriah Heep's age, I thought that he was much older, as well. I am anxious to see the new DC movie but not sure I am ready to sit in a movie theatre. I see from the trailer one thing I don't really care for, they have David much older when he hears of his mother's death and arrives at his aunt's home. But, I do really like Dev Patel so that will make up for this, perhaps.

Thanks for the pronunciation tip everybody!

Thanks for the pronunciation tip everybody! Tristram, I had my moment my doubt re Mr. Dickens but am back to complete admiration now. It does help to read all these great comments from all of you :)

I've been waiting impatiently for the mailman to deliver the latest instalment of David's adventures. Two more days!

Ulysse,

I, too, find it hard not to read too much in advance, although as a mod I must read a little ahead of schedule. However, I always look at the illustrations of the next instalment to keep me wondering what might happen next.

I, too, find it hard not to read too much in advance, although as a mod I must read a little ahead of schedule. However, I always look at the illustrations of the next instalment to keep me wondering what might happen next.

Tristram wrote: "Ironically, however, in those unhappy couples we have got so far in DC it is mostly the woman who embodies values of benevolence, of care and of humanity, while the male part is doubtless tyrannical and unfair. ..."

Tristram wrote: "Ironically, however, in those unhappy couples we have got so far in DC it is mostly the woman who embodies values of benevolence, of care and of humanity, while the male part is doubtless tyrannical and unfair. ..."Excellent observation. Perhaps Dickens was more self-aware than I've given him credit for being. ;-)

As to Uriah's clammy hands... I happen to know someone who suffers from hyperhidrosis, and he is the best of men! It's a source of frustration and embarrassment when he must shake hands with people. Those who are aware might notice the quick wipe of his hands against his slacks when a handshake can't be avoided. People with hyperhidrosis must have mixed feelings about Coronavirus, which may just put an end to the handshake once and for all. At any rate, Uriah Heep may well turn out to be a villain but I, for one, won't jump to that conclusion based on his sweaty palms. :-)

Tristram wrote: "Alissa wrote: "I loved the, "Goroo, goroo!" guy. He's my new favorite. Not for cheating David, but for being a colorful, humorous character. "Oh, my eyes! Oh, my limbs! Oh, my lungs and liver! Goro..."

Tristram wrote: "Alissa wrote: "I loved the, "Goroo, goroo!" guy. He's my new favorite. Not for cheating David, but for being a colorful, humorous character. "Oh, my eyes! Oh, my limbs! Oh, my lungs and liver! Goro..."That guy was great. And Aunt Betsey is a breath of fresh air. Strangely enough I am taking my son to a(n outdoor socially-distanced) summer camp this week and there is a donkey wandering around the grounds all the time, and he's delightful. I don't understand what her problem is. :)

I also enjoyed her repeated references to David's sister, which were sort of a relief after reading Dombey and Son, (view spoiler). And although wishing so hard he was a girl is deeply unfair to David, I loved seeing Aunt B come around to the situation by re-naming him Trotwood and then Trot. And it's nice to see this boy being fed and educated and admired--at last.

Julie,

It is probably the conjunction of donkeys and boys, who lead the donkeys, that drives Aunt Betsey mad. Maybe, we are meant to read her continual sallies as a sign of her determination to keep her ground, to protect what is hers - after all, she thinks that patch of land in question belongs to her premises - and if we read it this way, this certainly bodes well for David because once she has acknowledged David, Aunt Betsey will be ready to fight for him.

It is probably the conjunction of donkeys and boys, who lead the donkeys, that drives Aunt Betsey mad. Maybe, we are meant to read her continual sallies as a sign of her determination to keep her ground, to protect what is hers - after all, she thinks that patch of land in question belongs to her premises - and if we read it this way, this certainly bodes well for David because once she has acknowledged David, Aunt Betsey will be ready to fight for him.

There's been a subtle shift in Aunt Betsey's attitude. She no longer just laments that David is not a girl. In creating a fictional sister, she's accepted David as his own person, albeit male. At least that's my take.

There's been a subtle shift in Aunt Betsey's attitude. She no longer just laments that David is not a girl. In creating a fictional sister, she's accepted David as his own person, albeit male. At least that's my take.

Yes, Mrs. Trotwood and her donkeys, here we go and I wasn't expecting this:

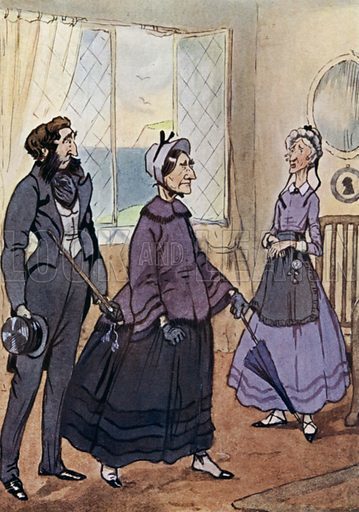

In the novel Miss Betsey has become so disappointed with men and with the whole institution of marriage that she breaks off relations with her beloved nephew, David Copperfield, Sr., when he marries a young nanny half his age. And she refuses to become the godmother of David Copperfield, Jr. because he is not the girl Miss Betsey was expecting. Of course, this heart-broken stubbornness shows itself in other, less dire ways. For example, she's immensely protective of a patch of lawn near her house. She watches it all day and half the night to make sure that no local donkeys are chowing down on her fine grass.

All of these examples of Miss Betsey's stubborn character – her refusal to speak to her nephew Mr. Copperfield after he marries unwisely, her initial rejection of David, and her chasing off of the donkeys – show that she is the total opposite of his mother.

The character is based on Miss Mary Pearson Strong who lived at Broadstairs, Kent, and who died on 14 January 1855; she is buried in the St. Peter's-in-Thanet churchyard. Her sister Ann married Stephen Nuckell, who was a prominent bookseller in Broadstairs from around 1796 to 1822. Mary Pearson Strong's former home now hosts Broadstairs' Dickens House Museum in Broadstairs, Kent. Miss Pearson would chase the seaside donkey-boys from the piece of garden in front of her cottage (the garden is still there, and still belongs to the house, although it is across a busy road). This was one of his inspirations for Betsey Trotwood in David Copperfield, part of which he wrote in the resort. According to the reminiscences of Dickens's son Charley, Miss Strong was a kindly and charming old lady who fed him tea and cakes. He also remembered that she was firmly convinced of her right to stop the passage of donkeys in front of the cottage. ("Dickens House Museum, Broadstairs").

Also, there is a public house in Clerkenwell, Central London, called The Betsey Trotwood. It adopted the name in 1983, having previously been The Butcher's Arms.

The City of Trotwood, Ohio is named after the character.

In the novel Miss Betsey has become so disappointed with men and with the whole institution of marriage that she breaks off relations with her beloved nephew, David Copperfield, Sr., when he marries a young nanny half his age. And she refuses to become the godmother of David Copperfield, Jr. because he is not the girl Miss Betsey was expecting. Of course, this heart-broken stubbornness shows itself in other, less dire ways. For example, she's immensely protective of a patch of lawn near her house. She watches it all day and half the night to make sure that no local donkeys are chowing down on her fine grass.

All of these examples of Miss Betsey's stubborn character – her refusal to speak to her nephew Mr. Copperfield after he marries unwisely, her initial rejection of David, and her chasing off of the donkeys – show that she is the total opposite of his mother.

The character is based on Miss Mary Pearson Strong who lived at Broadstairs, Kent, and who died on 14 January 1855; she is buried in the St. Peter's-in-Thanet churchyard. Her sister Ann married Stephen Nuckell, who was a prominent bookseller in Broadstairs from around 1796 to 1822. Mary Pearson Strong's former home now hosts Broadstairs' Dickens House Museum in Broadstairs, Kent. Miss Pearson would chase the seaside donkey-boys from the piece of garden in front of her cottage (the garden is still there, and still belongs to the house, although it is across a busy road). This was one of his inspirations for Betsey Trotwood in David Copperfield, part of which he wrote in the resort. According to the reminiscences of Dickens's son Charley, Miss Strong was a kindly and charming old lady who fed him tea and cakes. He also remembered that she was firmly convinced of her right to stop the passage of donkeys in front of the cottage. ("Dickens House Museum, Broadstairs").

Also, there is a public house in Clerkenwell, Central London, called The Betsey Trotwood. It adopted the name in 1983, having previously been The Butcher's Arms.

The City of Trotwood, Ohio is named after the character.

I googled Trotwood, Ohio. Sadly, it doesn't live up to its name.

I googled Trotwood, Ohio. Sadly, it doesn't live up to its name. The Pearson Strong house, however, looks charming.

Looking at Aunt Betsey and her home I found this:

HATE EXPECTATIONS Graffiti writer who vandalised Charles Dickens museum branding the author ‘racist’ boasts ‘I have no regrets’ he has admitted to vandalising the Charles Dickens museum - and boasts he has "no regrets". Ex-councillor Ian Driver scrawled "Dickens Racist" on the outside of the museum and tried to black out the Dickens Road street sign in Broadstairs, Kent. The culprit, Ian Driver, is a former councillor. He wore a denim jacket and cream shorts as he targeted the building in the early hours of Saturday in response to what he claims is "institutionalised racism" in the town.

As well as defacing the Dickens Museum, he also targeted council offices, the office of the Broadstairs Folk Week, the box protecting the controversial Uncle Mack memorial plaque and two street signs in town and Ramsgate. It comes after scores of statues were vandalised or pulled down in the wake of Black Lives Matter protests against racism throughout the country. Winston Churchill's statue was defaced in central London and slave trader Edward Colston's memorial was tossed into the harbour in Bristol last month.

Mr Driver, who was a Green Party councillor for four years until 2015, said today: "I have no regrets about my actions. I will be making no apology. "I did the right thing and would do it again if needs be." He branded Broadstairs "racism on sea" in his blog post and revealed he expected to be contacted by police. Writing on his blog, the brazen former local politician for Thanet said: “Just in case you hadn't already guessed, I was responsible for the spate of graffiti in Broadstairs and Ramsgate.” He was inspired by Broadstairs Town Council’s decision to retain the Uncle Mack memorial and Thanet Council’s review of its "publicly funded racist properties and activities". The museum represents historic racism and therefore deserves to be tarnished, he alleged.

Mr Driver went on: “I selected the targets as they represent the deep-rooted institutional racism of Broadstairs Town and Thanet District councils. Broadstairs Dickens Week and Folk Week charities openly support, celebrate, and fund with public money, offensive blacked up Morris dancers, Uncle Mack’s blacked up Minstrel show memorial, and genocidal racists such as Charles Dickens and King Leopold of Belgium.” The vandal revealed that the council’s lack of interest in his "personal protest" has led him to graffiti.

Driver continued: “I have been campaigning against, what I believe to be, the institutional racism of the Broadstairs and Dickens and Folk week events and the Broadstairs and Thanet councils for several years but to no avail. “I have now been forced, by the inaction, of these organisations to take direct measures to expose the appalling racism of our local government and some of our major charities who are being funded by the councils. Although I live here and love the place, in my opinion Broadstairs richly deserves the epithet Racism-on-Sea. My actions are nothing to do with the Black Lives Matter movement, of which I am a supporter, and are purely part of my own individual protest for which I alone am responsible.”

The toppling of the statue of slave owner Edward Colston in Bristol inspired Driver - and he maintains that defacing memorials is a "legitimate" part of protest. “I fully support and encourage this form of political expression wherever and whenever it is necessary, especially in my hometown which, to its shame, is rapidly becoming known as Racism-On-Sea”, he added. A street sign with Dickens' name on was also painted over. Divers said he did not regret his actions - and he wouldn't be apologising for defacing the various buildings. While a beloved British author behind many classics, Dickens' writing has been criticised as antisemitic and racist, with racial slurs against Indians.

The Dickens House Museum in Broadstairs, Kent, was the inspiration for Betsey Trotwood’s home in David Copperfield, and Dickens is known to have visited regularly. Shocked locals noticed "Dickens Racist, Dickens Racist" was left in black ink this weekend on the property’s front wall, while a road signed had been painted over.

Judith Carr said: “What madness! Aside from the fact that it is illegal to deface private property, Dickens spent his life pointing out the evils of social injustices of all kinds.” Phil Harradence said: “Please tell me the uneducated, knuckle dragging moron(s) responsible for this have been caught on CCTV? Have we now lost complete control of sense in this country, absolutely disgusting behaviour. What next, the blank cliffs of Dover???”

While a beloved British author behind many classics, Dickens' writing has been criticised as antisemitic and racist, with racial slurs against Indians documented. Dickens often holidayed in Broadstairs and wrote part of several of his books at Fort House - now Bleak House - up on the cliff tops. He also had a long association with Kent, beginning in 1817 when his father was posted to the naval dockyard in Chatham. He described the countryside between Rochester and Maidstone as some of the most beautiful in all England. And in 1856 he bought Gads Hill Place at Higham, in between Rochester and Gravesend, which is now Gad’s Hill School.

In a 1857 letter reacting to an uprising in India, he wrote he would like to "exterminate the Race from the face of the earth". And while he was known to be a champion of the poor, he often defended colonialism. Commenting on the graffiti, Poppy Elizabeth, said: “Not justifying it, I dislike graffiti. I'm just pointing out there is a level of truth. A lot of historical figures actually had views of ‘primitive’ cultures. I'm not saying he was a full blown kkk racist, but instead of jumping on this as mindless, do a bit of research and consider why this was put there.”

The property, named ‘Dickens House’ before the end of the 19th century, was bought by the Tattam family in 1919. In 1973 it was gifted to the town by Dora Tattam and opened as a museum according to the terms of her will. The character Betsey Trotwood is based on Miss Mary Pearson Strong who lived in the cottage that is now the museum. According to Charles Dickens’ son Charley, he and his father regularly had tea and cakes in the parlour with Miss Pearson Strong.

He said he chose the targets which represented 'deep-rooted institutional racism' - including the Town Hall Credit. The vandal revealed that the council’s lack of interest in his ‘personal protest’ has led him to this.

HATE EXPECTATIONS Graffiti writer who vandalised Charles Dickens museum branding the author ‘racist’ boasts ‘I have no regrets’ he has admitted to vandalising the Charles Dickens museum - and boasts he has "no regrets". Ex-councillor Ian Driver scrawled "Dickens Racist" on the outside of the museum and tried to black out the Dickens Road street sign in Broadstairs, Kent. The culprit, Ian Driver, is a former councillor. He wore a denim jacket and cream shorts as he targeted the building in the early hours of Saturday in response to what he claims is "institutionalised racism" in the town.

As well as defacing the Dickens Museum, he also targeted council offices, the office of the Broadstairs Folk Week, the box protecting the controversial Uncle Mack memorial plaque and two street signs in town and Ramsgate. It comes after scores of statues were vandalised or pulled down in the wake of Black Lives Matter protests against racism throughout the country. Winston Churchill's statue was defaced in central London and slave trader Edward Colston's memorial was tossed into the harbour in Bristol last month.

Mr Driver, who was a Green Party councillor for four years until 2015, said today: "I have no regrets about my actions. I will be making no apology. "I did the right thing and would do it again if needs be." He branded Broadstairs "racism on sea" in his blog post and revealed he expected to be contacted by police. Writing on his blog, the brazen former local politician for Thanet said: “Just in case you hadn't already guessed, I was responsible for the spate of graffiti in Broadstairs and Ramsgate.” He was inspired by Broadstairs Town Council’s decision to retain the Uncle Mack memorial and Thanet Council’s review of its "publicly funded racist properties and activities". The museum represents historic racism and therefore deserves to be tarnished, he alleged.

Mr Driver went on: “I selected the targets as they represent the deep-rooted institutional racism of Broadstairs Town and Thanet District councils. Broadstairs Dickens Week and Folk Week charities openly support, celebrate, and fund with public money, offensive blacked up Morris dancers, Uncle Mack’s blacked up Minstrel show memorial, and genocidal racists such as Charles Dickens and King Leopold of Belgium.” The vandal revealed that the council’s lack of interest in his "personal protest" has led him to graffiti.

Driver continued: “I have been campaigning against, what I believe to be, the institutional racism of the Broadstairs and Dickens and Folk week events and the Broadstairs and Thanet councils for several years but to no avail. “I have now been forced, by the inaction, of these organisations to take direct measures to expose the appalling racism of our local government and some of our major charities who are being funded by the councils. Although I live here and love the place, in my opinion Broadstairs richly deserves the epithet Racism-on-Sea. My actions are nothing to do with the Black Lives Matter movement, of which I am a supporter, and are purely part of my own individual protest for which I alone am responsible.”

The toppling of the statue of slave owner Edward Colston in Bristol inspired Driver - and he maintains that defacing memorials is a "legitimate" part of protest. “I fully support and encourage this form of political expression wherever and whenever it is necessary, especially in my hometown which, to its shame, is rapidly becoming known as Racism-On-Sea”, he added. A street sign with Dickens' name on was also painted over. Divers said he did not regret his actions - and he wouldn't be apologising for defacing the various buildings. While a beloved British author behind many classics, Dickens' writing has been criticised as antisemitic and racist, with racial slurs against Indians.

The Dickens House Museum in Broadstairs, Kent, was the inspiration for Betsey Trotwood’s home in David Copperfield, and Dickens is known to have visited regularly. Shocked locals noticed "Dickens Racist, Dickens Racist" was left in black ink this weekend on the property’s front wall, while a road signed had been painted over.

Judith Carr said: “What madness! Aside from the fact that it is illegal to deface private property, Dickens spent his life pointing out the evils of social injustices of all kinds.” Phil Harradence said: “Please tell me the uneducated, knuckle dragging moron(s) responsible for this have been caught on CCTV? Have we now lost complete control of sense in this country, absolutely disgusting behaviour. What next, the blank cliffs of Dover???”

While a beloved British author behind many classics, Dickens' writing has been criticised as antisemitic and racist, with racial slurs against Indians documented. Dickens often holidayed in Broadstairs and wrote part of several of his books at Fort House - now Bleak House - up on the cliff tops. He also had a long association with Kent, beginning in 1817 when his father was posted to the naval dockyard in Chatham. He described the countryside between Rochester and Maidstone as some of the most beautiful in all England. And in 1856 he bought Gads Hill Place at Higham, in between Rochester and Gravesend, which is now Gad’s Hill School.

In a 1857 letter reacting to an uprising in India, he wrote he would like to "exterminate the Race from the face of the earth". And while he was known to be a champion of the poor, he often defended colonialism. Commenting on the graffiti, Poppy Elizabeth, said: “Not justifying it, I dislike graffiti. I'm just pointing out there is a level of truth. A lot of historical figures actually had views of ‘primitive’ cultures. I'm not saying he was a full blown kkk racist, but instead of jumping on this as mindless, do a bit of research and consider why this was put there.”

The property, named ‘Dickens House’ before the end of the 19th century, was bought by the Tattam family in 1919. In 1973 it was gifted to the town by Dora Tattam and opened as a museum according to the terms of her will. The character Betsey Trotwood is based on Miss Mary Pearson Strong who lived in the cottage that is now the museum. According to Charles Dickens’ son Charley, he and his father regularly had tea and cakes in the parlour with Miss Pearson Strong.

He said he chose the targets which represented 'deep-rooted institutional racism' - including the Town Hall Credit. The vandal revealed that the council’s lack of interest in his ‘personal protest’ has led him to this.

I can't get an image of the graffiti to copy for a reason I don't understand, but you can google it if you want to see it. It says "Dickens racist" all over it.

Tristram wrote: "Agnes seems to be one of the typical female paragons – gentle, understanding, a good housewife, and rather colourless."

Grump.

Grump.

"Oh, my lungs and liver, will you go for threepence?"

Chapter 13

Fred Barnard

1872 Household Edition

Text Illustrated:

‘Oh, my liver!’ cried the old man, throwing the jacket on a shelf. ‘Get out of the shop! Oh, my lungs, get out of the shop! Oh, my eyes and limbs—goroo!—don’t ask for money; make it an exchange.’ I never was so frightened in my life, before or since; but I told him humbly that I wanted money, and that nothing else was of any use to me, but that I would wait for it, as he desired, outside, and had no wish to hurry him. So I went outside, and sat down in the shade in a corner. And I sat there so many hours, that the shade became sunlight, and the sunlight became shade again, and still I sat there waiting for the money.

There never was such another drunken madman in that line of business, I hope. That he was well known in the neighbourhood, and enjoyed the reputation of having sold himself to the devil, I soon understood from the visits he received from the boys, who continually came skirmishing about the shop, shouting that legend, and calling to him to bring out his gold. ‘You ain’t poor, you know, Charley, as you pretend. Bring out your gold. Bring out some of the gold you sold yourself to the devil for. Come! It’s in the lining of the mattress, Charley. Rip it open and let’s have some!’ This, and many offers to lend him a knife for the purpose, exasperated him to such a degree, that the whole day was a succession of rushes on his part, and flights on the part of the boys. Sometimes in his rage he would take me for one of them, and come at me, mouthing as if he were going to tear me in pieces; then, remembering me, just in time, would dive into the shop, and lie upon his bed, as I thought from the sound of his voice, yelling in a frantic way, to his own windy tune, the ‘Death of Nelson’; with an Oh! before every line, and innumerable Goroos interspersed. As if this were not bad enough for me, the boys, connecting me with the establishment, on account of the patience and perseverance with which I sat outside, half-dressed, pelted me, and used me very ill all day.

He made many attempts to induce me to consent to an exchange; at one time coming out with a fishing-rod, at another with a fiddle, at another with a cocked hat, at another with a flute. But I resisted all these overtures, and sat there in desperation; each time asking him, with tears in my eyes, for my money or my jacket. At last he began to pay me in halfpence at a time; and was full two hours getting by easy stages to a shilling.

‘Oh, my eyes and limbs!’ he then cried, peeping hideously out of the shop, after a long pause, ‘will you go for twopence more?’

‘I can’t,’ I said; ‘I shall be starved.’

‘Oh, my lungs and liver, will you go for threepence?’

‘I would go for nothing, if I could,’ I said, ‘but I want the money badly.’

‘Oh, go-roo!’ (it is really impossible to express how he twisted this ejaculation out of himself, as he peeped round the door-post at me, showing nothing but his crafty old head); ‘will you go for fourpence?’

I was so faint and weary that I closed with this offer; and taking the money out of his claw, not without trembling, went away more hungry and thirsty than I had ever been, a little before sunset. But at an expense of threepence I soon refreshed myself completely; and, being in better spirits then, limped seven miles upon my road.

David makes a bargain

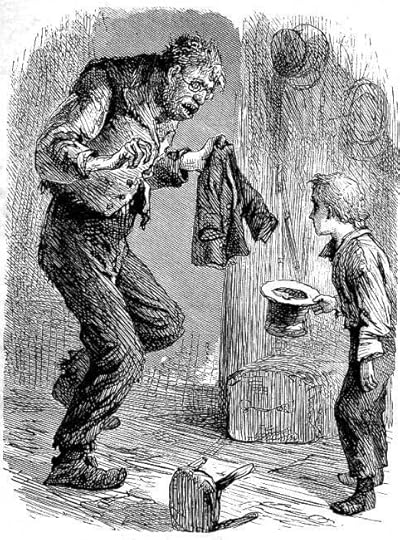

Chapter 13

Sol Eytinge, Jr.

1867 Diamond Edition

Commentary:

This sixth illustration is different from the previous five in that, instead of studying two or three characters in characteristic poses, it attempts to realize a very specific moment in the narrative. It is also the only illustration in Eytinge's series that depicts David, a middle class child reduced to the status of beggar and vagrant by the callous disregard of his stepfather. Determined to escape the squalor of London and the servitude of the wine-bottling warehouse — the equivalent of the blacking factory from the author's own childhood — in Chapter 13 David resolves to take the high road to Dover and seek out his Aunt Betsey Trotwood. At ten in the evening on the Kent Road, with the model of Micawber's practice in mind David decides to pawn his "weskit" at the second-hand clothing shop of Mr. Dolloby. The following day he attempts a similar transaction at an even more dismal and filthy shop in Rochester:

Into this shop, which was low and small, and which was darkened rather than lighted by a little window, over-hung with clothes, and was descended into by some steps, I went with a palpitating heart; which was not relieved when an ugly old man, with the lower part of his face all covered with a stubbly gray beard, rushed out of a dirty den behind it, and seized me by the hair of my head. He was a dreadful old man to look at, in a filthy flannel waistcoat, and smelling terribly of run.

Since the ogre, representative of all the repressive adult figures of David's childhood, is holding the boy's jacket, we may assume that this is the moment realized:

With that he took his trembling hands, which were like the claws of a great bird, out of my hair, and put on a pair of spectacles, not at all ornamental to his inflamed eyes.

"O, how much for the jacket?" cried the old man, after examining it. "O — goroo! — how much for the jacket?"

Eytinge has captured well the claw-like hands, the gigantic, bearded head, the ragged flannel waistcoat, all seeming so large when compared to the tiny jacket that he holds in his upstage (left) hand as he prances up and down, like some trained ape as the supplicating boy holds out a hat, as if soliciting change from a passerby.

When an ugly old man

Ch. 13

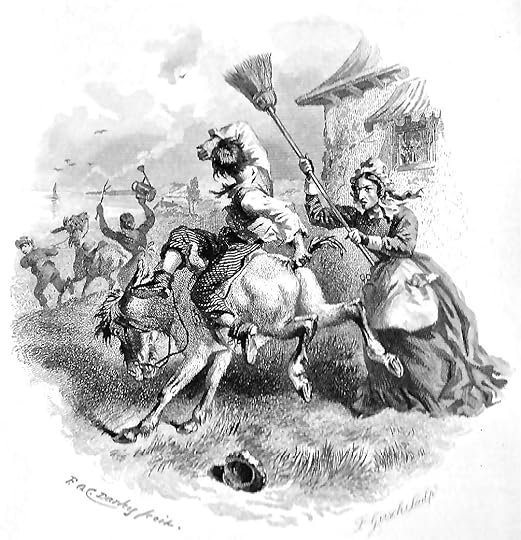

Felix O. C. Darley

1867

Text Illustrated:

An ugly old man, with the lower part of his face all covered with a stubbly grey beard, rushed out of a dirty den behind it, and seized me by the hair of my head. He was a dreadful old man to look at, in a filthy flannel waistcoat, and smelling terribly of rum. His bedstead, covered with a tumbled and ragged piece of patchwork, was in the den he had come from, where another little window showed a prospect of more stinging-nettles, and a lame donkey.

"Oh, what do you want?" grinned this old man, in a fierce, monotonous whine. "Oh, my eyes and limbs, what do you want? Oh, my lungs and liver, what do you want? Oh, goroo, goroo!"

Commentary:

Determined to escape the squalor of London and the servitude of the wine-bottling warehouse — the equivalent of the blacking factory from the author's own childhood — in Chapter 13 David resolves to take the high road to Dover and take the gamble of throwing himself upon the mercy of his aunt, Betsey Trotwood, in Dover — a considerable distance for a pedestrian with no resources, let alone a child. At ten in the evening on the Kent Road, with the model of Micawber's practice in mind David decides to pawn his "weskit" at the second-hand clothing shop of Mr. Dolloby. The following day he attempts a similar transaction at an even more dismal and filthy shop in Rochester, the scene illustrated by Darley in his initial frontispiece for the novel in the four-volume set.

Although the monthly illustration by Hablot Knight Browne in the May 1849-November 1850 part-publication offered Darley, working throughout the 1860s in America, plenty of models for young David, the "Goroo Man," the used clothing dealer in Part 5 (September 1849), does not appear in the pair of monthly illustrations. Although Sol Eytinge, Jr. in The Diamond Edition (1867) and Fred Barnard in Household Edition have created images relevant to a discussion of the early visual history of the novel, Darley would have had access to neither narrative-pictorial sequence, both of which include this terrifying incident. Consequently, we may regard this frontispiece as a Darley original.

Darley, lacking precedent for an illustration of this incident, should have consulted the original serial illustrations for images of David as a child, particularly the September 1849 steel-engraving I make myself known to my Aunt (May 1847) — which clearly shows David's ragged condition, although (as a scion of the bourgeoisie) he has retained his hat, battered though it may be. However, David in the Darley illustration is simply too well dressed, although perhaps it was his intention to contrast the well-dressed child with the ill-kempt, ragged second-hand clothing vendor.

In the same year that Darley executed this frontispiece, his colleague at Ticknor & Fields in Boston, Sol Eytinge, Jr., was working on a short series of illustrations for The Personal History of David Copperfield as part of the mammoth task of illustrating single-handedly the entire Diamond Edition. The small-scale wood-engravings are hastily executed and tend to focus on a pair of associated characters, but some of them are effective in capturing Rodinesque poses and textual moments. David's Bargain is the only illustration in Eytinge's series that depicts David, a middle class child reduced to the status of beggar and vagrant by the callous disregard of his stepfather. The ogre, representative of all the repressive adult figures of David's childhood, is already holding the boy's jacket, so that the threat he poses David is imminent. Eytinge has captured well the claw-like hands, the gigantic, bearded head, the ragged flannel waistcoat, all seeming so large when compared to the tiny jacket that he holds in his upstage (left) hand as he prances up and down, like some trained ape as the supplicating boy holds out a hat, as if soliciting change from a passerby; the realistic figure in the Darley illustration is far less menacing, so that the illustrator must communicate the underlying terror of the recollected moment through David's posture and expression.

Whereas Barnard in the 1872 Household Edition wood-engraving "Oh, my lungs and liver, will you go for threepence?" effectively depicts the "Garoo-Man" as a demented, old wretch with a strangling beard, he does not capture the moment when the vendor grabs David, who in Barnard's illustration is sitting calmly on the doorstep to the shop, separated from the menacing figure by a dining-table cluttered with bric-a-brac; the kite and twine under the table are visual foreshadowing of David's meeting Mr. Dick. However, Darley shows nothing but items of used clothing in the shop, which is much tidier than Barnard's, and therefore less true to the letter-press.

The whole day was a succession of rushes on his part, and flights on the part of the boys

Chapter 13

F.M.B. Blaikie

Illustration for David Copperfield retold for children by Alice F Jackson 1920

Text Illustrated:

There never was such another drunken madman in that line of business, I hope. That he was well known in the neighbourhood, and enjoyed the reputation of having sold himself to the devil, I soon understood from the visits he received from the boys, who continually came skirmishing about the shop, shouting that legend, and calling to him to bring out his gold. ‘You ain’t poor, you know, Charley, as you pretend. Bring out your gold. Bring out some of the gold you sold yourself to the devil for. Come! It’s in the lining of the mattress, Charley. Rip it open and let’s have some!’ This, and many offers to lend him a knife for the purpose, exasperated him to such a degree, that the whole day was a succession of rushes on his part, and flights on the part of the boys. Sometimes in his rage he would take me for one of them, and come at me, mouthing as if he were going to tear me in pieces; then, remembering me, just in time, would dive into the shop, and lie upon his bed, as I thought from the sound of his voice, yelling in a frantic way, to his own windy tune, the ‘Death of Nelson’; with an Oh! before every line, and innumerable Goroos interspersed. As if this were not bad enough for me, the boys, connecting me with the establishment, on account of the patience and perseverance with which I sat outside, half-dressed, pelted me, and used me very ill all day.

I find it interesting that the only one of our illustrations who doesn't take a turn in the selling his jacket illustrations is Phiz. And the shop keeper in Sol Eytinge's illustration looks like an ape.

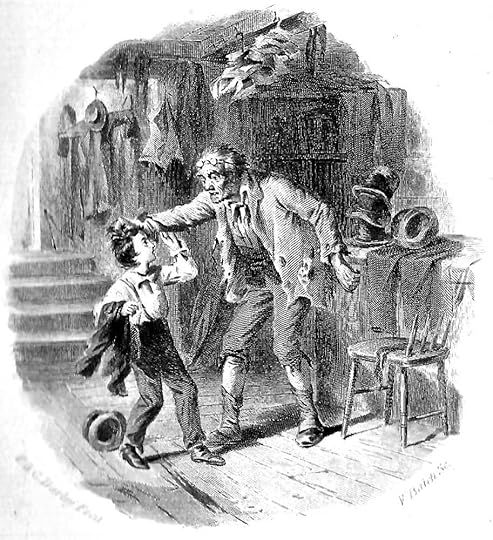

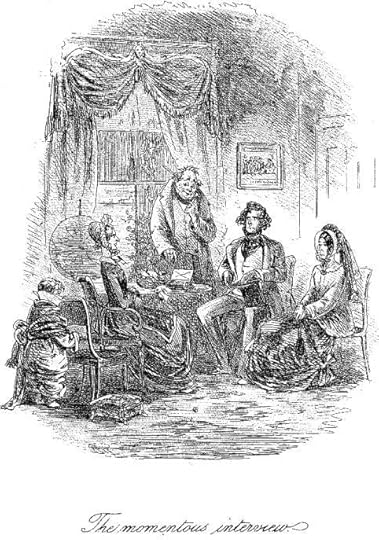

I make myself known to my Aunt

Chapter 13

Phiz

Two working drawings:

Commentary:

The first illustration for the fifth monthly number, containing chapters 13, 14, and 15, marks the transition of the narrator's identity, from "David" to "Trotwood," and from a neglected orphan and vagabond to a child adopted by an unconventional family, his aunt, the affluent but eccentric Betsey Trotwood, and her companion, the benign but demented Mr. Dick. Volume readers have already been introduced to Miss Betsey through the novel's frontispiece, but the serial readers had encountered her only briefly in the opening chapter. The fairy-godmother of this modern rags-to- riches fairy-tale, Aunt Betsey will become the surrogate mother for whom David has been searching ever since his mother's death. The scene occurs at her cottage not far from Dover, to which David has walked all the way from London, the crotchety old maid being the boy's last best hope of salvation:

One of the best known of Browne's illustrations is the first of the pair concluding David's childhood tribulations. Browne originally offered a drawing for "I make myself known to my Aunt" (ch. 13) that showed Betsey Trotwood sitting "flat down in the garden-path" with astonishment when David announces who he is. The etching (for which I have not located the final, working drawing, though the other two, as well as a preliminary first version, are in Elkins) combines the figure of Betsey in the second version with the more appealing figure of David as he is in the first. It is a good solution, since Betsey's essential dignity is retained without scanting her personal eccentricity. When asked what is Betsey's reaction to David, I would wager that most readers of the illustrated edition would reply in terms of Phiz's etching rather than the text. [Steig 119]

And, of course, most readers would be wrong, since the sketch which Dickens rejected, in which Browne depicts Aunt Betsey sitting upright on the ground, and therefore no higher than David. The original sketches of "I make myself known to my Aunt," each approximately six-inches square, are now in the Elkins Collection of the Rare Book Department of The Free Library of Philadelphia, and have been reproduced by both Steig and Cohen. In these pencil sketches, as in the final version, Aunt Betsey is in her gardening costume, and has hollyhocks behind her, climbing the wall, so that the wall and plant are analagous to the woman and the boy, who with her support will grow emotionally as well as physically. Allowed to go to seed through the neglect of the Murdstones, David finds himself in a more nurturing environment, as is evident from the abundant growth of the plants in Aunt Betsey's garden. Discounting the presence of the young donkey-boys and their obstreperous charges (who will shortly appear as interlopers in the well-tended garden in the text), upper centre, the moment dramatized in the illustration does not quite correspond to the momentous meeting of David and his aunt as described by Dickens:

there came out of the house a lady with her handkerchief tied over her cap, and a pair of gardening gloves on her hands, wearing a gardening pocket like a toll-man's apron, and carrying a great knife. I knew her immediately to be Miss Betsey, fr she came stalking out of the house exactly as my poor mother had so often described her stalking up our garden at Blunderstone Rookery.

"Go away!" said Miss Betsey, shaking her head, and making a distant chop in the air with her knife. "Go along! No boys here."

I watched her, with my heart at my lips, as she marched to a corner of her garden, and stooped to dig up some little root there. Then, without a scrap of courage, but with a great deal of desperation, I went softly in and stood beside her, touching her with my finger.

"If you please, ma'am," I began.

She started and looked up.

"If you please, aunt."

"Eh?" exclaimed Miss Betsey, in a tone of amazement I have never heard approached.

"if you please, aunt, I am your nephew."

Since she is still standing, rather than bowled over with amazement, this is the point captured, even if the donkey-boy and mount shown approaching Miss Betsey's garden gate do not in fact arrive for some four pages.

(I'll look for the other illustration after I finished with the ones that made it into the book.)

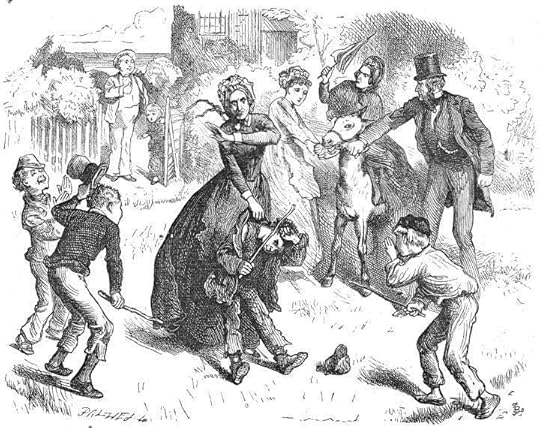

The Battle on the Green

Chapter 13

Fred Barnard

1872 Household Edition

Text Illustrated:

Janet had gone away to get the bath ready, when my aunt, to my great alarm, became in one moment rigid with indignation, and had hardly voice to cry out, ‘Janet! Donkeys!’

Upon which, Janet came running up the stairs as if the house were in flames, darted out on a little piece of green in front, and warned off two saddle-donkeys, lady-ridden, that had presumed to set hoof upon it; while my aunt, rushing out of the house, seized the bridle of a third animal laden with a bestriding child, turned him, led him forth from those sacred precincts, and boxed the ears of the unlucky urchin in attendance who had dared to profane that hallowed ground.

To this hour I don’t know whether my aunt had any lawful right of way over that patch of green; but she had settled it in her own mind that she had, and it was all the same to her. The one great outrage of her life, demanding to be constantly avenged, was the passage of a donkey over that immaculate spot. In whatever occupation she was engaged, however interesting to her the conversation in which she was taking part, a donkey turned the current of her ideas in a moment, and she was upon him straight. Jugs of water, and watering-pots, were kept in secret places ready to be discharged on the offending boys; sticks were laid in ambush behind the door; sallies were made at all hours; and incessant war prevailed. Perhaps this was an agreeable excitement to the donkey-boys; or perhaps the more sagacious of the donkeys, understanding how the case stood, delighted with constitutional obstinacy in coming that way. I only know that there were three alarms before the bath was ready; and that on the occasion of the last and most desperate of all, I saw my aunt engage, single-handed, with a sandy-headed lad of fifteen, and bump his sandy head against her own gate, before he seemed to comprehend what was the matter. These interruptions were of the more ridiculous to me, because she was giving me broth out of a table-spoon at the time (having firmly persuaded herself that I was actually starving, and must receive nourishment at first in very small quantities), and, while my mouth was yet open to receive the spoon, she would put it back into the basin, cry ‘Janet! Donkeys!’ and go out to the assault.

Janet! Donkeys!

Chapter 13

Felix O. C. Darley

1863

Text Illustrated:

My aunt, to my great alarm, became in one moment rigid with indignation, and had hardly voice to cry out, "Janet! Donkeys!"

Upon which, Janet came running up the stairs as if the house were in flames, darted out on a little piece of green in front, and warned off two saddle-donkeys, lady-ridden, that had presumed to set hoof upon it; while my aunt, rushing out of the house, seized the bridle of a third animal laden with a bestriding child, turned him, led him forth from those sacred precincts, and boxed the ears of the unlucky urchin in attendance who had dared to profane that hallowed ground. . . . [T]here were three alarms before the bath was ready; and that on the occasion of the last and most desperate of all, I saw my aunt engage, single-handed, with a sandy-headed lad of fifteen, and bump his sandy head against her own gate, before he seemed to comprehend what was the matter. [Chapter 13]

Commentary: