The Old Curiosity Club discussion

This topic is about

David Copperfield

David Copperfield

>

DC, Chp. 47-50

Chapter 48, which is entitled „Domestic“ gives us further insight into David’s not quite satisfactory household matters. It begins with a little remark on how an author feels when his work is praised, and I think that it is Dickens himself who is talking here and who was quite aware of his merits as a writer – so much so that he arose the grudge of some of his contemporaries, like Trollope, who was also a cool writer, but not quite as cool as Dickens 😉

”I was not stunned by the praise which sounded in my ears, notwithstanding that I was keenly alive to it, and thought better of my own performance, I have little doubt, than anybody else did. It has always been in my observation of human nature, that a man who has any good reason to believe in himself never flourishes himself before the faces of other people in order that they may believe in him. For this reason, I retained my modesty in very self-respect; and the more praise I got, the more I tried to deserve.”

This seems like a man who is so much convinced of himself that he does not even deign to blow his own whistle, whereas he would not overstress his show of modesty. The narrator goes on like this:

”Having some foundation for believing, by this time, that nature and accident had made me an author, I pursued my vocation with confidence. Without such assurance I should certainly have left it alone, and bestowed my energy on some other endeavour. I should have tried to find out what nature and accident really had made me, and to be that, and nothing else.”

I find these words quite puzzling because to me they seem to imply that had David not met with (immediate?) success as a writer, he would have left off writing and turned to another field of action – and maybe this is even true of Dickens himself, who hit the public nerve with his first novel and who shaped the following novels closely to what he regarded as the public’s wishes – e.g. by introducing the America episodes into Martin Chuzzlewit when he noticed a waning interest in his novel. I have always thought that an author would feel in himself a calling regardless of what the public may think about his outpourings – which would, indeed, explain for but not excuse a lot of outpourings – and that in the worst case he would write for the drawer (as the German phrase goes), with a view to posterity. Here, however, David/Dickens seems to regard the calling – “nature” – as no more powerful an incentive to writing than “accident”, i.e. the reception of his novels by the public.

After these remarks on his successes as an author, David gives a humorous description of some further mishaps that befall their household, and after the plodding preceding chapter I welcomed the comic relief here even though I was appalled to learn that the page was going to be deported for stealing a gold watch, which shows how strict the law was at that time. David’s remonstrance that they must take a more serious outlook on housekeeping because it was not only themselves they were harming but also others by encouraging them to take illegal advantage of them – an interesting thought, by the way –, is met by poor Dora in her usual way, i.e. turning a matter-of-fact argument into an invective against herself – as if she had stolen the watch or told fibs – and so David tries to counter Dora’s childishness with increased seriousness and matter-of-factness. Even Shakespeare is used as a means of educating Dora, but to no avail. Finally it occurs to David, and this conclusion made me laugh out loud,

”that perhaps Dora’s mind was already formed.”

So he decides to put a good face on the matter and to humour Dora exactly the way she is. He does not seem to be enchanted by her playful ways any longer, though, but to have resigned himself to them:

”The old unhappy feeling pervaded my life. It was deepened, if it were changed at all; but it was as undefined as ever, and addressed me like a strain of sorrowful music faintly heard in the night. I loved my wife dearly, and I was happy; but the happiness I had vaguely anticipated, once, was not the happiness I enjoyed, and there was always something wanting. In fulfilment of the compact I have made with myself, to reflect my mind on this paper, I again examine it, closely, and bring its secrets to the light. What I missed, I still regarded—I always regarded—as something that had been a dream of my youthful fancy; that was incapable of realization; that I was now discovering to be so, with some natural pain, as all men did. But that it would have been better for me if my wife could have helped me more, and shared the many thoughts in which I had no partner; and that this might have been; I knew.

Between these two irreconcilable conclusions: the one, that what I felt was general and unavoidable; the other, that it was particular to me, and might have been different: I balanced curiously, with no distinct sense of their opposition to each other. When I thought of the airy dreams of youth that are incapable of realization, I thought of the better state preceding manhood that I had outgrown; and then the contented days with Agnes, in the dear old house, arose before me, like spectres of the dead, that might have some renewal in another world, but never more could be reanimated here.”

It’s also quite interesting that he mentions Agnes and her companionship in this context, and he even speculates on what his life would have been like if he had never met Dora. He remembers Annie’s words about the prerequisite of a happy marriage and his resigned conclusion is:

”It remained for me to adapt myself to Dora; to share with her what I could, and be happy; to bear on my own shoulders what I must, and be happy still. This was the discipline to which I tried to bring my heart, when I began to think. It made my second year much happier than my first; and, what was better still, made Dora's life all sunshine.”

However, there seems to be the shadow of death falling on the couple: Not only is Jip becoming rather long in the tooth, but also Dora is growing feebler after a miscarriage.

”I was not stunned by the praise which sounded in my ears, notwithstanding that I was keenly alive to it, and thought better of my own performance, I have little doubt, than anybody else did. It has always been in my observation of human nature, that a man who has any good reason to believe in himself never flourishes himself before the faces of other people in order that they may believe in him. For this reason, I retained my modesty in very self-respect; and the more praise I got, the more I tried to deserve.”

This seems like a man who is so much convinced of himself that he does not even deign to blow his own whistle, whereas he would not overstress his show of modesty. The narrator goes on like this:

”Having some foundation for believing, by this time, that nature and accident had made me an author, I pursued my vocation with confidence. Without such assurance I should certainly have left it alone, and bestowed my energy on some other endeavour. I should have tried to find out what nature and accident really had made me, and to be that, and nothing else.”

I find these words quite puzzling because to me they seem to imply that had David not met with (immediate?) success as a writer, he would have left off writing and turned to another field of action – and maybe this is even true of Dickens himself, who hit the public nerve with his first novel and who shaped the following novels closely to what he regarded as the public’s wishes – e.g. by introducing the America episodes into Martin Chuzzlewit when he noticed a waning interest in his novel. I have always thought that an author would feel in himself a calling regardless of what the public may think about his outpourings – which would, indeed, explain for but not excuse a lot of outpourings – and that in the worst case he would write for the drawer (as the German phrase goes), with a view to posterity. Here, however, David/Dickens seems to regard the calling – “nature” – as no more powerful an incentive to writing than “accident”, i.e. the reception of his novels by the public.

After these remarks on his successes as an author, David gives a humorous description of some further mishaps that befall their household, and after the plodding preceding chapter I welcomed the comic relief here even though I was appalled to learn that the page was going to be deported for stealing a gold watch, which shows how strict the law was at that time. David’s remonstrance that they must take a more serious outlook on housekeeping because it was not only themselves they were harming but also others by encouraging them to take illegal advantage of them – an interesting thought, by the way –, is met by poor Dora in her usual way, i.e. turning a matter-of-fact argument into an invective against herself – as if she had stolen the watch or told fibs – and so David tries to counter Dora’s childishness with increased seriousness and matter-of-factness. Even Shakespeare is used as a means of educating Dora, but to no avail. Finally it occurs to David, and this conclusion made me laugh out loud,

”that perhaps Dora’s mind was already formed.”

So he decides to put a good face on the matter and to humour Dora exactly the way she is. He does not seem to be enchanted by her playful ways any longer, though, but to have resigned himself to them:

”The old unhappy feeling pervaded my life. It was deepened, if it were changed at all; but it was as undefined as ever, and addressed me like a strain of sorrowful music faintly heard in the night. I loved my wife dearly, and I was happy; but the happiness I had vaguely anticipated, once, was not the happiness I enjoyed, and there was always something wanting. In fulfilment of the compact I have made with myself, to reflect my mind on this paper, I again examine it, closely, and bring its secrets to the light. What I missed, I still regarded—I always regarded—as something that had been a dream of my youthful fancy; that was incapable of realization; that I was now discovering to be so, with some natural pain, as all men did. But that it would have been better for me if my wife could have helped me more, and shared the many thoughts in which I had no partner; and that this might have been; I knew.

Between these two irreconcilable conclusions: the one, that what I felt was general and unavoidable; the other, that it was particular to me, and might have been different: I balanced curiously, with no distinct sense of their opposition to each other. When I thought of the airy dreams of youth that are incapable of realization, I thought of the better state preceding manhood that I had outgrown; and then the contented days with Agnes, in the dear old house, arose before me, like spectres of the dead, that might have some renewal in another world, but never more could be reanimated here.”

It’s also quite interesting that he mentions Agnes and her companionship in this context, and he even speculates on what his life would have been like if he had never met Dora. He remembers Annie’s words about the prerequisite of a happy marriage and his resigned conclusion is:

”It remained for me to adapt myself to Dora; to share with her what I could, and be happy; to bear on my own shoulders what I must, and be happy still. This was the discipline to which I tried to bring my heart, when I began to think. It made my second year much happier than my first; and, what was better still, made Dora's life all sunshine.”

However, there seems to be the shadow of death falling on the couple: Not only is Jip becoming rather long in the tooth, but also Dora is growing feebler after a miscarriage.

The following chapter, „I Am Involved in a Mystery“, brings back the Micawbers into focus and already hints at the end of one of the plot strands. David receives a lengthy letter from Mr. Micawber in which Micawber asks him for a meeting. At the same time, Mrs. Micawber writes to Traddles, asking him for help since her husband’s behaviour has changed for the worse. At that point I asked myself why David, on the receipt of a similar letter from Mrs. Micawber, has not reacted but David quickly solves this question by adding that at the time he received Mrs. Micawber’s letter he did not take it very seriously.

Mr. Micawber and David and Traddles finally meet, and during their mysterious conversation Micawber implies that he has found out about Uriah Heep’s villainous plots and that it will not be long before he is going to have enough proof to expose Uriah. At this point I was asking myself another question, which the narrator failed to answer: Why would a cunning, devious, secretive blackguard like Uriah Heep, a master-manipulator, make the mistake of letting any other person in on his business transactions? He must surely have anticipated the danger of such a person gathering information that he should better keep to himself. So – why would Uriah lower his guard to such an extent? And then to such a one as Mr. Micawber, whose reliability in business matters must have appeared very small to Uriah?

Mr. Micawber and David and Traddles finally meet, and during their mysterious conversation Micawber implies that he has found out about Uriah Heep’s villainous plots and that it will not be long before he is going to have enough proof to expose Uriah. At this point I was asking myself another question, which the narrator failed to answer: Why would a cunning, devious, secretive blackguard like Uriah Heep, a master-manipulator, make the mistake of letting any other person in on his business transactions? He must surely have anticipated the danger of such a person gathering information that he should better keep to himself. So – why would Uriah lower his guard to such an extent? And then to such a one as Mr. Micawber, whose reliability in business matters must have appeared very small to Uriah?

As the title of the chapter implies – „Mr. Peggotty’s Dream Comes True” –, Chapter 50, too, is one large step towards the resolution of some of the conflicts dealt with in the novel: Here, Martha finally helps re-unite Emily and her uncle. Emily has taken refuge in Martha’s humble abode, and Martha has secretly informed David and Mr. Peggotty about this state of affairs. David and Martha rush to Martha’s home, in order to find Miss Dartle in front of them on the staircase and enter into Martha’s room, where Emily has hidden. Miss Dartle has got her knowledge of Emily’s whereabouts through Littimer, and now her desire is to gloat upon the fallen woman and to torture her with her invectives as well as to put her under pressure by threatening Emily by saying that unless she goes back to where she came from, and where everyone knows her and her story, or openly lives in her quality as a fallen woman, Miss Dartle will mercilessly expose her to her neighbours.

David and Martha are listening to how Miss Dartle derides her female rival and how she transports herself into such a rage that she nearly attacks Emily, who breaks down before her, imploring her for sympathy and mercy. What I could not understand here is that David chose to listen and wait for Mr. Peggotty’s arrival on the scene rather than interfere and throw Miss Dartle out of the room. After all, this violent and passionate woman not only tortures Emily with words but there is also the danger of her getting physically rough. David says that he feels that Mr. Peggotty should be the first person to meet Emily, but there might also be his fear of setting Miss Dartle to carry out her threat if he throws her out of the house. Yet there is a lot of passivity in David, not only in this situation but also in another one: How can he bear the thought of leaving Agnes to the machinations of somebody like Uriah Heep for – is it months, is it years? – without putting a stop to the situation? To me, this passivity of David seems motivated more by the necessity for the plot to unroll than by David’s own feelings. How do you explain David’s non-action in these contexts?

Finally Mr. Peggotty’s footsteps are heard outside, and Miss Dartle hurriedly takes her leave. The chapter closes with Mr. Peggotty holding Emily in his arms – and with me thinking about the limitations of the first-person-narration.

David and Martha are listening to how Miss Dartle derides her female rival and how she transports herself into such a rage that she nearly attacks Emily, who breaks down before her, imploring her for sympathy and mercy. What I could not understand here is that David chose to listen and wait for Mr. Peggotty’s arrival on the scene rather than interfere and throw Miss Dartle out of the room. After all, this violent and passionate woman not only tortures Emily with words but there is also the danger of her getting physically rough. David says that he feels that Mr. Peggotty should be the first person to meet Emily, but there might also be his fear of setting Miss Dartle to carry out her threat if he throws her out of the house. Yet there is a lot of passivity in David, not only in this situation but also in another one: How can he bear the thought of leaving Agnes to the machinations of somebody like Uriah Heep for – is it months, is it years? – without putting a stop to the situation? To me, this passivity of David seems motivated more by the necessity for the plot to unroll than by David’s own feelings. How do you explain David’s non-action in these contexts?

Finally Mr. Peggotty’s footsteps are heard outside, and Miss Dartle hurriedly takes her leave. The chapter closes with Mr. Peggotty holding Emily in his arms – and with me thinking about the limitations of the first-person-narration.

Tristram wrote: "I felt tempted to just skim several passages and turn leaves over before I finished the page"

Tristram wrote: "I felt tempted to just skim several passages and turn leaves over before I finished the page"I feel tempted to skim every time I see Micawber has written a letter.

Tristram wrote: "Why would a cunning, devious, secretive blackguard like Uriah Heep, a master-manipulator, make the mistake of letting any other person in on his business transactions? He must surely have anticipated the danger of such a person gathering information that he should better keep to himself. So – why would Uriah lower his guard to such an extent? And then to such a one as Mr. Micawber, whose reliability in business matters must have appeared very small to Uriah?"

Tristram wrote: "Why would a cunning, devious, secretive blackguard like Uriah Heep, a master-manipulator, make the mistake of letting any other person in on his business transactions? He must surely have anticipated the danger of such a person gathering information that he should better keep to himself. So – why would Uriah lower his guard to such an extent? And then to such a one as Mr. Micawber, whose reliability in business matters must have appeared very small to Uriah?"Judging from how worried Micawber seems to be over the fate of his family, my thought was that Heep had blackmailed him in some fashion--that he can call down harm on Micawber and his family if M doesn't keep his mouth shut.

If this turns out to be true, and if Micawber braves the threats and reveals Heep's secrets anyway, then Heep has made a misjudgment of Micawber's character, thinking him worse than he is. Which I think is a thing that sometimes happens to depraved or dishonest people: they assume others are like themselves, and suffer because of it.

(Side note: I wish my autocorrect would stop trying to change Heep to Help.)

Tristram wrote: "To me, this passivity of David seems motivated more by the necessity for the plot to unroll than by David’s own feelings. How do you explain David’s non-action in these contexts?"

Tristram wrote: "To me, this passivity of David seems motivated more by the necessity for the plot to unroll than by David’s own feelings. How do you explain David’s non-action in these contexts?"I agree. This seems very plot-clunky in both cases you mention. It almost makes it worse that Dickens apparently understood this and so offers us a pretty ridiculous reason for David not to rush in on Emily--because her uncle ought to be the one to bring her back. Under the circumstances, who cares? Mr. Peggotty would not have countenanced this ongoing torture of the niece he loves--and also I have a higher opinion of Martha than to think she would be governed by the same motive, and she doesn't step forward either.

I was not looking forward to another Em'ly chapter but I perked up when I saw Miss Dartle popping in. But in the end I felt she was disappointing too. I think the explanation we've been working with here is that she was also in love with Steerforth and so she's violently jealous of Em'ly: but she was just so one-note unnuanced crazy in this chapter. I find myself comparing her to Edith Gombey who was also a distorted and maybe even deranged person whose interface with the world was pride and scorn, like Dartle--but Edith had more going on in her head than hate, and Dartle really doesn't. I'm not sure what she adds to the book, and I would be interested in hearing others' theories. Of course the story's not over yet, so maybe she has more to offer.

It might sound silly, but I feel like my interest in the story has been worn quite thin at this point. Things seem to be so stretched out. Yes, we now know Martha is depraved and still sees Em'ly as some kind of angel who happened to have fallen, but still angelic. Yes, we know Dora is a child-wife. Yayyy Em'ly is found, and Martha is, surprise, a hateful person who looks down on people. While there is enough going on in these chapters (like gazillions of foreshadowing that Dora will not grow old, Em'ly being found etc.) they felt like nothing happened. And while I thoroughly enjoy Dickens' writing style, I somehow have had trouble to get through for a couple of weeks now. Am I the only one? Anyway, I do remember now why DC is not my favourite Dickens novel.

I don't really have anything interesting to mention about this installment. I'm sorry. =S

I don't really have anything interesting to mention about this installment. I'm sorry. =S

Jantine wrote: "It might sound silly, but I feel like my interest in the story has been worn quite thin at this point. Things seem to be so stretched out. Yes, we now know Martha is depraved and still sees Em'ly a..."

Jantine wrote: "It might sound silly, but I feel like my interest in the story has been worn quite thin at this point. Things seem to be so stretched out. Yes, we now know Martha is depraved and still sees Em'ly a..."I feel the same way, Jantine. The first half of this novel is just magical. The second half...loose baggy monster, as Henry James said.

Yes, that's exactly it. Ah well, we're through half of the loose baggy monster already, so it'll be fine.

Tristram wrote: "How do you explain David’s non-action in these contexts?."

Tristram wrote: "How do you explain David’s non-action in these contexts?."On the hero-scale of 1-10 David has sunk down to a paltry 2.5 in my 'umble opinion.

I agree this was a pretty flat installment, and I am even more on-board now with just axing the Little Em'ly story altogether.

I agree this was a pretty flat installment, and I am even more on-board now with just axing the Little Em'ly story altogether. But I thought last week (before this) was fantastic, and I am still very curious to figure out how the Uriah Heep story plays out. I can't quite see how he's going to make trouble for Agnes, since she's made it clear to David that she won't marry Heep, and she and her father have friends who can take them in if worse comes to worst. But I am also not planning on underestimating Heep, or his umility. It will probably be something about the family honor, and I will be annoyed... but I have hopes I will be surprised and horrified.

(Now I want to call him Eep for being so umble.)

Overall my impression of this book so far is it's very uneven. Moments of brilliance and a lot that could have been left out altogether.

Also even though I can't quite bring myself to get excited about the re-appearance of her husband (meh, she'll figure it out, or Mr. Dick will), I still love Aunt Betsey.

Also even though I can't quite bring myself to get excited about the re-appearance of her husband (meh, she'll figure it out, or Mr. Dick will), I still love Aunt Betsey.

As several others, it seems, I was hardly interested in most of these chapters and especially how the scenes kept changing with each chapter. The only one I was interested in was the one to do with the Micawbers and Uriah Heep. I actually was waiting anxiously to see how Heep was going to be exposed in some way, then of course we moved on to another scene. I get very annoyed when that happens. I was bored by the chapter about Dora although I was wondering how this young woman is suddenly becoming so frail, and why no doctor is mentioned. I am very happy to see the ending of the book in sight. As someone mentioned, I did enjoy the beginning but lately I am ready for the book to end. I remember that this was not my favorite Dickens and now I remember why.

As several others, it seems, I was hardly interested in most of these chapters and especially how the scenes kept changing with each chapter. The only one I was interested in was the one to do with the Micawbers and Uriah Heep. I actually was waiting anxiously to see how Heep was going to be exposed in some way, then of course we moved on to another scene. I get very annoyed when that happens. I was bored by the chapter about Dora although I was wondering how this young woman is suddenly becoming so frail, and why no doctor is mentioned. I am very happy to see the ending of the book in sight. As someone mentioned, I did enjoy the beginning but lately I am ready for the book to end. I remember that this was not my favorite Dickens and now I remember why.

>>although I was wondering how this young woman is suddenly becoming so frail

>>although I was wondering how this young woman is suddenly becoming so frailI figured it was some kind of gynecological complication from her miscarriage, that nobody had any idea how to treat. Anecdotally I've heard of women never quite recovering after childbirth in this period, and I would guess a miscarriage could be equally if not more problematic.

Is anyone else disconcerted at how David's realization that he's married badly seems to coincide with his wife getting ill? I'm not suggesting he's poisoning her or anything, and women did get ill or die a lot from childbirth, and he keeps talking about how much he still loves her, but if she doesn't make it... how convenient. It's kind of uncomfortable.

Yes, that thought crossed my mind too. How convenient that he somehow seems to get the freedom to learn from his mistakes. And how sad (and annoying somehow) that Dora will have to pay with her life as the only option to not be made to live in an unhappy and unequal marriage for a long time or be degraded because she is spoiled goods.

It also makes me thankful that I now could divorce my husband if either of us would wish to go our separate ways (which we don't, because our marriage is based on equal minds as David puts it and we are doing great together), without it having to result in that kind of nastiness.

Julie, thanks for pointing something out in this installment that at least makes me happy with my own life ;-)

It also makes me thankful that I now could divorce my husband if either of us would wish to go our separate ways (which we don't, because our marriage is based on equal minds as David puts it and we are doing great together), without it having to result in that kind of nastiness.

Julie, thanks for pointing something out in this installment that at least makes me happy with my own life ;-)

Julie wrote: "Tristram wrote: "I felt tempted to just skim several passages and turn leaves over before I finished the page"

I feel tempted to skim every time I see Micawber has written a letter."

Yes, I can fully sympathize with you.

I feel tempted to skim every time I see Micawber has written a letter."

Yes, I can fully sympathize with you.

Julie wrote: "Tristram wrote: "Why would a cunning, devious, secretive blackguard like Uriah Heep, a master-manipulator, make the mistake of letting any other person in on his business transactions? He must sure..."

This may be Heep's weakness, i.e. the belief that everyone works the same way as he himself does. Manipulators are sometimes baffled when they find out that not everybody is sensitive to an appeal to their basest and most egoistic motives.

Good people come to grief in a similar way - by thinking that others will act as nobly as they would. It's ironic when you think of it.

This may be Heep's weakness, i.e. the belief that everyone works the same way as he himself does. Manipulators are sometimes baffled when they find out that not everybody is sensitive to an appeal to their basest and most egoistic motives.

Good people come to grief in a similar way - by thinking that others will act as nobly as they would. It's ironic when you think of it.

Julie wrote: "Tristram wrote: "To me, this passivity of David seems motivated more by the necessity for the plot to unroll than by David’s own feelings. How do you explain David’s non-action in these contexts?"

..."

Now that you mention Martha, I must say that I, too, find it very strange that she did not interfere on behalf of her friend. In fact, once she has led David to that place, she completely drops into the background, like some sort of mopey wallpaper, and we never hear of her again. I wonder whether she'll make another appearance in the book.

..."

Now that you mention Martha, I must say that I, too, find it very strange that she did not interfere on behalf of her friend. In fact, once she has led David to that place, she completely drops into the background, like some sort of mopey wallpaper, and we never hear of her again. I wonder whether she'll make another appearance in the book.

Jantine wrote: "It might sound silly, but I feel like my interest in the story has been worn quite thin at this point. Things seem to be so stretched out. Yes, we now know Martha is depraved and still sees Em'ly a..."

Coming to think of it, I'd say that all in all, David Copperfield is comparatively poor in plot, especially if you compare it to the novel that is going to follow but also to the earlier roller-coaster rides Dickens offered us. Maybe, here he is more interested in the different characters, and he does them really well. There is hardly any out-and-out villain here. You take Steerforth and Uriah and you will find that the narrator provides us with reasons why they are the way they are, something we never learn for Quilp or Ralph Nickleby.

Coming to think of it, I'd say that all in all, David Copperfield is comparatively poor in plot, especially if you compare it to the novel that is going to follow but also to the earlier roller-coaster rides Dickens offered us. Maybe, here he is more interested in the different characters, and he does them really well. There is hardly any out-and-out villain here. You take Steerforth and Uriah and you will find that the narrator provides us with reasons why they are the way they are, something we never learn for Quilp or Ralph Nickleby.

Ulysse wrote: "Tristram wrote: "How do you explain David’s non-action in these contexts?."

On the hero-scale of 1-10 David has sunk down to a paltry 2.5 in my 'umble opinion."

You are hardly too severe on Doady, Ulysse!

On the hero-scale of 1-10 David has sunk down to a paltry 2.5 in my 'umble opinion."

You are hardly too severe on Doady, Ulysse!

Julie wrote: ">>although I was wondering how this young woman is suddenly becoming so frail

I figured it was some kind of gynecological complication from her miscarriage, that nobody had any idea how to treat. ..."

Yes, Julie, that idea has also entered my mind. Dora's illness allows David to get out of his marriage with no self-reproach. That is kind of dishonest.

I figured it was some kind of gynecological complication from her miscarriage, that nobody had any idea how to treat. ..."

Yes, Julie, that idea has also entered my mind. Dora's illness allows David to get out of his marriage with no self-reproach. That is kind of dishonest.

Tristram wrote: "Ulysse wrote: "Tristram wrote: "How do you explain David’s non-action in these contexts?."

Tristram wrote: "Ulysse wrote: "Tristram wrote: "How do you explain David’s non-action in these contexts?."On the hero-scale of 1-10 David has sunk down to a paltry 2.5 in my 'umble opinion."

You are hardly too ..."

Well, there are still 150 pages left and it's impossible to be in the negatives on the hero-scale ;-)

Tristram wrote: "Maybe, here he is more interested in the different characters, and he does them really well. There is hardly any out-and-out villain here. You take Steerforth and Uriah and you will find that the narrator provides us with reasons why they are the way they are, something we never learn for Quilp or Ralph Nickleby."

True, he does do the characters really well. Now you mention the next book, he does great characters there too though, who all have the reasons why they became who and what they are just like Steerforth and Heep. I still cannot quite tell what puts me off in this installment, apart from indeed the lack of plot perhaps. I never saw myself as someone who needs to have a plot that badly though.

True, he does do the characters really well. Now you mention the next book, he does great characters there too though, who all have the reasons why they became who and what they are just like Steerforth and Heep. I still cannot quite tell what puts me off in this installment, apart from indeed the lack of plot perhaps. I never saw myself as someone who needs to have a plot that badly though.

Yes. These chapters do have a baggy feeling. Could it be as simple as Dickens beginning to run out of steam - and plot options - but still facing many instalments before the end of the novel? An editor’s pen would have helped, but the pace of producing the required length of each instalment must have been pressing as well. Who would dare edit Dickens anyway? :-)

And then we have Micawber. As a moderator I try to be reasonably neutral, and often stumble, but since his name has been mentioned...

Oh, he is so annoying. He is not funny and I’ve lost interest in his wife being so faithful. There seems to be an annoying character in every novel. I found Joey Bagstock horrid in D&S.

As for Little Em’ly I have space for sympathy. She is a flat character but I believe she is also a representative figure of many young women who were trapped in lives and fumbled out into a world where a person of a higher class, higher social standing, or a charming style first swept them off their feet and then swept them into the dustbin of social destruction. In a minor way Dickens and Burdett Coutts tried to reach some of these women. Their efforts met with moderate success. It is interesting to note that most the “graduates” of Urania Cottage emigrated to Australia. They did not remain in England.

There may be a few more moments of interest with Rosa still to come. Like Edith Dombey, I find Rosa to have more psychological interest and nuance than most Dickens characters, male or female.

Dickens has presented us with several prostitutes from Nancy in OT to Alice in D&S to Martha (and Em’ly?) in DC. Have we met a prostitute with a hard heart in any of his novels?

As for Dora and her waining health is it cruel to suggest Dickens has to remove her from the novel for reasons of the remaining plot? I wonder if Dickens had planned her failing health from her initial meeting with David or was it an afterthought?

And then we have Micawber. As a moderator I try to be reasonably neutral, and often stumble, but since his name has been mentioned...

Oh, he is so annoying. He is not funny and I’ve lost interest in his wife being so faithful. There seems to be an annoying character in every novel. I found Joey Bagstock horrid in D&S.

As for Little Em’ly I have space for sympathy. She is a flat character but I believe she is also a representative figure of many young women who were trapped in lives and fumbled out into a world where a person of a higher class, higher social standing, or a charming style first swept them off their feet and then swept them into the dustbin of social destruction. In a minor way Dickens and Burdett Coutts tried to reach some of these women. Their efforts met with moderate success. It is interesting to note that most the “graduates” of Urania Cottage emigrated to Australia. They did not remain in England.

There may be a few more moments of interest with Rosa still to come. Like Edith Dombey, I find Rosa to have more psychological interest and nuance than most Dickens characters, male or female.

Dickens has presented us with several prostitutes from Nancy in OT to Alice in D&S to Martha (and Em’ly?) in DC. Have we met a prostitute with a hard heart in any of his novels?

As for Dora and her waining health is it cruel to suggest Dickens has to remove her from the novel for reasons of the remaining plot? I wonder if Dickens had planned her failing health from her initial meeting with David or was it an afterthought?

Peter wrote: "Have we met a prostitute with a hard heart in any of his novels?"

Peter wrote: "Have we met a prostitute with a hard heart in any of his novels?"Maybe old Mrs. Brown in Dombey and Son, though I am not 100% sure she is a prostitute.

Bobbie wrote: "Can someone point out the chapter where Dora has a miscarriage? Somehow I missed that. Thanks."

Bobbie wrote: "Can someone point out the chapter where Dora has a miscarriage? Somehow I missed that. Thanks."It's super-indirect, in the chapter "Domestic":

I had hoped that lighter hands than mine would help to mould her character, and that a baby-smile upon her breast might change my child-wife to a woman. It was not to be. The spirit fluttered for a moment on the threshold of its little prison, and, unconscious of captivity, took wing.

Jantine wrote: "Tristram wrote: "Maybe, here he is more interested in the different characters, and he does them really well. There is hardly any out-and-out villain here. You take Steerforth and Uriah and you wil..."

Jantine wrote: "Tristram wrote: "Maybe, here he is more interested in the different characters, and he does them really well. There is hardly any out-and-out villain here. You take Steerforth and Uriah and you wil..."Yes. The characters are very compelling. I wonder if part of the issue is that the plot kind of underplays them--that for instance is why I was disappointed in how the story of the Strongs worked out: gorgeous character development to put them in positions where they could develop, and then they didn't really develop.

Julie wrote: "Bobbie wrote: "Can someone point out the chapter where Dora has a miscarriage? Somehow I missed that. Thanks."

Julie wrote: "Bobbie wrote: "Can someone point out the chapter where Dora has a miscarriage? Somehow I missed that. Thanks."It's super-indirect, in the chapter "Domestic":

I had hoped that lighter hands than m..."

Thanks Julie, I totally did not get that at all.

Julie wrote: "Peter wrote: "Have we met a prostitute with a hard heart in any of his novels?"

Maybe old Mrs. Brown in Dombey and Son, though I am not 100% sure she is a prostitute."

But then even Mrs. Brown is not completely hardened: Remember how she eventually does not cut off Florence's hair because she feels reminded of her daughter.

Maybe old Mrs. Brown in Dombey and Son, though I am not 100% sure she is a prostitute."

But then even Mrs. Brown is not completely hardened: Remember how she eventually does not cut off Florence's hair because she feels reminded of her daughter.

Bobbie wrote: "Julie wrote: "Bobbie wrote: "Can someone point out the chapter where Dora has a miscarriage? Somehow I missed that. Thanks."

It's super-indirect, in the chapter "Domestic":

I had hoped that lighte..."

At first, I wondered why Dickens did not make more of Dora's miscarriage in terms of dramatic tension but then it makes perfect sense because after all, it is David, the prospective father, who tells the story, and as such a memory must be extremely painful for him, he just touches on it in very indirect terms.

It's super-indirect, in the chapter "Domestic":

I had hoped that lighte..."

At first, I wondered why Dickens did not make more of Dora's miscarriage in terms of dramatic tension but then it makes perfect sense because after all, it is David, the prospective father, who tells the story, and as such a memory must be extremely painful for him, he just touches on it in very indirect terms.

I do wonder, as Peter mentions earlier, whether Dickens planned this storyline in advance as a way to move on from Dora. But I think that writing in installments meant in many cases that he probably did not plan too far in advance. Perhaps these questions would be answered if I went back and reread his biography.

I do wonder, as Peter mentions earlier, whether Dickens planned this storyline in advance as a way to move on from Dora. But I think that writing in installments meant in many cases that he probably did not plan too far in advance. Perhaps these questions would be answered if I went back and reread his biography.

Tristram wrote: "At first, I wondered why Dickens did not make more of Dora's miscarriage in terms of dramatic tension but then it makes perfect sense because after all, it is David, the prospective father, who tells the story, and as such a memory must be extremely painful for him, he just touches on it in very indirect terms."

Tristram wrote: "At first, I wondered why Dickens did not make more of Dora's miscarriage in terms of dramatic tension but then it makes perfect sense because after all, it is David, the prospective father, who tells the story, and as such a memory must be extremely painful for him, he just touches on it in very indirect terms."That makes a lot of sense but also Victorian novels avoid talking about pregnancy directly.

Tristram wrote: "Dear Curiosities,

Much of what I have read so far in this novel was well-paced and made the whole plot move on smoothly like However, I don’t know about you but for me Chapter 47 just dragged on a..."

Grump!!! Poor Martha, poor Dora, poor river. I think I got it all.

Much of what I have read so far in this novel was well-paced and made the whole plot move on smoothly like However, I don’t know about you but for me Chapter 47 just dragged on a..."

Grump!!! Poor Martha, poor Dora, poor river. I think I got it all.

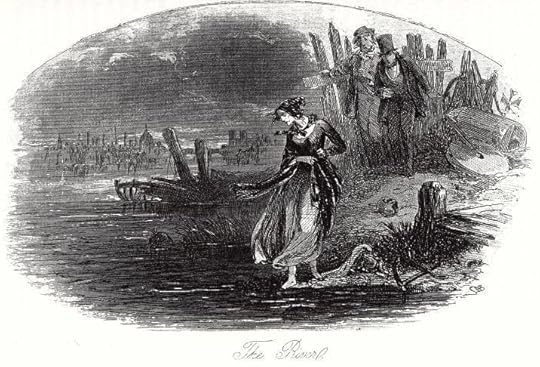

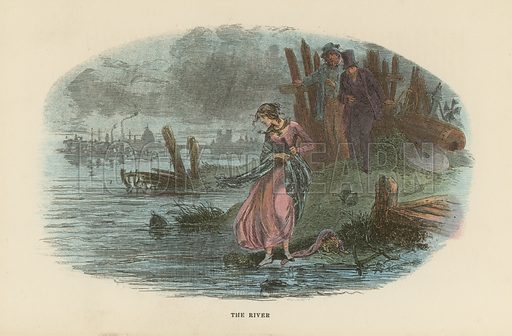

The River

Chapter 47

Phiz

working drawing

Commentary:

The sixteenth monthly number, which was issued in August 1850, comprises four chapters (chapters 47 through 50) rather than the usual three, although it was the customary thirty-two pages. For the first illustration, Phiz has chosen to realize the emotionally charged moment at which the despondent Martha, formerly a seamstress at Yarmouth, is about to drown herself at Millbank Pond on the Thames, the area's industrial wasteland forming a psychic backdrop for her attempted suicide which reprises Meggy Veck's attempted suicide in Trotty's dream vision at its culmination in The Chimes (1844), which likewise describes the plight of the Fallen Woman, the illustration depicts the following passage:

The neighbourhood was a dreary one at that time; as oppressive, sad, and solitary by night, as any about London. There were neither wharves nor houses on the melancholy waste of road near the great blank Prison. A sluggish ditch deposited its mud at the prison walls. Coarse grass and rank weeds straggled over all the marshy land in the vicinity. In one part, carcases of houses, inauspiciously begun and never finished, rotted away. In another, the ground was cumbered with rusty iron monsters of steam-boilers, wheels, cranks, pipes, furnaces, paddles, anchors, diving-bells, windmill-sails, and I know not what strange objects, accumulated by some speculator, and grovelling in the dust, underneath which—having sunk into the soil of their own weight in wet weather—they had the appearance of vainly trying to hide themselves. The clash and glare of sundry fiery Works upon the river-side, arose by night to disturb everything except the heavy and unbroken smoke that poured out of their chimneys. Slimy gaps and causeways, winding among old wooden piles, with a sickly substance clinging to the latter, like green hair, and the rags of last year’s handbills offering rewards for drowned men fluttering above high-water mark, led down through the ooze and slush to the ebb-tide. There was a story that one of the pits dug for the dead in the time of the Great Plague was hereabout; and a blighting influence seemed to have proceeded from it over the whole place. Or else it looked as if it had gradually decomposed into that nightmare condition, out of the overflowings of the polluted stream.

As if she were a part of the refuse it had cast out, and left to corruption and decay, the girl we had followed strayed down to the river’s brink, and stood in the midst of this night-picture, lonely and still, looking at the water.

There were some boats and barges astrand in the mud, and these enabled us to come within a few yards of her without being seen. I then signed to Mr. Peggotty to remain where he was, and emerged from their shade to speak to her. I did not approach her solitary figure without trembling; for this gloomy end to her determined walk, and the way in which she stood, almost within the cavernous shadow of the iron bridge, looking at the lights crookedly reflected in the strong tide, inspired a dread within me.

I think she was talking to herself. I am sure, although absorbed in gazing at the water, that her shawl was off her shoulders, and that she was muffling her hands in it, in an unsettled and bewildered way, more like the action of a sleep-walker than a waking person. I know, and never can forget, that there was that in her wild manner which gave me no assurance but that she would sink before my eyes, until I had her arm within my grasp.

At the same moment I said ‘Martha!’

She uttered a terrified scream, and struggled with me with such strength that I doubt if I could have held her alone. But a stronger hand than mine was laid upon her; and when she raised her frightened eyes and saw whose it was, she made but one more effort and dropped down between us. We carried her away from the water to where there were some dry stones, and there laid her down, crying and moaning. In a little while she sat among the stones, holding her wretched head with both her hands.

‘Oh, the river!’ she cried passionately. ‘Oh, the river!’

‘Hush, hush!’ said I. ‘Calm yourself.’

But she still repeated the same words, continually exclaiming, ‘Oh, the river!’ over and over again.

‘I know it’s like me!’ she exclaimed. ‘I know that I belong to it. I know that it’s the natural company of such as I am! It comes from country places, where there was once no harm in it—and it creeps through the dismal streets, defiled and miserable—and it goes away, like my life, to a great sea, that is always troubled—and I feel that I must go with it!’ I have never known what despair was, except in the tone of those words.

‘I can’t keep away from it. I can’t forget it. It haunts me day and night. It’s the only thing in all the world that I am fit for, or that’s fit for me. Oh, the dreadful river!’

To intensify the girl's loneliness in a city of a million souls, Phiz has placed that well-known London landmark, St. Paul's Cathedral, on the skyline behind the twin pylons and the rotting hulk that serves as a visual metaphor for her life. However, as Kitton notes, "the scene should have been reversed, and from this point of view (the river-side at Millbank) the dome of St. Paul's is not visible, although it is shown in the picture".

In etching the dark plate, Phiz may have failed to take into account that everything would be reversed in the printed illustration, so that the aerial perspective is in error. Indeed, the working drawing shows the scene reversed, with David and Mr. Peggotty entering the scene from the left rather than the right. However, in its symbolic and psychological value, the city on the horizon is a fitting detail, and, moreover, one which connects the previous scene, in which Steerforth's manservant, Lattimer, recounts for David the escape of Em'ly as dusk closes in upon the city in the distance.

Much more striking [than "The Wanderer"] is "The River" (ch. 46), the second dark plate Browne did for Dickens and the only one in David Copperfield (all forty of the etchings for Lever's Roland Cashel, overlapping in time of appearance with Copperfield, were produced by this method). Its uniqueness in this context is among several factors contributing to its success. It gives us the scene of a last-minute prevention of the standard watery fate of prostitutes, a fate which, the accompanying plate makes clear, could also have been Emily's. Phiz's conception of Martha at the river, and the technical differences between the two versions, seem to me more interesting than Dickens' hysterical narrative at this point. Phiz translates a strong and bold drawing in pen and wash into two carefully executed etchings which vary considerably in the handling of light and dark. Dickens rarely provided opportunities for sweeping, panoramic outdoor scenes, and when liberated from the confinement of interiors, narrow streets, or mild country views, Phiz seems to have indulged his propensity for dramatic landscape. (Ainsworth and Lever were to give him freer rein in this regard.)

As is often the case with dark plates, one steel is generally much darker than the other, and the lighter one depends more on subtle tonal variations in the mechanical tint, achieved by stopping-out, while the darker has a great deal more shading added by the etching needle, apparently over the tint. The effects are quite different, with the first steel subtler and smoother, and the second more strikingly dramatic in its contrasts and strong lines. In both versions the figure of Martha is given an unusual degree of solidity through the use of light and dark and the modeling of her features. Surrounding objects, bits of junk and flotsam, are subordinated to her predominantly bright figure, as are David and Mr. Peggotty. The hazy presence of St. Paul's in the background may suggest — as it does more emphatically in one of the dark plates to Bleak House — the distance of official religious institutions from such outcasts. Otherwise, Phiz has followed the text and made good use of the smoking factory chimneys specified by Dickens. [Steig 128-129]

The anti-Romantic, grimly social-realist vision of the Thames, with the Dore-like detritus of commercial shipping much in evidence, seems a fitting setting for the contemplation of suicide. Utilizing the potential of the bankside scene for pathetic fallacy, Phiz has carefully chosen background details to support the melancholy atmosphere established by the darkening sky and smoking chimneys in the distance: a stray buoy (centre), rotting pylons, a rat and anchor with chain attached (lower right, recalling the chain of marriage earlier in "Mrs. Gummidge casts a damp on our departure") and a rusting boiler taken straight out of Dickens's description of the nightmarish scene have a cumulative effect. Martha is in sharp relief, a gaunt figure of black and white against a grey background from which emerge David — identified by his respectable top hat, waistcoat, and coat — and Mr. Peggotty behind. Both men are startled as it dawns upon them that Martha has chosen "this gloomy end to her determined walk", rather than sought out some gloomy habitation. What Phiz does not show us, the metal-working fires, the barges and boats, and the shadow of the iron (i. e., Vauxhall) bridge, is as significant as what he has chosen to focus upon: a desperate, almost skeletal woman with "her shawl ... off her shoulders," staring down into the filthy water at her feet, about to make an end of herself as many a prostitute did in popular song and the popular press. In a moment, David, having tracked her to this dreary spot through Westminster, will recall her to herself, crying, "Martha!" and call her back from the brink of suicide in this lonely industrial wasteland anticipating T. S. Eliot's some seventy years later, a moral and emotional waste ground created by a bankrupt industrial system. But for the moment David cannot speak, for she is not yet within his grasp, and she remains an "unsettled and bewildered" somnambulist whose wild manner is confirmed by her passionately crying out, "Oh, the river! Oh, the river" repeatedly as she recognizes her kinship with that "polluted stream".

"Oh, the river!" she cried passionately. "Oh, the river!"

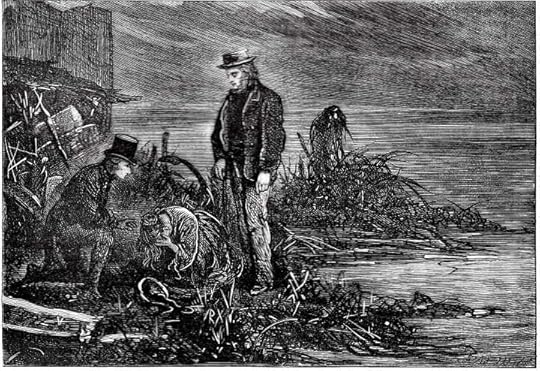

Chapter 47

Fred Barnard

1872 Household Edition

Commentary:

Dan'l peggotty and David Copperfield have arrived at the northern bank of the Thames just in time to prevent the former Yarmouth seamstress Martha Endell from committing suicide. Effective as Barnard's wood-engraving of the suicide interrupted may be, it is not as animated, dramatic, or moving as Phiz's August 1850 original, a dark steel-engraving entitled The River in Chapter 47, "Martha," in the sixteenth monthly number. Whereas the 1872 composite woodblock engraving has a generalized background and Dan'l Peggotty and David Copperfield have already rescued the Fallen Woman from drowning herself in the Thames, the original version juxtaposes the rescuers on the bank (right) with Martha Endell, windblown and staring into the black, disturbed waters, and the gloomy London skyline above images of dereliction and decay, sagging pylons and the skeleton of a boat, details which acquire psychological significance, while symbols of the Church (left of upper centre, St. Paul's Cathedral) and State (centre, The Tower of London) imply society's failure to address the social problem of The Fallen Woman that so absorbed Dickens during his time volunteering on the Urania Cottage project with the philanthropic banking heiress, the Baroness Angela Burdett Coutts (1814-1906). Through his friendship with Phiz and the anecdotes that the senior illustrator undoubtedly shared with him about illustrating David Copperfield, Barnard would have recognised the connection between Urania Cottage and the thwarted suicide of a prostitute in the 1849-50 novel.

Martha

Chapter 47

Sol Eytinge Jr.

1867 Diamond Edition

Commentary:

The fourteenth illustration — "Martha" — captures the moment in Chapter 47 when Martha stands on the brink of the Thames in Westminster: “I think she was talking to herself. I am sure, although absorbed in gazing at the water, that her shawl was off her shoulders, and that she was muffling her hands in it, in an unsettled and bewildered way, more like the action of a sleep-walker than a waking person. Eytinge's version of the character study of a would-be suicide, a woman driven to the extreme by social ostracism and economic privation, reflects Phiz's treatment of the same subject in "The River" , but Eytinge depicts nobody else in the scene, only of four single character studies in his sequence of sixteen studies, the others being the frontispiece of Little Em'ly as a child on the Yarmouth Denes, Steerforth sailing, and the ebullient Miss Mowcher.

The scene sketchily suggests the river water and a piece of detritus on the shore, but focuses the reader's attention on the skeletal, wind-swept figure and haggard visage of the woman lost morally and socially in the great metropolis. Were this a Phiz composition, we would almost certainly label it a "dark plate" since it conveys effectively the atmosphere of a night scene.

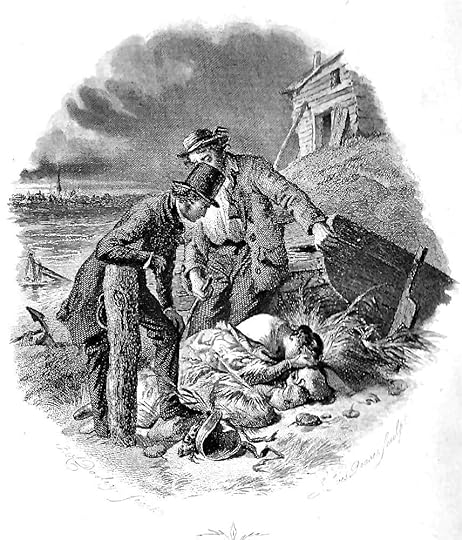

Saved from destruction

Chapter 47

Felix O. C. Darley

1863

Text Illustrated:

"I think [Martha] was talking to herself. I am sure, although absorbed in gazing at the water, that her shawl was off her shoulders, and that she was muffling her hands in it, in an unsettled and bewildered way, more like the action of a sleep-walker than a waking person. I know, and never can forget, that there was that in her wild manner which gave me no assurance but that she would sink before my eyes, until I had her arm within my grasp.

At the same moment I said "Martha!"

She uttered a terrified scream, and struggled with me with such strength that I doubt if I could have held her alone. But a stronger hand than mine was laid upon her; and when she raised her frightened eyes and saw whose it was, she made but one more effort and dropped down between us. We carried her away from the water to where there were some dry stones, and there laid her down, crying and moaning. In a little while she sat among the stones, holding her wretched head with both her hands.

"Oh, the river!" she cried passionately. "Oh, the river!"

"Hush, hush!" said I. "Calm yourself."

But she still repeated the same words, continually exclaiming, "Oh, the river!" over and over again.

"I know it's like me!" she exclaimed. "I know that I belong to it. I know that it's the natural company of such as I am! It comes from country places, where there was once no harm in it — and it creeps through the dismal streets, defiled and miserable — and it goes away, like my life, to a great sea, that is always troubled — and I feel that I must go with it!" I have never known what despair was, except in the tone of those words.

"I can't keep away from it. I can't forget it. It haunts me day and night. It's the only thing in all the world that I am fit for, or that's fit for me. Oh, the dreadful river!" [Chapter 47]

Commentary:

Darley might have chosen the title "Saved from Self-destruction"; certainly inventing such captions rather than choosing appropriate quotations is unusual among Darley's illustrations in the so-called "Household Edition" (1861-1871). In the parallel scene in the original serial, Phiz's The River for Chapter 47, "Martha" (August 1850), the background includes the dome of St. Paul's, whereas Darley includes only the spire of one of Sir Christopher Wren's city churches — possibly Southwark Cathedral rather than St. Magnus Martyr on the City side. On the other hand, Fred Barnard's version, "Oh, the river!" she cried passionately. "Oh, the river!" for the Household Edition includes no contextualizing landmarksexcept the decaying "old ferry-house" noted at the beginning of Chapter 47, although the illustrator has developed the weeds and sedge in the foreground to imply the unpleasant nature of the river shore at Westminster where Martha has attempted to commit suicide. For the first of two August 1850 illustrations, Phiz chose to realize the emotionally charged moment at which the despondent Martha, formerly a seamstress at Yarmouth, is about to drown herself at Millbank Pond on the Thames, the area's industrial wasteland forming a psychic backdrop for her attempted suicide which reprises Meggy Veck's attempted suicide in Trotty's dream vision at its culmination in The Chimes, Margaret and Her Child, which likewise describes the plight of the Fallen Woman. The channel marker (left) is not something that Dickens mentions, but the small objects on the sand in the foreground and the wooden boat (intended to stand for "boats and barges astrand in the mud")to the right are intended to create an appropriate sense of "corruption and decay" Darley gives no sense of the shadow of the iron bridge, "the lights crookedly reflected in the strong tide." However, the illustrator effectively employs the dark clouds to create an appropriately gloomy atmosphere. Here is melancholy investing all surrounding objects, but the illustration lacks the iron detritus of the industrial revolution, the "clash and glare of sundry fiery Works", the pall of chimney smoke, and the "ooze and slush of the ebb tide" through which Fred Barnard communicates a sense of Martha's despondency.

What distinguishes Darley's treatment is his blocking of the scene, foreground David and obscuring the reader's view of Dan'l Peggotty. The picture exemplifies a notion of charity as administered by members of the lower-middle and upper-middle classes, as the clothing of the Yarmouth sailor and the young urban professional suggest. Darley's Martha is not an ill-clad prostitute, but by her dress a woman of the middle classes who hides her face in shame. Although Darley undoubtedly consulted the illustrations in the original serial, for this 1863 volume he would not have had access to later mid-19th century programs of illustration such as those by Sol Eytinge, Jr. in TheDiamond Edition (1867) and Fred Barnard in the Household Edition, so that we may regard this frontispiece as a realistic re-working of the Phiz illustration for August 1850, with the low-lying Surrey shore and a single church spire substituted for the landmarks that Phiz moved from the northern to the southern shore of the Thames.

"When I can run about again, as I used to do, Aunt," said Dora, "I shall make Jip race. He is getting quite slow and lazy."

Chapter 48

Fred Barnard

1872 Household Edition

Text Illustrated:

But, as that year wore on, Dora was not strong. I had hoped that lighter hands than mine would help to mould her character, and that a baby-smile upon her breast might change my child-wife to a woman. It was not to be. The spirit fluttered for a moment on the threshold of its little prison, and, unconscious of captivity, took wing.

‘When I can run about again, as I used to do, aunt,’ said Dora, ‘I shall make Jip race. He is getting quite slow and lazy.’

‘I suspect, my dear,’ said my aunt quietly working by her side, ‘he has a worse disorder than that. Age, Dora.’

‘Do you think he is old?’ said Dora, astonished. ‘Oh, how strange it seems that Jip should be old!’

‘It’s a complaint we are all liable to, Little One, as we get on in life,’ said my aunt, cheerfully; ‘I don’t feel more free from it than I used to be, I assure you.’

‘But Jip,’ said Dora, looking at him with compassion, ‘even little Jip! Oh, poor fellow!’

‘I dare say he’ll last a long time yet, Blossom,’ said my aunt, patting Dora on the cheek, as she leaned out of her couch to look at Jip, who responded by standing on his hind legs, and baulking himself in various asthmatic attempts to scramble up by the head and shoulders. ‘He must have a piece of flannel in his house this winter, and I shouldn’t wonder if he came out quite fresh again, with the flowers in the spring. Bless the little dog!’ exclaimed my aunt, ‘if he had as many lives as a cat, and was on the point of losing ‘em all, he’d bark at me with his last breath, I believe!’

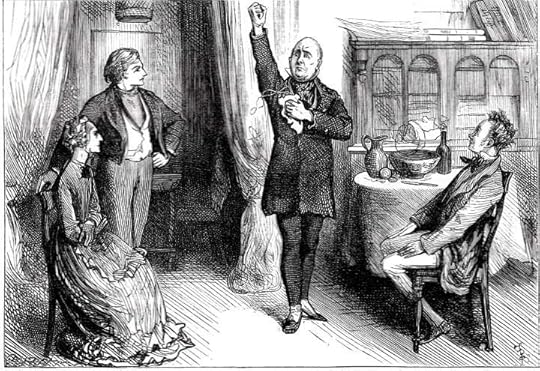

"And the name of the whole atrocious mass is - Heep!"

Chapter 49

Fred Barnard

1872 Household Edition

Text Illustrated:

‘My dear Copperfield,’ said Mr. Micawber, behind his handkerchief, ‘this is an occupation, of all others, requiring an untroubled mind, and self-respect. I cannot perform it. It is out of the question.’

‘Mr. Micawber,’ said I, ‘what is the matter? Pray speak out. You are among friends.’

‘Among friends, sir!’ repeated Mr. Micawber; and all he had reserved came breaking out of him. ‘Good heavens, it is principally because I AM among friends that my state of mind is what it is. What is the matter, gentlemen? What is NOT the matter? Villainy is the matter; baseness is the matter; deception, fraud, conspiracy, are the matter; and the name of the whole atrocious mass is—HEEP!’

My aunt clapped her hands, and we all started up as if we were possessed.

‘The struggle is over!’ said Mr. Micawber violently gesticulating with his pocket-handkerchief, and fairly striking out from time to time with both arms, as if he were swimming under superhuman difficulties. ‘I will lead this life no longer. I am a wretched being, cut off from everything that makes life tolerable. I have been under a Taboo in that infernal scoundrel’s service. Give me back my wife, give me back my family, substitute Micawber for the petty wretch who walks about in the boots at present on my feet, and call upon me to swallow a sword tomorrow, and I’ll do it. With an appetite!’

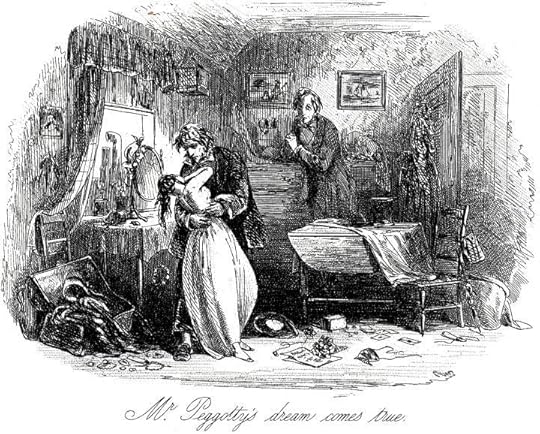

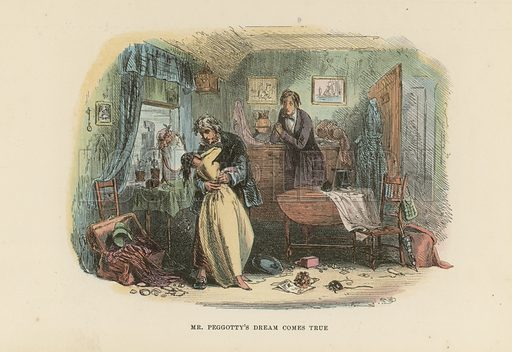

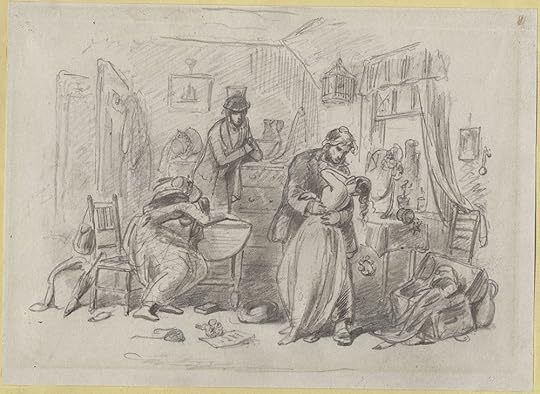

Mr. Peggotty's dream comes true

Chapter 50

Phiz

Commentary:

The second illustration for the sixteenth monthly number,issued in August 1850, complements the last of the four chapters (47 through 50) in this installment, the title of the plate being identical to the chapter title except for the latter's capitalisation of "Dream." For the first illustration, Phiz had chosen to realize Mr. Peggotty's and David's interrupting Martha as she contemplates committing suicide by drowning herself in the Thames. In this second August 1850 illustration, the two men again intervene, this time rescuing Emily from a life of degradation and an early death that was the inevitable fate of London prostitutes in the Hungry Forties. Just as Trotty Veck in The Chimes six years earlier had realized his most cherished hope, awakening from a nightmare marked by incendiarism, prostitution, and watery suicide to see his daughter "recalled to life," so here Mr. Peggotty at last reclaims his beloved niece after years of searching in vain. The picture resolves this strand of the plot while simultaneously delaying our apprehending Mr. Micawber's disclosure of the full extent of Uriah Heep's villainy, the illustration depicts the following passage:

I heard a distant foot upon the stairs. I knew it, I was certain. It was his, thank God!

She moved slowly from before the door when she said this, and passed out of my sight.

‘But mark!’ she added, slowly and sternly, opening the other door to go away, ‘I am resolved, for reasons that I have and hatreds that I entertain, to cast you out, unless you withdraw from my reach altogether, or drop your pretty mask. This is what I had to say; and what I say, I mean to do!’

The foot upon the stairs came nearer—nearer—passed her as she went down—rushed into the room!

‘Uncle!’

A fearful cry followed the word. I paused a moment, and looking in, saw him supporting her insensible figure in his arms. He gazed for a few seconds in the face; then stooped to kiss it—oh, how tenderly!—and drew a handkerchief before it.

"Mas'r Davy," he said, in a low tremulous voice, when it was covered, "I thank my Heav'nly Father as my dream's come true! I thank him hearty for having guided of me, in His own ways, to my darling!"

With these words he took her up in his arms; and, with the veiled face lying on his bosom, and addressed towards his own, carried her, motionless and unconscious, down the stairs.

Phiz has been unable in the illustration to convey the text's sense that Dan'l Peggotty regards himself as God's agent in Em'ly's reclamation. Rosa Dartle has repeatedly insulted and vilified Em'ly, and David has continually wished for her uncle's arrival: finally, he comes as Rosa departs. To intensify the exquisitely melodramatic moment, Phiz has turned the anguished girl's face away from the viewer (leaving the viewer to imagine her expression) as she twists in her uncle's embrace, as if trying to tear herself away in shame. Drawing our attention to the telling background details in this theatrical backdrop, Michael Steig in Dickens and Phiz comments upon a number of parallels between this iteration of the "fallen woman" (here, redeemed, and therefore clothed in white) and Phiz's exemplification of the same topos of the fallen or lost woman, in his illustration for chapter 22. Thus, through the poses and embedded details that are his hallmark Phiz reveals that he clearly understood that Em'ly is Martha's double, another reification of the social problem that so absorbed the philanthropical Dickens at this time as he worked with banking heiress Angela Burdett- Coutts to establish a training centre and refuge for reformed prostitutes at Shepherd's Bush, suburban London, which they appropriately dubbed "Urania Cottage" when they opened this charitable institution in 1847.

The rescue of Martha from the river is followed in the text by the rescue of Emily from prostitution, and so in the illustrations. "Mr. Peggotty's dream comes true" (ch. 50) was apparently a bit uncertain in the making, as the drawing (Elkins) suggests; in it not only does David wear a hat, but a female figure seated in the chair and slumped over the table is probably intended for Rosa Dartle, who has been haranguing Emily when the two men enter. The drawing (Elkins), which is reproduced in Kitton, Dickens and His Illustrators, fac. p. 84), is an awkward version, but it is understandable that Phiz should have included Rosa, since the text itself fails to indicate whether she managed an exit before the end of the chapter. Parallels to other plates are numerous. First, Emily recalls the main, kneeling figure of "Martha", whose face is similarly hidden. Then there are conventional allusions to Emily's lost innocence in the broken flowerpot, cracked mirror (into which she seems to be looking as her uncle holds her), and broken pitcher; Rosa's remark that Emily must "drop her pretty mask" — that is, be the prostitute that Rosa considers her, instead of the wronged woman she thinks herself — is rather awkwardly reflected in the domino mask and masked-ball program, since Emily surely has not come from a party, although perhaps these items are to be taken literally as the leavings of a previous, disreputable occupant.

From another point of view than Rosa's, however, the dropping of the mask might represent Emily's return from her pose as mistress of a grand gentleman to her real self, emblematized in the signs of her cherished past and happier future: the seashells that have fallen from her trunk, mementoes of her beloved home, the picture of a fisherman and a little girl, and that of a ship sailing on fair seas. This last may have its origin in the text's reference to "common pictures of ships on the walls," but recalling that in an earlier illustration Emily's fate has been foreshadowed by a picture of a ship in a storm, it is likely that the present one refers to her future, when she is happily reunited with her uncle. [Steig 128-129]

Whereas David and Mr. Peggotty are in the background in "The River," with the figure of Martha in sharp relief, here David, his hat resting on the disturbed tablecloth of the drop-leaf table (right), is up-centre, a distraught audience to the event unfolding before him in a disordered room that is the outward and visible sign of Em'ly's emotional distress, although in fact, as the text makes clear, this flat is being rented by Martha. The scene is a crescendo of emotion, of guilt, compassion, and forgiveness, occurring at the very end of the sixteenth instalment, signalling that in each monthly number from now on one strand of the plot will be brought to closure. Although published in early August, this scene was radically re-written at the end of July, giving the illustrator little time to make the necessary adjustments since Rosa Dartle was originally in the scene and David accompanied by Mr. Peggotty. As the scene now stands, Rosa has just departed and Mr. Peggotty has just arrived, with David as the first-person narrator hidden with Martha throughout.

Phiz has taken the detail of the pictures of sailing ships on the walls of Martha's room ("some common pictures of ships") from the text. Everything else in the room has come from the artist's imagination, except the chair, table, and open door. The room itself is located in the vicinity of Golden Square, between Regent and Great Windmill Streets, a decidedly "low" area not far from the Haymarket, where prostitutes in legions plied their trade after dark at that time. The room, therefore, should not be nearly so well furnished, let alone full of symbols such as the mask from a masked ball more fitting for Em'ly than Martha, especially if the mask implies Em'ly's having deceived Steerforth with an appearance of innocence rather than her having attended such an event with Steerforth in Italy. The chief disparity, however, is the absence of David's companion, Martha, and David's being in the room, rather than merely "looking in" from the little garret beyond.

"David's horrified yet compassionate expression as he watches Peggotty comfort his niece suggests he may at last have gone beyond mere sight to insight." (Cohen 107) He is no longer the passive observer looking about him in a detached manner as in "Our pew at church". David has emerged from the shadows in "The River" to engage himself mentally and emotionally with those whom he observes, reports upon, and analyses. He no longer re-enacts the role of the detached, clinical observer that Mr. Murdstone modelled for him all those years ago. Perhaps David's ghastly look, shocked expression, and the agitated hands betoken a recognition of the fate that Dan'l Peggotty's compassion have averted for his niece, whose tangled hair and curved body echo the posture of shame and self-loathing seen in Martha in "The River." However right Cohen may be in her analysis of the postures of the scene's figures, she is incorrect in identifying the contents of the room with elements from Em'ly's past exclusively:

In this scene, entitled with sad irony 'Mr. Peggotty's dream comes true,' Browne fills her shabby room with pictures alluding to her past — of small children, a fisherman, a ship — and objects alluding to her lost virginity: the broken ewer, cracked mirror, smashed flower pot, empty envelope, discarded dance program, single dancing slipper, and abandoned bonnet and purse like Martha's in the earlier scene.

The cherished "past" exemplified by these tokens is one which the Yarmouth seamstresses Em'ly and Martha share, a past rooted in small town, labouring class values, a sense of community, a close-knit family, from all of which society has excluded them because of their moral and sexual lapse. Thus, the objects in the room constitute Browne's special pleading for compassion for those who, after all, had worthy aspirations, joyful childhoods, and loving families. Em'ly in particular is somebody's child, somebody's sweetheart, somebody's childhood companion, rather than merely a ruined woman with a sordid past. The objects, then, plead against the viewer's accepting the moral judgment of Rosa Dartle, speaking from the judgment seat of upper-middle-class respectability.

The commentary from the Phiz drawing says this:

In etching the dark plate, Phiz may have failed to take into account that everything would be reversed in the printed illustration, so that the aerial perspective is in error. Indeed, the working drawing shows the scene reversed

I should know why the images were always reversed when printed, but I can't remember.

In etching the dark plate, Phiz may have failed to take into account that everything would be reversed in the printed illustration, so that the aerial perspective is in error. Indeed, the working drawing shows the scene reversed

I should know why the images were always reversed when printed, but I can't remember.

"Rosa Dartle sprang up from her seat; recoiled; and in recoiling struck at her"

Chapter 50

Fred Barnard

1872 Household Edition

Text Illustrated:

‘No! no!’ cried Emily, clasping her hands together. ‘When he first came into my way—that the day had never dawned upon me, and he had met me being carried to my grave!—I had been brought up as virtuous as you or any lady, and was going to be the wife of as good a man as you or any lady in the world can ever marry. If you live in his home and know him, you know, perhaps, what his power with a weak, vain girl might be. I don’t defend myself, but I know well, and he knows well, or he will know when he comes to die, and his mind is troubled with it, that he used all his power to deceive me, and that I believed him, trusted him, and loved him!’

Rosa Dartle sprang up from her seat; recoiled; and in recoiling struck at her, with a face of such malignity, so darkened and disfigured by passion, that I had almost thrown myself between them. The blow, which had no aim, fell upon the air. As she now stood panting, looking at her with the utmost detestation that she was capable of expressing, and trembling from head to foot with rage and scorn, I thought I had never seen such a sight, and never could see such another.

‘YOU love him? You?’ she cried, with her clenched hand, quivering as if it only wanted a weapon to stab the object of her wrath.

Emily had shrunk out of my view. There was no reply.

‘And tell that to ME,’ she added, ‘with your shameful lips? Why don’t they whip these creatures? If I could order it to be done, I would have this girl whipped to death.’

And so she would, I have no doubt. I would not have trusted her with the rack itself, while that furious look lasted. She slowly, very slowly, broke into a laugh, and pointed at Emily with her hand, as if she were a sight of shame for gods and men.

‘SHE love!’ she said. ‘THAT carrion! And he ever cared for her, she’d tell me. Ha, ha! The liars that these traders are!’

Julie wrote: "Tristram wrote: "At first, I wondered why Dickens did not make more of Dora's miscarriage in terms of dramatic tension but then it makes perfect sense because after all, it is David, the prospectiv..."

Julie

Yes indeed. It is very difficult to find pregnancy discussed in Victorian novels.

Julie

Yes indeed. It is very difficult to find pregnancy discussed in Victorian novels.

Kim wrote: "The commentary from the Phiz drawing says this:

In etching the dark plate, Phiz may have failed to take into account that everything would be reversed in the printed illustration, so that the aeri..."

Hi Kim

To have an image appear on a page in the 19C one first needed to have either a wood block or a steel plate that had a picture/image engraved or etched into the wood or steel.

Ink would then be applied to the engraved piece of wood or steel. Now, to get the image with the ink on it to transfer to another piece of paper you need to flip the steel/wood which has ink onto another piece of paper. Voila. The image will be reversed.

For fun ...