The Old Curiosity Club discussion

This topic is about

David Copperfield

David Copperfield

>

DC, Chp. 38-40

Chapter 39 is titled "Wickfield and Heep" and it is with them we spend most of our time. At the beginning of the chapter Aunt Betsey asks David to go to Dover, mostly because she is worried about his depression, but she tells him it is "to see that all was working well at the cottage, which was let; and to conclude an agreement, with the same tenant, for a longer term of occupation." After checking on the cottage which he finds in satisfactory shape he is able to tell his aunt that the new tenant is carrying on the war against the donkeys. I wonder what it is these evil donkeys manage to do when they are near the cottage that is so terrible to be driven away by everyone? Of course I wouldn't want to clean donkey poop out of my front yard, maybe that's it. He then goes to visit Mr. Wickfield and Agnes. When he arrives at the house he finds Mr. Micawber sitting in Uriah's old seat "plying his pen with great assiduity" and wearing a legal-looking black suit. He tells David he and his family are now living in Uriah Heep's old house and Uriah and his mother now live with the Wickfield's. David seems to think that Mr. Micawber has changed since he began working for Uriah, that it is an uneasy change about him.

David then goes to the drawing room where he finds Agnes alone and sitting by the fire. He talks to Agnes about his troubles and comments often of how much he misses her advice on matters.

'Whenever I have not had you, Agnes, to advise and approve in the beginning, I have seemed to go wild, and to get into all sorts of difficulty. When I have come to you, at last (as I have always done), I have come to peace and happiness. I come home, now, like a tired traveller, and find such a blessed sense of rest!'

David tells her that he finds it difficult to confide in Dora in the same way because though she is "the soul of purity and truth" she is also a timid little thing and so "easily disturbed and frightened." Agnes suggests to David that he write to Dora's aunts and seek permission to visit Dora. David agrees and spends the afternoon writing the letter. From this time on although David would like to spend more time alone with Agnes, Mrs. Heep joins them and doesn't leave them the rest of the day.

"At dinner she maintained her watch, with the same unwinking eyes. After dinner, her son took his turn; and when Mr. Wickfield, himself, and I were left alone together, leered at me, and writhed until I could hardly bear it. In the drawing-room, there was the mother knitting and watching again. All the time that Agnes sang and played, the mother sat at the piano. Once she asked for a particular ballad, which she said her Ury (who was yawning in a great chair) doted on; and at intervals she looked round at him, and reported to Agnes that he was in raptures with the music. But she hardly ever spoke—I question if she ever did—without making some mention of him. It was evident to me that this was the duty assigned to her."

The next day during a walk that Uriah has joined David on even though it was obvious David wanted to be anywhere but with Uriah, David tells Uriah that he is engaged to someone other than Agnes, and Uriah in his joy admits that he asked Mrs. Heep to follow David and Agnes around. He once again professes his love for Agnes and his intention to marry her. Then he tells David that his father taught him to be humble and ingratiating in order to succeed in the world until I am once again sick of seeing the word 'umble. His father taught him how to make everyone in the world hate him, if that's what being humble is like.

"They taught us all a deal of umbleness—not much else that I know of, from morning to night. We was to be umble to this person, and umble to that; and to pull off our caps here, and to make bows there; and always to know our place, and abase ourselves before our betters. And we had such a lot of betters! Father got the monitor-medal by being umble. So did I. Father got made a sexton by being umble. He had the character, among the gentlefolks, of being such a well-behaved man, that they were determined to bring him in. "Be umble, Uriah," says father to me, "and you'll get on. It was what was always being dinned into you and me at school; it's what goes down best. Be umble," says father, "and you'll do!" And really it ain't done bad!'"

Uriah observes that, although he is humble, he does have some power. That evening after dinner Uriah tells David and Mr. Wickfield of his intention to be Agnes' husband and when Mr. Wickfield hears that he jumps to his feet. I thought he was going to attack Uriah then and there old or not. I also thought it would probably kill him, I wonder what will happen to Agnes when her father dies. I wonder the same thing about Dora being without her father now, neither one has a mother.

"I had my arms round Mr. Wickfield, imploring him by everything that I could think of, oftenest of all by his love for Agnes, to calm himself a little. He was mad for the moment; tearing out his hair, beating his head, trying to force me from him, and to force himself from me, not answering a word, not looking at or seeing anyone; blindly striving for he knew not what, his face all staring and distorted—a frightful spectacle."

Mr. Wickfield calls Uriah his torturer and says' before him I have step by step abandoned name and reputation, peace and quiet, house and home." I wonder what it is that has caused him to follow Uriah step by step into this dark place he now seems to be in. I wonder what it is this power Uriah has over him.

The next morning as David is leaving in the coach Uriah arrives admits that perhaps he has "plucked a pear before it was ripe." But then says, "It'll ripen yet! I can wait!” Lucky Agnes.

David then goes to the drawing room where he finds Agnes alone and sitting by the fire. He talks to Agnes about his troubles and comments often of how much he misses her advice on matters.

'Whenever I have not had you, Agnes, to advise and approve in the beginning, I have seemed to go wild, and to get into all sorts of difficulty. When I have come to you, at last (as I have always done), I have come to peace and happiness. I come home, now, like a tired traveller, and find such a blessed sense of rest!'

David tells her that he finds it difficult to confide in Dora in the same way because though she is "the soul of purity and truth" she is also a timid little thing and so "easily disturbed and frightened." Agnes suggests to David that he write to Dora's aunts and seek permission to visit Dora. David agrees and spends the afternoon writing the letter. From this time on although David would like to spend more time alone with Agnes, Mrs. Heep joins them and doesn't leave them the rest of the day.

"At dinner she maintained her watch, with the same unwinking eyes. After dinner, her son took his turn; and when Mr. Wickfield, himself, and I were left alone together, leered at me, and writhed until I could hardly bear it. In the drawing-room, there was the mother knitting and watching again. All the time that Agnes sang and played, the mother sat at the piano. Once she asked for a particular ballad, which she said her Ury (who was yawning in a great chair) doted on; and at intervals she looked round at him, and reported to Agnes that he was in raptures with the music. But she hardly ever spoke—I question if she ever did—without making some mention of him. It was evident to me that this was the duty assigned to her."

The next day during a walk that Uriah has joined David on even though it was obvious David wanted to be anywhere but with Uriah, David tells Uriah that he is engaged to someone other than Agnes, and Uriah in his joy admits that he asked Mrs. Heep to follow David and Agnes around. He once again professes his love for Agnes and his intention to marry her. Then he tells David that his father taught him to be humble and ingratiating in order to succeed in the world until I am once again sick of seeing the word 'umble. His father taught him how to make everyone in the world hate him, if that's what being humble is like.

"They taught us all a deal of umbleness—not much else that I know of, from morning to night. We was to be umble to this person, and umble to that; and to pull off our caps here, and to make bows there; and always to know our place, and abase ourselves before our betters. And we had such a lot of betters! Father got the monitor-medal by being umble. So did I. Father got made a sexton by being umble. He had the character, among the gentlefolks, of being such a well-behaved man, that they were determined to bring him in. "Be umble, Uriah," says father to me, "and you'll get on. It was what was always being dinned into you and me at school; it's what goes down best. Be umble," says father, "and you'll do!" And really it ain't done bad!'"

Uriah observes that, although he is humble, he does have some power. That evening after dinner Uriah tells David and Mr. Wickfield of his intention to be Agnes' husband and when Mr. Wickfield hears that he jumps to his feet. I thought he was going to attack Uriah then and there old or not. I also thought it would probably kill him, I wonder what will happen to Agnes when her father dies. I wonder the same thing about Dora being without her father now, neither one has a mother.

"I had my arms round Mr. Wickfield, imploring him by everything that I could think of, oftenest of all by his love for Agnes, to calm himself a little. He was mad for the moment; tearing out his hair, beating his head, trying to force me from him, and to force himself from me, not answering a word, not looking at or seeing anyone; blindly striving for he knew not what, his face all staring and distorted—a frightful spectacle."

Mr. Wickfield calls Uriah his torturer and says' before him I have step by step abandoned name and reputation, peace and quiet, house and home." I wonder what it is that has caused him to follow Uriah step by step into this dark place he now seems to be in. I wonder what it is this power Uriah has over him.

The next morning as David is leaving in the coach Uriah arrives admits that perhaps he has "plucked a pear before it was ripe." But then says, "It'll ripen yet! I can wait!” Lucky Agnes.

In Chapter 40, "The Wanderer" David tells us of how when he told his aunt of the domestic occurrences at the Wickfield house, his aunt walks back and forth for more than two hours thinking of the things he had said. This reminded me of how many people I see on cell phones just walk around while talking on them, why it reminded me of that I don't know, it just does. Family and friends that I have will walk back and forth through the house or up and down the driveway all the while talking on the phone. It makes me wonder how people ever managed to have a phone conversation when all the phones were still connected to the wall.

Anyway, David sends his letter to Dora's aunts and impatiently waits for an answer. Meanwhile, one night as he is walking home from Dr. Strong's house he sees a woman that looks familiar to him but he doesn't remember where he has seen her before. As he is thinking of this a man who is sitting on the steps of a church stands up and walks over to him and David realizes it is Mr. Peggoty. He then realizes the woman whom he passed was Martha Endell, the "fallen woman" whom Emily had once helped. David and Mr. Peggotty go to one of the public rooms of an inn which is empty and has a good fire burning. Of Mr. Peggotty's appearance David says this:

..." not only that his hair was long and ragged, but that his face was burnt dark by the sun. He was greyer, the lines in his face and forehead were deeper, and he had every appearance of having toiled and wandered through all varieties of weather; but he looked very strong, and like a man upheld by steadfastness of purpose, whom nothing could tire out."

Mr. Peggotty shows David the letters which were received from Emily while he was out looking for her on the continent. Mr. Peggotty has come close to finding her a few times, but has always missed her. In all Emily has sent three letters. In one she asks for understanding and forgiveness, and saying clearly that she will never return. The letters Emily sent contain money, obviously originating from Steerforth, but Mr. Peggotty vows that he will return every cent of the money if he has to go "ten thousand miles." The last note received bears the postmark of a town on the Upper Rhine, and Mr. Peggotty declares that he is going there now in search of her. Throughout Mr. Peggotty's story, David sees Martha Endell listening at the inn door. After awhile they part, and the grieving uncle "resumes his journey". His last words to David are:

'I'd go ten thousand mile,' he said, 'I'd go till I dropped dead, to lay that money down afore him. If I do that, and find my Em'ly, I'm content. If I doen't find her, maybe she'll come to hear, sometime, as her loving uncle only ended his search for her when he ended his life; and if I know her, even that will turn her home at last!'

I was confused at the end of the chapter because David says he saw the lonely figure of Martha "flit away before them". I thought when David saw her at the beginning of the chapter that she was with Mr. Peggotty, I thought he must have found her in his travels and brought her with him, but it seems to me now like he didn't know she was there. So was she following him? And if she is, why? It seems a little too much of a coincidence that Martha and Mr. Peggotty would end up at the same place at the same time doesn't it? Of course Miss Murdstone ending up with Dora, Mr. Murdstone being with her father, Mr. Micawber showing up from nowhere with Traddles living with him all seem a little too hard to believe too. And yet we believe it. Any time now a boy leading a donkey that used to be on Aunt Betsey's lawn should show up.

Anyway, David sends his letter to Dora's aunts and impatiently waits for an answer. Meanwhile, one night as he is walking home from Dr. Strong's house he sees a woman that looks familiar to him but he doesn't remember where he has seen her before. As he is thinking of this a man who is sitting on the steps of a church stands up and walks over to him and David realizes it is Mr. Peggoty. He then realizes the woman whom he passed was Martha Endell, the "fallen woman" whom Emily had once helped. David and Mr. Peggotty go to one of the public rooms of an inn which is empty and has a good fire burning. Of Mr. Peggotty's appearance David says this:

..." not only that his hair was long and ragged, but that his face was burnt dark by the sun. He was greyer, the lines in his face and forehead were deeper, and he had every appearance of having toiled and wandered through all varieties of weather; but he looked very strong, and like a man upheld by steadfastness of purpose, whom nothing could tire out."

Mr. Peggotty shows David the letters which were received from Emily while he was out looking for her on the continent. Mr. Peggotty has come close to finding her a few times, but has always missed her. In all Emily has sent three letters. In one she asks for understanding and forgiveness, and saying clearly that she will never return. The letters Emily sent contain money, obviously originating from Steerforth, but Mr. Peggotty vows that he will return every cent of the money if he has to go "ten thousand miles." The last note received bears the postmark of a town on the Upper Rhine, and Mr. Peggotty declares that he is going there now in search of her. Throughout Mr. Peggotty's story, David sees Martha Endell listening at the inn door. After awhile they part, and the grieving uncle "resumes his journey". His last words to David are:

'I'd go ten thousand mile,' he said, 'I'd go till I dropped dead, to lay that money down afore him. If I do that, and find my Em'ly, I'm content. If I doen't find her, maybe she'll come to hear, sometime, as her loving uncle only ended his search for her when he ended his life; and if I know her, even that will turn her home at last!'

I was confused at the end of the chapter because David says he saw the lonely figure of Martha "flit away before them". I thought when David saw her at the beginning of the chapter that she was with Mr. Peggotty, I thought he must have found her in his travels and brought her with him, but it seems to me now like he didn't know she was there. So was she following him? And if she is, why? It seems a little too much of a coincidence that Martha and Mr. Peggotty would end up at the same place at the same time doesn't it? Of course Miss Murdstone ending up with Dora, Mr. Murdstone being with her father, Mr. Micawber showing up from nowhere with Traddles living with him all seem a little too hard to believe too. And yet we believe it. Any time now a boy leading a donkey that used to be on Aunt Betsey's lawn should show up.

The next morning when David appears at the Commons he learns that Mr. Spenlow died suddenly the night before. Well that was convenient.

The next morning when David appears at the Commons he learns that Mr. Spenlow died suddenly the night before. Well that was convenient.Wasn't it, though? It would have been more convenient if he'd done his will first.

I 100% believe it that he didn't do it, though. I have a relative who was the sort of person who insured everything and crossed all the i's and dotted all the t's and emailed drafts of his will to his daughter to make sure she had a copy just in case, and then years later got sick with cancer for a whole year before it finally took him. And it turns out he'd never finalized and signed the will, even though he'd known he was deathly ill. People are so odd in what they are and aren't able to face.

Kim wrote: "Of course Miss Murdstone ending up with Dora, Mr. Murdstone being with her father, Mr. Micawber showing up from nowhere with Traddles living with him all seem a little too hard to believe too. And yet we believe it. "

Or, y'know. We just carry on anyway.

Could somebody please explain to me why Betsey Trotwood and Agnes Wickfield, neither of them fools, sit by and watch David being ridiculous about Dora--and not only do they never say a word about how maybe if she's too dim for him to share his troubles with then she is possibly not a good candidate to be his wife, but they actually encourage and assist him in pursuing her. I can see why Agnes might do this, because she might be afraid of looking jealous of Dora so maybe it's a comfort to condescend to her and call her a sweet little thing instead. But Betsey? When she knows what happens when you marry badly?

Could somebody please explain to me why Betsey Trotwood and Agnes Wickfield, neither of them fools, sit by and watch David being ridiculous about Dora--and not only do they never say a word about how maybe if she's too dim for him to share his troubles with then she is possibly not a good candidate to be his wife, but they actually encourage and assist him in pursuing her. I can see why Agnes might do this, because she might be afraid of looking jealous of Dora so maybe it's a comfort to condescend to her and call her a sweet little thing instead. But Betsey? When she knows what happens when you marry badly?Then again, Betsey does chant blind blind blind at David repeatedly, and maybe if he's too blind to pick up that there might be a little problem she's pointing to there, she figures there's no hope for him.

I am also considering the possibility that she sends him off to Canterbury while he's not allowed to see Dora because she hopes he'll reconnect with Agnes. Oh, well.

I'm just gonna put it out there (as the kids say) that this might be a better book without Little Em'ly and her uncle in it.

I'm just gonna put it out there (as the kids say) that this might be a better book without Little Em'ly and her uncle in it.

I think Martha might be more symbolic than a real person. She first appears in connection with Little Em'ly, foreshadowing her fall. Then now she appears moments before David meets Mr. Peggotty, and afterwards, she is fleeing not that far from them - and Mr. Peggotty doesn't notice her. I think she might be a means to show Em'ly and her actions without really writing those actions out. So first there is her fall, then there is Peggotty not noticing how near she is, and not seeing her run away right in front of his eyes. Could it be that Em'ly is so near too, and that Peggotty fails to see her in his search for her?

Julie, I wondered too why no one warned David for his mistakes. Perhaps that is because they are engaged already, and people who dive headfirst into unwise relationships tend to bite into their choices harder. It reminds me of my relationship with my ex at least - people tried to help me, but no one told me right in my face he was a bastard. Because they knew I already knew, and telling it to me that way wouldn't help. I must admit this feels the same way: David already knows she's a dimwitted, dull, spoiled little thing, but if they tell him so he will probably defend his choice by singing her praises. So they try to pile it up and let him make his own choice.

Julie, I wondered too why no one warned David for his mistakes. Perhaps that is because they are engaged already, and people who dive headfirst into unwise relationships tend to bite into their choices harder. It reminds me of my relationship with my ex at least - people tried to help me, but no one told me right in my face he was a bastard. Because they knew I already knew, and telling it to me that way wouldn't help. I must admit this feels the same way: David already knows she's a dimwitted, dull, spoiled little thing, but if they tell him so he will probably defend his choice by singing her praises. So they try to pile it up and let him make his own choice.

Julie wrote: "Could somebody please explain to me why Betsey Trotwood and Agnes Wickfield, neither of them fools, sit by and watch David being ridiculous about Dora--and not only do they never say a word about h..."

Hi Julie

I wonder if the answer is simply that many people, myself included, who should say something to any person, or even a best friend, don’t. Perhaps the reason is we fear we may anger and even lose theIr friendship. Perhaps it’s because we feel we will be able to help weather the storm at the side of our friend should they find themselves in trouble? Maybe even, we want to feel we were right and want to see the situation play itself out. Could it be we think our love will supersede anyone else’s? I’m guilty of all the above at one time or another.

In terms of the novel I think Dickens has to let the life of David play out to the end. Dickens must let David go through trials, heartache, loss, realization, reconciliation and discover joy and wholeness and full awareness before he can be judged as a human being. That judgement is whether he is a hero or not. The question of being a hero or not is the question David asks his readers at the beginning of the novel. I’m looking forward to our final discussion of David Copperfield where I hope we will all weight in on the question of whether David is a hero or not. Time will tell ... :-)

Hi Julie

I wonder if the answer is simply that many people, myself included, who should say something to any person, or even a best friend, don’t. Perhaps the reason is we fear we may anger and even lose theIr friendship. Perhaps it’s because we feel we will be able to help weather the storm at the side of our friend should they find themselves in trouble? Maybe even, we want to feel we were right and want to see the situation play itself out. Could it be we think our love will supersede anyone else’s? I’m guilty of all the above at one time or another.

In terms of the novel I think Dickens has to let the life of David play out to the end. Dickens must let David go through trials, heartache, loss, realization, reconciliation and discover joy and wholeness and full awareness before he can be judged as a human being. That judgement is whether he is a hero or not. The question of being a hero or not is the question David asks his readers at the beginning of the novel. I’m looking forward to our final discussion of David Copperfield where I hope we will all weight in on the question of whether David is a hero or not. Time will tell ... :-)

Jantine wrote: "I think Martha might be more symbolic than a real person. She first appears in connection with Little Em'ly, foreshadowing her fall. Then now she appears moments before David meets Mr. Peggotty, an..."

Jantine

I agree with your focus on Martha and Em’ly. They are linked in many ways from where they work to where they live and now to the choices they have made in life. Martha is more fully aware of the consequences and your comments about Peggotty are interesting. Martha is portrayed as a shadow, something that is present but without substance.

It will be interesting to see how Dickens continues this narrative thread in the coming chapters.

Jantine

I agree with your focus on Martha and Em’ly. They are linked in many ways from where they work to where they live and now to the choices they have made in life. Martha is more fully aware of the consequences and your comments about Peggotty are interesting. Martha is portrayed as a shadow, something that is present but without substance.

It will be interesting to see how Dickens continues this narrative thread in the coming chapters.

Peter wrote: "That judgement is whether he is a hero or not. The question of being a hero or not is the question David asks his readers at the beginning of the novel. I’m looking forward to our final discussion of David Copperfield where I hope we will all weight in on the question of whether David is a hero or not. Time will tell ... :-) "

Peter wrote: "That judgement is whether he is a hero or not. The question of being a hero or not is the question David asks his readers at the beginning of the novel. I’m looking forward to our final discussion of David Copperfield where I hope we will all weight in on the question of whether David is a hero or not. Time will tell ... :-) "I am also looking forward to this discussion!

Julie wrote: "I'm just gonna put it out there (as the kids say) that this might be a better book without Little Em'ly and her uncle in it."

Julie wrote: "I'm just gonna put it out there (as the kids say) that this might be a better book without Little Em'ly and her uncle in it."I agree with you there, Julie.

By the way, did any of you know that Robert Graves (of I Claudius fame) published a book entitled "The real David Copperfield"? He basically "removed" the parts of the book he felt were superfluous and restored the novel to its "natural length". It's on GR...as an audio tape. Go figure.

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/6...

Ulysse wrote: "By the way, did any of you know that Robert Graves (of I Claudius fame) published a book entitled "The real David Copperfield"? He basically "removed" the parts of the book he felt were superfluous and restored the novel to its "natural length".

Ulysse wrote: "By the way, did any of you know that Robert Graves (of I Claudius fame) published a book entitled "The real David Copperfield"? He basically "removed" the parts of the book he felt were superfluous and restored the novel to its "natural length".I did not know that, and how fascinating, and how bold of Graves! I find it hard to imagine re-writing Dickens, but I can also see why he felt he ought to.

Peter wrote: "Julie wrote: "Could somebody please explain to me why Betsey Trotwood and Agnes Wickfield, neither of them fools, sit by and watch David being ridiculous about Dora--and not only do they never say ..."

You are right, Peter: Most people keep their good advice to themselves for fear of spoiling a relationship. I used to be very different in that I never minced my words and surprised or not-so-much-surprised people with my view on their problems and how they could solve them, sometimes unasked. But then, I am a German, and as Jantine - as my neighbour - might be able to tell you, this is typical of my country-men. It's one of the things that contribute to our special reputation, and it's also one of the things I became aware of and put aside when I stayed in England for a longer time, quickly noticing that people did not take it in good grace, and right they were ;-)

But when you come to Germany, prepare yourselves for a lot of blunt, Nelly-know-it-all honesty from most people here.

You are right, Peter: Most people keep their good advice to themselves for fear of spoiling a relationship. I used to be very different in that I never minced my words and surprised or not-so-much-surprised people with my view on their problems and how they could solve them, sometimes unasked. But then, I am a German, and as Jantine - as my neighbour - might be able to tell you, this is typical of my country-men. It's one of the things that contribute to our special reputation, and it's also one of the things I became aware of and put aside when I stayed in England for a longer time, quickly noticing that people did not take it in good grace, and right they were ;-)

But when you come to Germany, prepare yourselves for a lot of blunt, Nelly-know-it-all honesty from most people here.

What I really liked about this week's instalment was that Dickens gave us some insight into how Uriah became so very 'umble. Unlike Quilp and some other of Dickens's earlier villains, the evil characters in David Copperfield are quite multi-faceted and psychologically believable.

We may not excuse Uriah with the knowledge we get about him, thanks to a matured Dickens, but the character becomes more realistic and understandable. Just imagine the pent-up aggression and vile vengefulness that may fester in Uriah all the time. I hope this is not considered a spoiler but a little later Uriah will say to David that 'umble people have eyes and see a lot - I think this sums up Uriah Heep pretty much: He is like some spider sitting in front of its web, watching, watching, watching ...

We may not excuse Uriah with the knowledge we get about him, thanks to a matured Dickens, but the character becomes more realistic and understandable. Just imagine the pent-up aggression and vile vengefulness that may fester in Uriah all the time. I hope this is not considered a spoiler but a little later Uriah will say to David that 'umble people have eyes and see a lot - I think this sums up Uriah Heep pretty much: He is like some spider sitting in front of its web, watching, watching, watching ...

Tristram wrote: "You are right, Peter: Most people keep their good advice to themselves for fear of spoiling a relationship. .."

I'm not sure why our comments so often remind me of something in my life, but here's another story. One day my sister called me and told me that the lady living next to us is having an affair. She heard it from her neighbor, I don't know where she heard it from. So she asked if I was going to tell my neighbor's husband and I said no, why would I do such a thing, and she told me she thought he had a right to know. This went on for weeks, she would call and ask "did you tell him yet?" and I would tell her I have no intention of ever telling him. Then one day she called and said never mind, she talked to her neighbor again and it turns out that it wasn't my neighbor but a different lady in a town near us who happened to have the same name. Now think of all the trouble that would have caused if I listened to her.

I'm not sure why our comments so often remind me of something in my life, but here's another story. One day my sister called me and told me that the lady living next to us is having an affair. She heard it from her neighbor, I don't know where she heard it from. So she asked if I was going to tell my neighbor's husband and I said no, why would I do such a thing, and she told me she thought he had a right to know. This went on for weeks, she would call and ask "did you tell him yet?" and I would tell her I have no intention of ever telling him. Then one day she called and said never mind, she talked to her neighbor again and it turns out that it wasn't my neighbor but a different lady in a town near us who happened to have the same name. Now think of all the trouble that would have caused if I listened to her.

Tristram wrote: "What I really liked about this week's instalment was that Dickens gave us some insight into how Uriah became so very 'umble. Unlike Quilp and some other of Dickens's earlier villains, the evil char..."

I liked Quilp for a villain. He was evil, knew he was evil, liked being evil, never acted any other way than evil, there was nothing sneaky, tricky or humble about him.

I liked Quilp for a villain. He was evil, knew he was evil, liked being evil, never acted any other way than evil, there was nothing sneaky, tricky or humble about him.

Kim wrote: "Tristram wrote: "You are right, Peter: Most people keep their good advice to themselves for fear of spoiling a relationship. .."

I'm not sure why our comments so often remind me of something in my..."

It's good that you kept out of this thing, Kim. Generally, I have found it very wise not to meddle with other people's affairs (pardon the pun). It makes life a lot easier.

I'm not sure why our comments so often remind me of something in my..."

It's good that you kept out of this thing, Kim. Generally, I have found it very wise not to meddle with other people's affairs (pardon the pun). It makes life a lot easier.

Kim wrote: "Tristram wrote: "What I really liked about this week's instalment was that Dickens gave us some insight into how Uriah became so very 'umble. Unlike Quilp and some other of Dickens's earlier villai..."

Yes, but you hardly meet someone like that in real life. He's more like a melodrama stage villain. There are quite some Uriah Heeps though.

Yes, but you hardly meet someone like that in real life. He's more like a melodrama stage villain. There are quite some Uriah Heeps though.

Tristram wrote: "Yes, but you hardly meet someone like that in real life. He's more like a melodrama stage villain. There are quite some Uriah Heeps though."

Very true. I have never met a Quilp, but I know some Uriah Heeps. I wonder what they would think if they knew I thought of them that way.

Very true. I have never met a Quilp, but I know some Uriah Heeps. I wonder what they would think if they knew I thought of them that way.

Tristram wrote: "But then, I am a German, and as Jantine - as my neighbour - might be able to tell you, this is typical of my country-men."

Oh yes, and mine, and I love that. I really had a hard time with all the 'social games' while staying in the UK - I much prefer the blunt telling how it is of Germans and Dutch. At least then I know where I stand with people, and I know I can be blunt in return without being (too) offensive. Which might happen quite a lot, I think everyone has a point where things boil over, and we just blurt out what's what. For me that point lies pretty low. Partly because of being autistic probably xD but as I've learned to appreciate, a huge part is simply because of being used to that.

And of course it are all very much over-generalisations. Still, while we Dutch and Germans are not rude, and the British are not beating around the bush all the time, there certainly is truth in that we are more blunt and direct, and they are more careful. So yes, about the Agnes et al. not saying anything, I also had the thought 'oh, how British! Perfectly splendid!'

Oh yes, and mine, and I love that. I really had a hard time with all the 'social games' while staying in the UK - I much prefer the blunt telling how it is of Germans and Dutch. At least then I know where I stand with people, and I know I can be blunt in return without being (too) offensive. Which might happen quite a lot, I think everyone has a point where things boil over, and we just blurt out what's what. For me that point lies pretty low. Partly because of being autistic probably xD but as I've learned to appreciate, a huge part is simply because of being used to that.

And of course it are all very much over-generalisations. Still, while we Dutch and Germans are not rude, and the British are not beating around the bush all the time, there certainly is truth in that we are more blunt and direct, and they are more careful. So yes, about the Agnes et al. not saying anything, I also had the thought 'oh, how British! Perfectly splendid!'

Being blunt. My dad's image just arrived in my head. My dad always had this habit of speaking before he thought which got worse as he got older. When he reached his nineties he was hitting his stride in bluntness. Dad hadn't been in church in years, he didn't feel like going out much anymore, and once or twice had become dizzy at church and had to be taken home, so by this time he wouldn't go anymore. So now and then someone from the church would stop in to check on him. One night I was with him when one of the ladies stopped. She came in saying "Hi Ken, how are you doing?" and I could tell he had no idea who she was. Which is what he said, "Who the hell are you?" "I'm Dorothy, don't you remember me? " He looks at her for a few seconds and says "boy you got old."

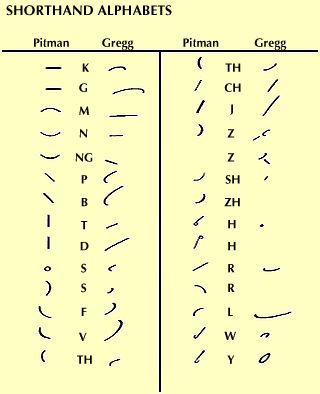

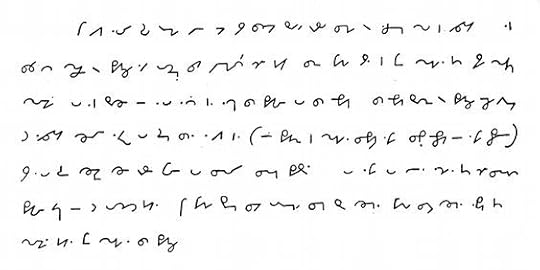

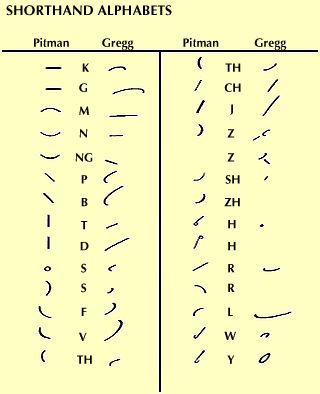

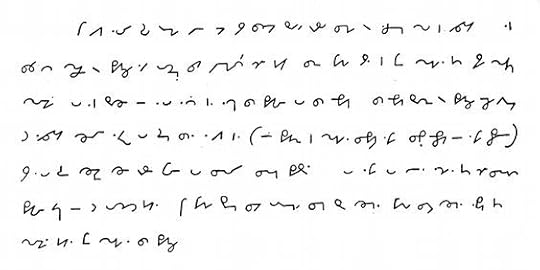

David says in Chapter 38:

"I bought an approved scheme of the noble art and mystery of stenography (which cost me ten and sixpence); and plunged into a sea of perplexity that brought me, in a few weeks, to the confines of distraction.

As I said above it brought to mind my own days of trying to write and then rewrite this stuff, I found an example of it:

So when you "learn" this stuff and write it down in letter form you get something like this:

When you try to translate all this back into English, if you're me you get nothing. Even though I wrote it I can't read the stuff.

"I bought an approved scheme of the noble art and mystery of stenography (which cost me ten and sixpence); and plunged into a sea of perplexity that brought me, in a few weeks, to the confines of distraction.

As I said above it brought to mind my own days of trying to write and then rewrite this stuff, I found an example of it:

So when you "learn" this stuff and write it down in letter form you get something like this:

When you try to translate all this back into English, if you're me you get nothing. Even though I wrote it I can't read the stuff.

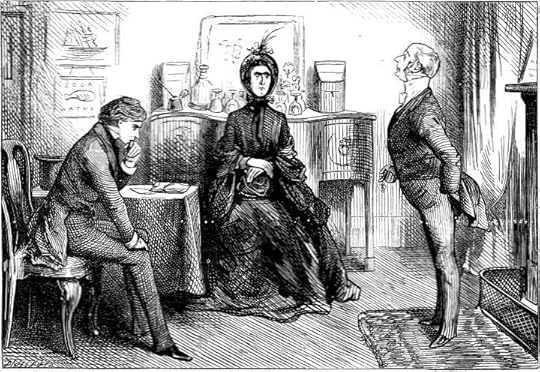

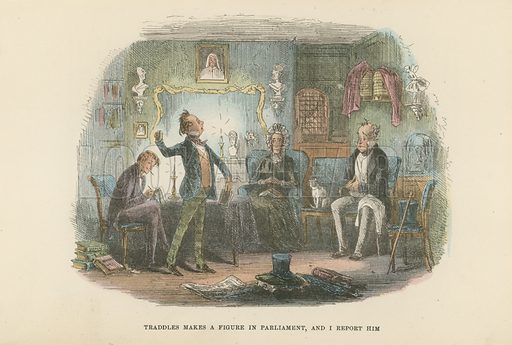

Traddles makes a figure in parliament and I report him

Chapter 38

Phiz

Commentary:

For the first illustration in the thirteenth monthly number, which was issued in May 1850 and comprises chapters 38 through 40, Phiz develops the relationship between the steady, hard-working young attorney and newspaper writer Tommy Traddles and the would-be parliamentary and legal short-hand reporter David Copperfield, whose determination to master the hieroglyphics of short-hand seems closely based on Dickens's own in the early 1830s, the moment that Phiz has realized is the following:

I should like to see such a Parliament anywhere else! My aunt and Mr. Dick represented the Government or the Opposition (as the case might be), and Traddles, with the assistance of Enfield’s Speakers, or a volume of parliamentary orations, thundered astonishing invectives against them. Standing by the table, with his finger in the page to keep the place, and his right arm flourishing above his head, Traddles, as Mr. Pitt, Mr. Fox, Mr. Sheridan, Mr. Burke, Lord Castlereagh, Viscount Sidmouth, or Mr. Canning, would work himself into the most violent heats, and deliver the most withering denunciations of the profligacy and corruption of my aunt and Mr. Dick; while I used to sit, at a little distance, with my notebook on my knee, fagging after him with all my might and main. The inconsistency and recklessness of Traddles were not to be exceeded by any real politician. He was for any description of policy, in the compass of a week; and nailed all sorts of colours to every denomination of mast. My aunt, looking very like an immovable Chancellor of the Exchequer, would occasionally throw in an interruption or two, as ‘Hear!’ or ‘No!’ or ‘Oh!’ when the text seemed to require it: which was always a signal to Mr. Dick (a perfect country gentleman) to follow lustily with the same cry. But Mr. Dick got taxed with such things in the course of his Parliamentary career, and was made responsible for such awful consequences, that he became uncomfortable in his mind sometimes. I believe he actually began to be afraid he really had been doing something, tending to the annihilation of the British constitution, and the ruin of the country.

Often and often we pursued these debates until the clock pointed to midnight, and the candles were burning down. The result of so much good practice was, that by and by I began to keep pace with Traddles pretty well, and should have been quite triumphant if I had had the least idea what my notes were about. But, as to reading them after I had got them, I might as well have copied the Chinese inscriptions of an immense collection of tea-chests, or the golden characters on all the great red and green bottles in the chemists’ shops!

There was nothing for it, but to turn back and begin all over again. It was very hard, but I turned back, though with a heavy heart, and began laboriously and methodically to plod over the same tedious ground at a snail’s pace; stopping to examine minutely every speck in the way, on all sides, and making the most desperate efforts to know these elusive characters by sight wherever I met them. I was always punctual at the office; at the Doctor’s too: and I really did work, as the common expression is, like a cart-horse. One day, when I went to the Commons as usual, I found Mr. Spenlow in the doorway looking extremely grave, and talking to himself. As he was in the habit of complaining of pains in his head—he had naturally a short throat, and I do seriously believe he over-starched himself—I was at first alarmed by the idea that he was not quite right in that direction; but he soon relieved my uneasiness.

The picture, like six others in Phiz's narrative-pictorial sequence for the serial, is organized around four characters in an interior setting. Once again, the scene occurs in David's sitting-room in his apartments on Buckingham Street, which has already been the backdrop for "We are disturbed in our cookery", "My Aunt astonishes me", and "Mr. Wickfield and his partner wait upon my Aunt". However, in this view of David's sitting room we see neither the window facing the river, nor the door leading to the stairs; however, visual continuity is provided by the mirror (centre) and Aunt Betsey's birdcages (right). The hassock, upon which her cat is perched in the earlier plate, is now front and centre, with a top hat upon it to suggest another member of Traddles' parliamentary audience. The other hat and cane likely are those carried by David in "My Aunt astonishes me" , so that the hat in the centre likely belongs to Traddles. Stacked by David's side are volumes of parliamentary reports and Hansard; the large volume on the floor near the hassock is not Enfield's Speaker, the text mentioned by Dickens, but J. H. Barrow's The Mirror of Parliament, a rival to Hansard's accounts of speeches in the Commons published from 1828 to 1843. The slender volume that Traddles is holding in his left hand as he gesticulates with his right is likely "a volume of parliamentary orations" from which his is declaiming in an oratorical manner that combines the styles of eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century parliamentarians Pitt, Fox, Sheridan, Canning, Castlereagh, and Sidmouth. The open newspaper on the floor to the left of centre (The Times?) may imply Traddles' attempt to integrate contemporary debates by politicians as reported in that London daily into his oratorical performance.

In the moment realized, short-hand writer David seems to be keeping pace with Traddles "pretty well" "with [his] note-book on [his] knee, fagging after him"; Phiz depicts him plausibly enough with a candle shedding light on a small pad of note-paper in his left hand, one pencil in his right, and an additional (sharpened) pencil at the ready in his mouth. Although he and Traddles seem to be enjoying themselves, Aunt Betsey as a facsimile of the Chancellor of the Exchequer and Mr. Dick as a country member are not, if one may judge by their glum expressions. A typical Phizzian touch is the inclusion of the classical busts to either side of the mirror suggest the parliamentary division of Tory and Whig, the captions beneath each denoting that the left-hand, large-nosed figure is the eloquent Greek orator Demosthenes and the right-hand,large-nosed figure is the brilliant Roman speaker and lawyer Cicero, to whose prowess Phiz implies that earnest Tommy Traddles aspires.

The scene may be based in part on Dickens's recollections about how he attempted to jot down parliamentary-style mock debates enacted by his parents, Aunt Betsey and Mr. Dick in this illustration standing in for Elizabeth and John Dickens. Although he had been warned, like David, that learning short hand could take as long as three years, Dickens mastered the system in as many months, recording cases in the courts such as Doctors' Commons and the reform-based debates in the House of Commons. Utilizing the short-hand self-help text Brachygraphy, or an Easy and Compendious System of Shorthand, through the same perseverance as David's here Dickens became highly proficient at the Gurney method, the same system learnt by his father and his uncle: "a few years later he was generally credited with being the best shorthand reporter in Parliament". As his parents moved house regularly, like the Micawbers, to evade their creditors, Dickens sometimes rented rooms closer to where he worked as a shorthand writer, including the rooms in York House in Buckingham Street and later in Cecil Street, no doubt because of the fact that these addresses were more convenient for his work in the House of Commons as much as for the absence of space in whatever temporary encampment the Dickens family had established.

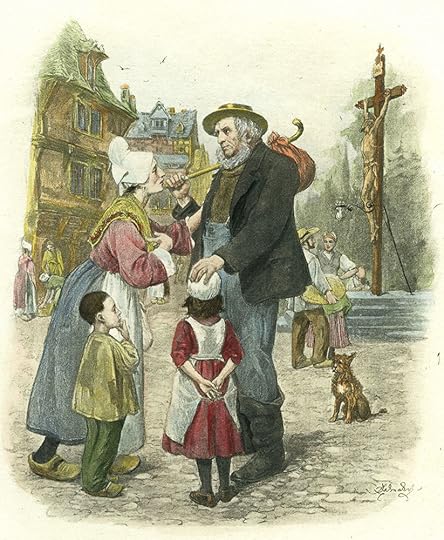

"You have heard Miss Murdstone," said Mr. Spenlow, turning to me.

Chapter 38

Fred Barnard

1872 Household Edition

Text Illustrated:

‘On my return to Norwood, after the period of absence occasioned by my brother’s marriage,’ pursued Miss Murdstone in a disdainful voice, ‘and on the return of Miss Spenlow from her visit to her friend Miss Mills, I imagined that the manner of Miss Spenlow gave me greater occasion for suspicion than before. Therefore I watched Miss Spenlow closely.’

Dear, tender little Dora, so unconscious of this Dragon’s eye!

‘Still,’ resumed Miss Murdstone, ‘I found no proof until last night. It appeared to me that Miss Spenlow received too many letters from her friend Miss Mills; but Miss Mills being her friend with her father’s full concurrence,’ another telling blow at Mr. Spenlow, ‘it was not for me to interfere. If I may not be permitted to allude to the natural depravity of the human heart, at least I may—I must—be permitted, so far to refer to misplaced confidence.’

Mr. Spenlow apologetically murmured his assent.

‘Last evening after tea,’ pursued Miss Murdstone, ‘I observed the little dog starting, rolling, and growling about the drawing-room, worrying something. I said to Miss Spenlow, “Dora, what is that the dog has in his mouth? It’s paper.” Miss Spenlow immediately put her hand to her frock, gave a sudden cry, and ran to the dog. I interposed, and said, “Dora, my love, you must permit me.”’

Oh Jip, miserable Spaniel, this wretchedness, then, was your work!

‘Miss Spenlow endeavoured,’ said Miss Murdstone, ‘to bribe me with kisses, work-boxes, and small articles of jewellery—that, of course, I pass over. The little dog retreated under the sofa on my approaching him, and was with great difficulty dislodged by the fire-irons. Even when dislodged, he still kept the letter in his mouth; and on my endeavouring to take it from him, at the imminent risk of being bitten, he kept it between his teeth so pertinaciously as to suffer himself to be held suspended in the air by means of the document. At length I obtained possession of it. After perusing it, I taxed Miss Spenlow with having many such letters in her possession; and ultimately obtained from her the packet which is now in David Copperfield’s hand.’

Here she ceased; and snapping her reticule again, and shutting her mouth, looked as if she might be broken, but could never be bent.

‘You have heard Miss Murdstone,’ said Mr. Spenlow, turning to me. ‘I beg to ask, Mr. Copperfield, if you have anything to say in reply?’

The picture I had before me, of the beautiful little treasure of my heart, sobbing and crying all night—of her being alone, frightened, and wretched, then—of her having so piteously begged and prayed that stony-hearted woman to forgive her—of her having vainly offered her those kisses, work-boxes, and trinkets—of her being in such grievous distress, and all for me—very much impaired the little dignity I had been able to muster. I am afraid I was in a tremulous state for a minute or so, though I did my best to disguise it.

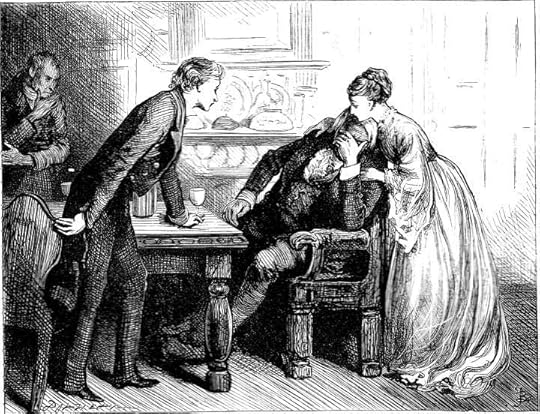

"Papa, you are not well. Come with me!"

Chapter 39

Fred Barnard

1872 Household Edition

Text Illustrated:

‘Oh, Trotwood, Trotwood!’ exclaimed Mr. Wickfield, wringing his hands. ‘What I have come down to be, since I first saw you in this house! I was on my downward way then, but the dreary, dreary road I have traversed since! Weak indulgence has ruined me. Indulgence in remembrance, and indulgence in forgetfulness. My natural grief for my child’s mother turned to disease; my natural love for my child turned to disease. I have infected everything I touched. I have brought misery on what I dearly love, I know—you know! I thought it possible that I could truly love one creature in the world, and not love the rest; I thought it possible that I could truly mourn for one creature gone out of the world, and not have some part in the grief of all who mourned. Thus the lessons of my life have been perverted! I have preyed on my own morbid coward heart, and it has preyed on me. Sordid in my grief, sordid in my love, sordid in my miserable escape from the darker side of both, oh see the ruin I am, and hate me, shun me!’

He dropped into a chair, and weakly sobbed. The excitement into which he had been roused was leaving him. Uriah came out of his corner.

‘I don’t know all I have done, in my fatuity,’ said Mr. Wickfield, putting out his hands, as if to deprecate my condemnation. ‘He knows best,’ meaning Uriah Heep, ‘for he has always been at my elbow, whispering me. You see the millstone that he is about my neck. You find him in my house, you find him in my business. You heard him, but a little time ago. What need have I to say more!’

‘You haven’t need to say so much, nor half so much, nor anything at all,’ observed Uriah, half defiant, and half fawning. ‘You wouldn’t have took it up so, if it hadn’t been for the wine. You’ll think better of it tomorrow, sir. If I have said too much, or more than I meant, what of it? I haven’t stood by it!’

The door opened, and Agnes, gliding in, without a vestige of colour in her face, put her arm round his neck, and steadily said, ‘Papa, you are not well. Come with me!’

He laid his head upon her shoulder, as if he were oppressed with heavy shame, and went out with her. Her eyes met mine for but an instant, yet I saw how much she knew of what had passed.

‘I didn’t expect he’d cut up so rough, Master Copperfield,’ said Uriah. ‘But it’s nothing. I’ll be friends with him tomorrow. It’s for his good. I’m umbly anxious for his good.’

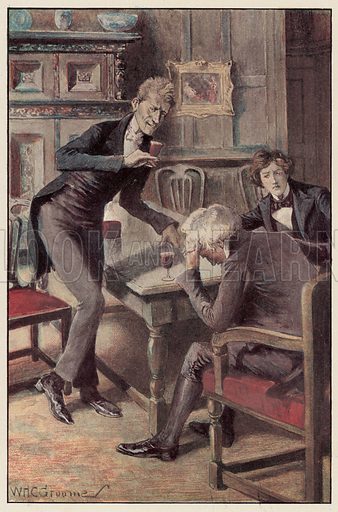

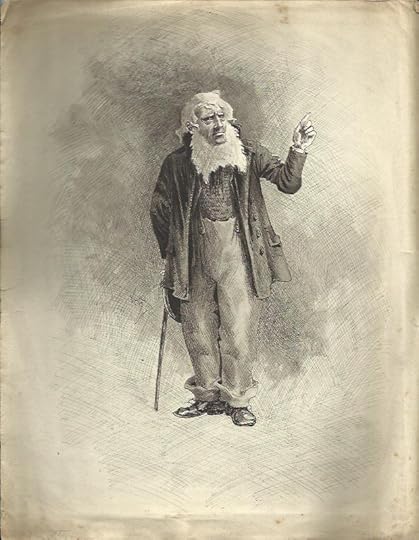

"What's the matter?" said Uriah.

Chapter 39

William Henry Charles Groome

1910

Text Illustrated:

Spare me from ever again hearing such a cry, as that with which her father rose up from the table! ‘What’s the matter?’ said Uriah, turning of a deadly colour. ‘You are not gone mad, after all, Mr. Wickfield, I hope? If I say I’ve an ambition to make your Agnes my Agnes, I have as good a right to it as another man. I have a better right to it than any other man!’

I had my arms round Mr. Wickfield, imploring him by everything that I could think of, oftenest of all by his love for Agnes, to calm himself a little. He was mad for the moment; tearing out his hair, beating his head, trying to force me from him, and to force himself from me, not answering a word, not looking at or seeing anyone; blindly striving for he knew not what, his face all staring and distorted—a frightful spectacle.

I conjured him, incoherently, but in the most impassioned manner, not to abandon himself to this wildness, but to hear me. I besought him to think of Agnes, to connect me with Agnes, to recollect how Agnes and I had grown up together, how I honoured her and loved her, how she was his pride and joy. I tried to bring her idea before him in any form; I even reproached him with not having firmness to spare her the knowledge of such a scene as this. I may have effected something, or his wildness may have spent itself; but by degrees he struggled less, and began to look at me—strangely at first, then with recognition in his eyes. At length he said, ‘I know, Trotwood! My darling child and you—I know! But look at him!’

He pointed to Uriah, pale and glowering in a corner, evidently very much out in his calculations, and taken by surprise.

‘Look at my torturer,’ he replied. ‘Before him I have step by step abandoned name and reputation, peace and quiet, house and home.’

‘I have kept your name and reputation for you, and your peace and quiet, and your house and home too,’ said Uriah, with a sulky, hurried, defeated air of compromise. ‘Don’t be foolish, Mr. Wickfield. If I have gone a little beyond what you were prepared for, I can go back, I suppose? There’s no harm done.’

‘I looked for single motives in everyone,’ said Mr. Wickfield, ‘and I was satisfied I had bound him to me by motives of interest. But see what he is—oh, see what he is!’

‘You had better stop him, Copperfield, if you can,’ cried Uriah, with his long forefinger pointing towards me. ‘He’ll say something presently—mind you!—he’ll be sorry to have said afterwards, and you’ll be sorry to have heard!’

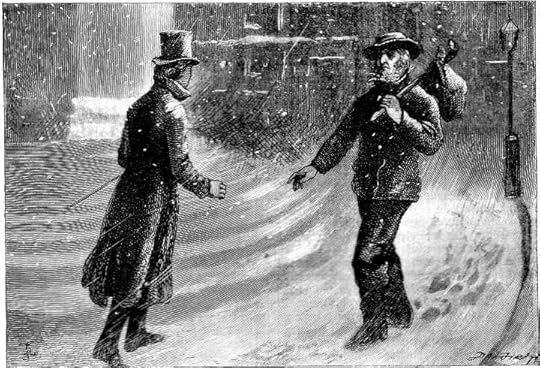

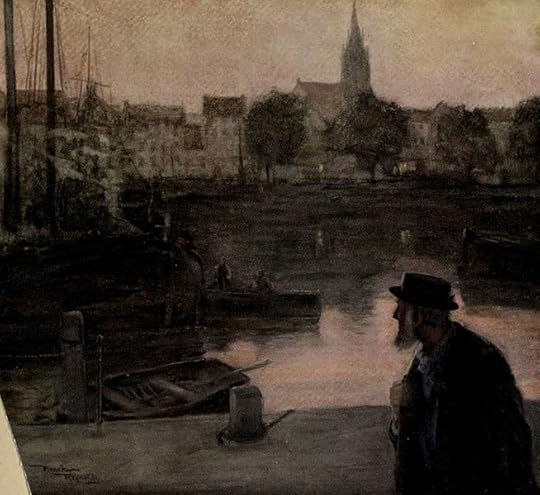

"I stood face to face with Mr. Peggotty!"

Chapter 40

Fred Barnard

1872 Household Edition

Text Illustrated:

It had been a bitter day, and a cutting north-east wind had blown for some time. The wind had gone down with the light, and so the snow had come on. It was a heavy, settled fall, I recollect, in great flakes; and it lay thick. The noise of wheels and tread of people were as hushed, as if the streets had been strewn that depth with feathers.

My shortest way home,—and I naturally took the shortest way on such a night—was through St. Martin’s Lane. Now, the church which gives its name to the lane, stood in a less free situation at that time; there being no open space before it, and the lane winding down to the Strand. As I passed the steps of the portico, I encountered, at the corner, a woman’s face. It looked in mine, passed across the narrow lane, and disappeared. I knew it. I had seen it somewhere. But I could not remember where. I had some association with it, that struck upon my heart directly; but I was thinking of anything else when it came upon me, and was confused.

On the steps of the church, there was the stooping figure of a man, who had put down some burden on the smooth snow, to adjust it; my seeing the face, and my seeing him, were simultaneous. I don’t think I had stopped in my surprise; but, in any case, as I went on, he rose, turned, and came down towards me. I stood face to face with Mr. Peggotty!

Commentary:

Barnard depicts David Copperfield as slight with his face seen in profile and so cross-hatched as to be unrecognizable, but he gives us a stalwart Mr. Peggotty. Whereas the stiff wind that sweeps through the illustration from left to right propels David forward at an angle, Dan'l Peggotty remains unaffected as he extends his right hand toward to grasp David's. In the background, the blinding snow renders indistinct the steps of the church portico in the Strand, and the gas lamp lacks any power to illuminate the scene, but the Wanderer presses on, as fate has assigned him a duty he will not abandon, no matter what the weather or hardships he must endure. Thus, without the benefit of the kind of background detail and costume elements that Phiz loved to elaborate, Barnard has communicated the patriarchal Dan'l Peggotty's essential steadfastness.

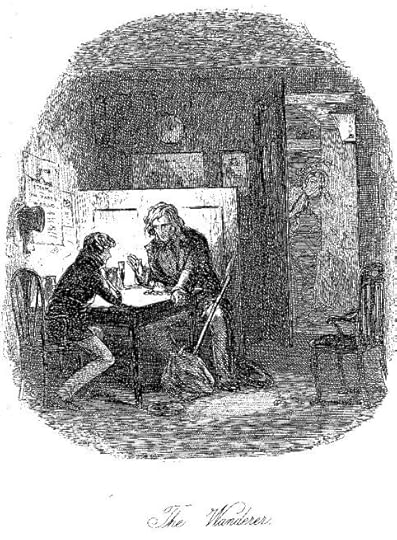

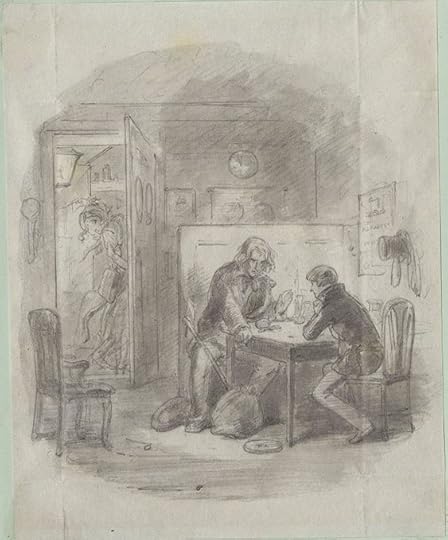

The Wanderer

Chapter 40

Phiz

Commentary:

In "The Wanderer," the second illustration for the thirteenth monthly number (chapters 38, 39, and 40), Phiz reverts to the plot involving Little Em'ly's abduction by Steerforth, keeping readers in suspense about the outcome of both David's courting the recently orphaned Dora Spenlow, and Heep's growing influence over Mr. Wickfield as he intimates that he intends marry Agnes. The melodramatic moment realized in the second illustration for May 1850, is this as Dan'l Peggotty recounts to David his determined pursuit of the couple overseas:

‘When she was—lost,’ said Mr. Peggotty, ‘I know’d in my mind, as he would take her to them countries. I know’d in my mind, as he’d have told her wonders of ‘em, and how she was to be a lady theer, and how he got her to listen to him fust, along o’ sech like. When we see his mother, I know’d quite well as I was right. I went across-channel to France, and landed theer, as if I’d fell down from the sky.’

I saw the door move, and the snow drift in. I saw it move a little more, and a hand softly interpose to keep it open.

‘I found out an English gen’leman as was in authority,’ said Mr. Peggotty, ‘and told him I was a-going to seek my niece. He got me them papers as I wanted fur to carry me through—I doen’t rightly know how they’re called—and he would have give me money, but that I was thankful to have no need on. I thank him kind, for all he done, I’m sure! “I’ve wrote afore you,” he says to me, “and I shall speak to many as will come that way, and many will know you, fur distant from here, when you’re a-travelling alone.” I told him, best as I was able, what my gratitoode was, and went away through France.’

‘Alone, and on foot?’ said I.

‘Mostly a-foot,’ he rejoined; ‘sometimes in carts along with people going to market; sometimes in empty coaches. Many mile a day a-foot, and often with some poor soldier or another, travelling to see his friends. I couldn’t talk to him,’ said Mr. Peggotty, ‘nor he to me; but we was company for one another, too, along the dusty roads.’

I should have known that by his friendly tone.

‘When I come to any town,’ he pursued, ‘I found the inn, and waited about the yard till someone turned up (someone mostly did) as know’d English. Then I told how that I was on my way to seek my niece, and they told me what manner of gentlefolks was in the house, and I waited to see any as seemed like her, going in or out. When it warn’t Em’ly, I went on agen. By little and little, when I come to a new village or that, among the poor people, I found they know’d about me. They would set me down at their cottage doors, and give me what-not fur to eat and drink, and show me where to sleep; and many a woman, Mas’r Davy, as has had a daughter of about Em’ly’s age, I’ve found a-waiting fur me, at Our Saviour’s Cross outside the village, fur to do me sim’lar kindnesses. Some has had daughters as was dead. And God only knows how good them mothers was to me!’

It was Martha at the door. I saw her haggard, listening face distinctly. My dread was lest he [Mr. Peggotty] should turn his head, and see her too.

The second illustration for May 1850 contains a smaller number of those visual symbols such as portraits, biblical scenes, and landscapes that habitually serve as Phiz's commentaries on the characters and their circumstances in the narrative-pictorial sequence for David Copperfield, but it successfully communicates the air of suspense created by Martha's attempting to overhear Mr. Peggotty's reading to David the letters from Em'ly on the Continent. As the text explains before the reader arrives at this illustration, the scene takes place in one of the public-rooms adjacent to the stable yard of the Golden Cross, the coaching inn where David by sheer Dickensian coincidence encountered Steerforth after leaving school in Canterbury on his way to visit the Peggottys in Yarmouth (November 1849, the seventh monthly number).

Now chance once again brings David together with another esteemed figure from his past. On his way home from Doctors' Commons one snowy evening, David catches sight of Martha Endell before meeting an outwardly changed Dan'l Peggotty in Saint Martin's Lane. David judges from his weather-beaten visage and long, greying hair that Mr. Peggotty has pursued his niece and her dissolute paramour "through all varieties of weather"; although thus changed and as yet unsuccessful in catching up with the couple, the uncle has maintained his positive outlook and "stedfastness of purpose". To maintain a focus appropriate to Peggotty's position in the text, Phiz has situated the traveller in centre of the vertical illustration, in a pool of light amidst the shadowy furnishings of the public-room late in the evening, with Martha up right and David left of centre. Mr. Peggotty is not, as we might reasonably expect, tanned, and he seems much thinner than in the last scene in "Mr. Peggotty and Mrs. Steerforth" in the eleventh (March) number. The wanderer's bag, staff, and hat, which Dickens mentioned in chapter 40, are consistent with those in that previous illustration and so provide visual continuity. The bag, however, is much bigger and seems darker, while their owner, despite the similarity in his trousers and shoes, wears a middle-class coat. His hair has grown longer and is now white, and he no longer wears a beard. Indeed, despite his continuing "stedfastness of purpose" the wanderer seems almost another man, whereas David is still the same young gentleman of middle stature, his middle-class respectability proclaimed by his hat, hanging on a peg beside him.

To remain consistent with Dickens's description, Phiz has depicted the wanderer with his back to the partially opened door after a server has brought his hot ale. Dan'l Peggotty briefly recounts how his pursuit of Em'ly and Steerforth has taken him to what Dickens probably intends to be a description of the coast of southern France and northern Italy, "where the sea got to be dark blue, . . . a- shining in the sun", the locale being described by Mr. Peggotty as "where the flowers is always a blowing, and the country bright". Dickens himself had become familiar with that same region in 1844-45 when he took his family on an extended sabbatical to Genoa.

The precise moment captured in the etching is suggested by the door's blowing open to admit the snowy breeze as Martha curiously peers in, apparently attempting to overhear Mr. Peggotty's account of his fruitless search on the Mediterranean coast and in the Swiss mountains. Although Phiz has made her bonnet look a little wind-blown, he has failed to make her face "haggard". Phiz illuminates her face by a gas lantern in the stable yard that Dickens does not mention. Dan'l Peggotty has not yet broken down under the force of emotion and covered his face. Thus, Phiz's Peggotty seems more stoic and composed than the text's.

Since this coaching inn is not in the general vicinity of the docks, the poster advertising "steamers for all parts of the world" with the profile of a paddle-wheeler of the type introduced in the 1820s (screw-propeller-driven vessels not coming in general use for either cross-channel and trans-Atlantic shipping until 1870), like the map of the hemispheres in the background, above Mr. Peggotty's head, seems intended to comment on the extent to which the devoted uncle is prepared to prosecute his search. Although he has met David in the early evening, the clock's being set at ten minutes to eleven implies that hours have transpired in conversation. The empty chair to the right implies both his absent niece and Martha's silent presence, not detected by Dan'l Peggotty, but noted by his interlocutor.

Kim wrote: "I do not understand this as an illustration of David Copperfield at all:

Kim wrote: "I do not understand this as an illustration of David Copperfield at all:"

I don't either!!

I've just gotten through this thread and it is time to start reading the next section. I am keeping up but just very slowly. I enjoyed all the comments.

I've just gotten through this thread and it is time to start reading the next section. I am keeping up but just very slowly. I enjoyed all the comments.

Jantine wrote: "And of course it are all very much over-generalisations. Still, while we Dutch and Germans are not rude, and the British are not beating around the bush all the time, there certainly is truth in that we are more blunt and direct, and they are more careful. So yes, about the Agnes et al. not saying anything, I also had the thought 'oh, how British! Perfectly splendid!'"

Jantine wrote: "And of course it are all very much over-generalisations. Still, while we Dutch and Germans are not rude, and the British are not beating around the bush all the time, there certainly is truth in that we are more blunt and direct, and they are more careful. So yes, about the Agnes et al. not saying anything, I also had the thought 'oh, how British! Perfectly splendid!'"I find this very funny because nearly every time I have a British student in discussion class, all the American students panic at how direct and blunt they are. So I guess Americans are even further toward the end of the speak-no-evil spectrum.

Julie wrote: "Jantine wrote: "And of course it are all very much over-generalisations. Still, while we Dutch and Germans are not rude, and the British are not beating around the bush all the time, there certainl..."

Julie wrote: "Jantine wrote: "And of course it are all very much over-generalisations. Still, while we Dutch and Germans are not rude, and the British are not beating around the bush all the time, there certainl..."Well, we Americans may not be as blunt and direct in most instances except as you can see now in our politics. I am embarrassed how our nation is so rude and divided in our politics.

Kim wrote: "

Traddles makes a figure in parliament and I report him

Chapter 38

Phiz

Commentary:

For the first illustration in the thirteenth monthly number, which was issued in May 1850 and comprises chap..."

Kim

How delightful. I wonder if Dickens actually saw himself represented in this illustration by Browne. It is evident that this novel is the most autobiographical. With this illustration would Dickens and his readers actually get a glimpse or representation of Dickens at work? Could that partially explain the large mirror? Was Browne saying “here’s a look at yourself as a parliamentary reporter?”

Traddles makes a figure in parliament and I report him

Chapter 38

Phiz

Commentary:

For the first illustration in the thirteenth monthly number, which was issued in May 1850 and comprises chap..."

Kim

How delightful. I wonder if Dickens actually saw himself represented in this illustration by Browne. It is evident that this novel is the most autobiographical. With this illustration would Dickens and his readers actually get a glimpse or representation of Dickens at work? Could that partially explain the large mirror? Was Browne saying “here’s a look at yourself as a parliamentary reporter?”

Kim wrote: "

"I stood face to face with Mr. Peggotty!"

Chapter 40

Fred Barnard

1872 Household Edition

Text Illustrated:

It had been a bitter day, and a cutting north-east wind had blown for some time. Th..."

Yes. This is a wonderful illustration. We have David wearing a top hat, an indication of his rank in society. Peggotty’s hat clearly indicates his working class status. We have David with a walking stick which again is a subtle sign of his social status. To contrast this Peggotty has a bundle attached to a pole over his shoulder. This also shows the social rank of Peggotty. To me, as stated in the Barnard illustration’s commentary, the fact that both men have their right arms extended forward is a clear suggestion that the two are about to shake hands. These men are, in fact, equals.

The shaking of hands is a clear indication that while the two men may appear to be of separate classes the most important fact is they are friends who recognize their common traits as humans who share a common past and a journey through life. Barnard has created a vanishing point in his illustration that is represented by the street over David’s shoulder. Both men are on a journey. David's journey was to find his way to his aunt’s house and thus his family. Peggotty’s present journey is to find Little Em’ly and thus reunite her with her family.

The final success or failure of their separate journeys await the reader in their journey through the next chapters.

"I stood face to face with Mr. Peggotty!"

Chapter 40

Fred Barnard

1872 Household Edition

Text Illustrated:

It had been a bitter day, and a cutting north-east wind had blown for some time. Th..."

Yes. This is a wonderful illustration. We have David wearing a top hat, an indication of his rank in society. Peggotty’s hat clearly indicates his working class status. We have David with a walking stick which again is a subtle sign of his social status. To contrast this Peggotty has a bundle attached to a pole over his shoulder. This also shows the social rank of Peggotty. To me, as stated in the Barnard illustration’s commentary, the fact that both men have their right arms extended forward is a clear suggestion that the two are about to shake hands. These men are, in fact, equals.

The shaking of hands is a clear indication that while the two men may appear to be of separate classes the most important fact is they are friends who recognize their common traits as humans who share a common past and a journey through life. Barnard has created a vanishing point in his illustration that is represented by the street over David’s shoulder. Both men are on a journey. David's journey was to find his way to his aunt’s house and thus his family. Peggotty’s present journey is to find Little Em’ly and thus reunite her with her family.

The final success or failure of their separate journeys await the reader in their journey through the next chapters.

Kim wrote: "

The Wanderer

Chapter 40

Phiz

Commentary:

In "The Wanderer," the second illustration for the thirteenth monthly number (chapters 38, 39, and 40), Phiz reverts to the plot involving Little Em'l..."

Ah, yes. At the very end of the very detailed commentary the

empty chair is mentioned. To me, the empty chair is the perfect touch in the illustration.

Indeed, poor Em’ly. :-)

The Wanderer

Chapter 40

Phiz

Commentary:

In "The Wanderer," the second illustration for the thirteenth monthly number (chapters 38, 39, and 40), Phiz reverts to the plot involving Little Em'l..."

Ah, yes. At the very end of the very detailed commentary the

empty chair is mentioned. To me, the empty chair is the perfect touch in the illustration.

Indeed, poor Em’ly. :-)

Kim wrote: "

Original sketch by Phiz"

The original sketches. How great! To see them is to see the origin of what will appear in the novel. Heck! To me it’s like Carter looking into King Tut’s tomb.

As for the signed copy of the novel to Brooks of Sheffield, what a great anecdote. Thanks.

Original sketch by Phiz"

The original sketches. How great! To see them is to see the origin of what will appear in the novel. Heck! To me it’s like Carter looking into King Tut’s tomb.

As for the signed copy of the novel to Brooks of Sheffield, what a great anecdote. Thanks.

Julie wrote: "Jantine wrote: "And of course it are all very much over-generalisations. Still, while we Dutch and Germans are not rude, and the British are not beating around the bush all the time, there certainl..."

When I lived in England, I found that British people were generally more given to social phrases and politeness than Germans. They tend to say things like, "One of these days, you must come over to see us at my place", more quickly than Germans. When a German says this, he will usually have it followed up with an invitation - but then Germans do not invite people so soon to their own homes. And so, they won't say it so quickly.

When I lived in England, I found that British people were generally more given to social phrases and politeness than Germans. They tend to say things like, "One of these days, you must come over to see us at my place", more quickly than Germans. When a German says this, he will usually have it followed up with an invitation - but then Germans do not invite people so soon to their own homes. And so, they won't say it so quickly.

Tristram wrote: "When a German says this, he will usually have it followed up with an invitation"

When a German says that it is all one word.

When a German says that it is all one word.

Julie wrote: "I'm just gonna put it out there (as the kids say) that this might be a better book without Little Em'ly and her uncle in it."

Little Em'ly and her uncle seem like something odd thrown in there here and there to me. Without them though we wouldn't have Steerforth, at least not the Steerforth we ended up with. I wonder what the book would be like if Em'ly would just have married Ham and had lots of children and that would be the end of her? Where would Steerforth be now?

Little Em'ly and her uncle seem like something odd thrown in there here and there to me. Without them though we wouldn't have Steerforth, at least not the Steerforth we ended up with. I wonder what the book would be like if Em'ly would just have married Ham and had lots of children and that would be the end of her? Where would Steerforth be now?

The wandering around all over that Mr. Peggotty does seems very strange to me. Wouldn't you have to have some sort of clue as to where a person could be before you go off in search of them? Does he even have any idea which country she is in? Steerforth can afford to take her anywhere I imagine, so if they are on some tropical island, how is Mr. Peggoty going to find her there?

Peggoty Searching for Little Emily

Signed "F. Barnard"

1912

The principal illustrator of Chapman and Hall's 1870s Household Edition, Fred Barnard, contracted with Cassell, Petter, and Galpin to produce his first series of six extra illustrations, "Character Sketches from Dickens," in lithograph including portraits of some of Dickens's best-loved early characters. Dan'l Peggoty was in the second edition.

Just my own thought, this does not look like a Fred Barnard illustration to me, much more like a Darley, but I will take their word for it. Also, I find it very creepy there really is a body on that cross.

I just found this:

Third Cliff resident Lyle Nyberg had been working on a biography of George Lunt when he came upon the unique piece of Peggotty’s past.

An artist from Hawaii and an aspiring author enjoyed a walk along Peggotty Beach on a recent afternoon.

Then they discussed what could have inspired someone to give it that name, and suspect a connection to famed author Charles Dickens.

Third Cliff resident Lyle Nyberg had been working on a biography of George Lunt, and reached out to Toni Martin, a Lunt descendant as part of his research. Martin recently visited Nyberg and they discussed whether her grandmother, Francesca, could have given Peggotty Beach its name, as history seemed to suggest.

After Martin left Scituate, Nyberg discovered it was unlikely Francesca named the beach. A travel guide from 1873 references the name, he said. That would have been before the Lunts moved to Scituate and Francesca would have only been about 4 years old.

But the likely inspiration for the name that Nyberg and Martin discussed seems even more true, he said.

One of the homes at Third Cliff at the time was commonly known as “Bleak House,” which shared its name with a Dickens novel published in 1853, not long before the travel guide, and any avid reader would also know about Dickens’ “David Copperfield.” Published in 1849, the novel included character named Clara Peggotty, a loyal nurse and friend of the title character who is called mostly by her surname.

There’s also Mr. Peggotty, Clara’s brother who has a lot in common with a group of people who call Scituate home today: He is a fisherman who specializes in lobsters.

Previously, it had been Bassing Cove, likely named for the fish that could be caught there, Nyberg said. The former name is still used on some old records.

On a seasonably cool summer afternoon that Martin had to view Peggotty, she fell in love with the town her family had once known. The somber colors were a stark contrast to the beaches at the artist’s Hawaiian home, but the subtle beauty overcame her.

Francesca Lunt, born in 1869, lived in Scituate from 1877 until around 1895, Nyberg explained, offering the family history.

Her parents, George and Adeline, were both poets and her father was a prominent Massachusetts politician, lawyer and newspaperman. After the Civil War, George retired to Scituate, where the family lived at “Bayside,” a historic house later named The Meeting House Inn that stood at what is now the corner of Kent Street and Meeting House Lane in a part of Third Cliff that overlooks Peggotty.

Francesca was George’s daughter from his third marriage, Nyberg said.

“Francesca was an outgoing, perhaps headstrong young woman, supposedly a beauty,” he said, referring again to his research before adding, “She loved to sing and, I believe, write poetry. She and her mother visited the U.S. Life Saving Service station on Fourth Cliff to hand out books for the men stationed there to read.”

In conducting research for his biography of George, Nyberg found and started conversations with Martin.

She was planning a trip to the East Coast where she has family and so arranged a visit to Scituate to see the beach for herself.