The Old Curiosity Club discussion

Little Dorrit

>

Little Dorrit Chapters 23-26

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

Chapter 24

The Evening of a Long Day

‘My only anxiety is,’ said Fanny, ‘that Mrs General should not get anything.’

‘She won’t get anything,’ said Mr Merdle.

The chapter begins with a discourse on the importance of Mr. Merdle. It is apparent that he is seen as a golden boy in England, a man with a Midas touch. This allows him the opportunity to mingle with the highest ranks of society in England. Merdle wants a Peerage or he said he wants to remain a plain person. It seems the only problem is that unlike the Barnacles or other ranked people, Merdle is a newcomer, but money speaks louder than blood in many ways.

This chapter begins three months after the passing of the Dorrit brothers. Fanny, now completely comfortable as Mrs Sparkler, has turned into a very arrogant and bossy diva. Her main focus in life is to cause the demolition of the Bosom. Mr Sparkler is both totally besotted by and ruled over by Fanny. The conversation between Sparkler and Fanny offers us some much sought for humour. I’m not sure how good an actress Fanny was in her earlier days but she certainly plays the part of the dominating wife to perfection. On the other hand, there is no light, spark, or flame from the ill-named Sparkler. Let’s face it. He is a total dud. We learn that Fanny sees herself as the new head of the family and in charge of taking care of her “little pet” sister Amy and the ailing Edward. I shutter at the thought of Fanny being the new head of the Dorrit family.

A knock comes to their door later in the evening and it turns out to be none other than Mr Merdle. This is strange, and so is Merdle’s behaviour. He seems adverse to having too much light around him and claims he was just out for a stroll. He is in dinner dress but says he has not been anywhere dining. Further strange behaviour includes pushing a chair around the room in front of himself (like a walker perhaps) and mentioning that “ I am as well as I usually am. I am well enough. I am as well as I want to be.” Strange phrases. At this point did you begin to get any feelings of unease?

When Fanny discusses her late father’s affairs Merdle seems distracted, but he is quite able to assure Fanny that Mrs General will not benefit from Mr Dorrit’s death. Merdle asks to borrow a penknife from the Sparkler's, but not one with a mother-of-pearl handle. It must have a dark handle. When offered a penknife with a tortoise-shell handle Merdle is satisfied and assures the Sparkler’s they will have it returned tomorrow. He promises that he will not ink it. The note in my edition of LD states that “pen-knives were at this time specifically for cutting pens.” The note continues “The tense irony of the passage is intricately sustained.” OK. Let’s see.

This short chapter comes to an end with Fanny, with tears of weariness in her eyes, looking out her window at the retreating “famous” Mr Merdle “going down the street, [appearing] to leap, and waltz, and gyrate, as if he were possessed of several Devils.”

A rather curious chapter. It begins with a short description of how famous Mr Merdle has become in England. Then we see into the married life of Fanny and Sparkler. There is little sparkle in this marriage. Finally, we join with Merdle as he visits the Sparkler’s. It is a rather awkward visit. Merdle seems ill at ease. What would he want a penknife for? Why a dark handle? Finally, what is meant by the image that Fanny has of Merdle leaping and gyrating. It is like he is trying to escape fro himself, to leave his own body. What devils inhabit his body? Soon we shall find out.

The Evening of a Long Day

‘My only anxiety is,’ said Fanny, ‘that Mrs General should not get anything.’

‘She won’t get anything,’ said Mr Merdle.

The chapter begins with a discourse on the importance of Mr. Merdle. It is apparent that he is seen as a golden boy in England, a man with a Midas touch. This allows him the opportunity to mingle with the highest ranks of society in England. Merdle wants a Peerage or he said he wants to remain a plain person. It seems the only problem is that unlike the Barnacles or other ranked people, Merdle is a newcomer, but money speaks louder than blood in many ways.

This chapter begins three months after the passing of the Dorrit brothers. Fanny, now completely comfortable as Mrs Sparkler, has turned into a very arrogant and bossy diva. Her main focus in life is to cause the demolition of the Bosom. Mr Sparkler is both totally besotted by and ruled over by Fanny. The conversation between Sparkler and Fanny offers us some much sought for humour. I’m not sure how good an actress Fanny was in her earlier days but she certainly plays the part of the dominating wife to perfection. On the other hand, there is no light, spark, or flame from the ill-named Sparkler. Let’s face it. He is a total dud. We learn that Fanny sees herself as the new head of the family and in charge of taking care of her “little pet” sister Amy and the ailing Edward. I shutter at the thought of Fanny being the new head of the Dorrit family.

A knock comes to their door later in the evening and it turns out to be none other than Mr Merdle. This is strange, and so is Merdle’s behaviour. He seems adverse to having too much light around him and claims he was just out for a stroll. He is in dinner dress but says he has not been anywhere dining. Further strange behaviour includes pushing a chair around the room in front of himself (like a walker perhaps) and mentioning that “ I am as well as I usually am. I am well enough. I am as well as I want to be.” Strange phrases. At this point did you begin to get any feelings of unease?

When Fanny discusses her late father’s affairs Merdle seems distracted, but he is quite able to assure Fanny that Mrs General will not benefit from Mr Dorrit’s death. Merdle asks to borrow a penknife from the Sparkler's, but not one with a mother-of-pearl handle. It must have a dark handle. When offered a penknife with a tortoise-shell handle Merdle is satisfied and assures the Sparkler’s they will have it returned tomorrow. He promises that he will not ink it. The note in my edition of LD states that “pen-knives were at this time specifically for cutting pens.” The note continues “The tense irony of the passage is intricately sustained.” OK. Let’s see.

This short chapter comes to an end with Fanny, with tears of weariness in her eyes, looking out her window at the retreating “famous” Mr Merdle “going down the street, [appearing] to leap, and waltz, and gyrate, as if he were possessed of several Devils.”

A rather curious chapter. It begins with a short description of how famous Mr Merdle has become in England. Then we see into the married life of Fanny and Sparkler. There is little sparkle in this marriage. Finally, we join with Merdle as he visits the Sparkler’s. It is a rather awkward visit. Merdle seems ill at ease. What would he want a penknife for? Why a dark handle? Finally, what is meant by the image that Fanny has of Merdle leaping and gyrating. It is like he is trying to escape fro himself, to leave his own body. What devils inhabit his body? Soon we shall find out.

Chapter 25

The Chief Butler Resigns the Seals of Office

“Sir, Mr. Merdle never was the gentleman, and no ungentlemanly act on Mr. Merdle’s part would surprise me. Is there anyone else I can send to you, or any other directions I can give before I leave, respecting what you would wish to be done?”

- The (former) Chief Butler

Our chapter begins with reference to a physician. It is notable that Dickens does not give this man a proper surname. We are told that he is a man of many secrets, of great knowledge, and great interest to those who know him. His knowledge was “as sharp as a razor; yet a razor is not a generally convenient instrument, and Physician’s plain bright scalpel, the far less keen, was adaptable to far wider purposes.“ In addition to Physician, there is a man known only as Bar, a lawyer who also is not given a proper surname. Why would Dickens not give these men a surname rather than just the name of an occupation?

There is a touch of flirtation between Mrs Merdle and Bar regarding the rumour that the Merdle’s are about to become titled, but Mrs Merdle does not give an answer. Evidently, Mr Merdle tells his wife nothing about his profession. The party that Mrs Merdle and Physician are attending is interrupted by a man who comes to the door with a note that he gives to Physician. Physician then gets his hat and follows the man to a public bath. Once at the baths the physician goes to a room and sees “the body of a heavily made man, with an obtuse head, and coarse, mean, common features.” Note the words “coarse,” “mean,” and “common features.” There is blood on the floor, a laudanum-bottle, and a tortoise-shell handled penknife on a ledge. The body of Mr Merdle is on the floor. His body, in death, has revealed his true character and true features. The devil that Fanny saw from her window has been released to the world in his death. Merdle has killed himself by taking a drug and then severing his jugular vein with the penknife. It is a ghastly death for a man of supposedly high stature and great respect. Mr Merdle’s life, his entire facade, has been a revealed.

There is little reaction about Merdle’s death from the Chief Butler. In fact, his only concern is to move on as quickly as possible. Rumours travel quickly that Merdle killed himself. More rumours begin to circulate that Merdle “Never had any money of his own, his ventures had been utterly reckless, and his expenditure had been most enormous.” The consequences of Merdle’s assumed wealth and now the truth that multitudes had been duped. He was a forger and a robber. He was the greatest forger and robber that had ever cheated the gallows.

Thoughts

This revelation is a shock to those who had placed their trust in Merdle and perhaps to the reader as well. Did you sense anything askew with Merdle and his enterprises while reading the earlier chapters? If so, what was it?

Anthony Trollope’s novel The Way We Live Today, written in 1875, has a similar plot. It is a very interesting novel. Some Curiosities may enjoy it. I certainly did.

The Chief Butler seems in quite a hurry to remove himself from the aftermath of Merdle’s suicide. He also said that Merdle was no gentleman. Do these actions possibly support Mr Dorrit’s belief that at one time the Chief Butler may have spent time years ago in the Marshalsea?

The Chief Butler Resigns the Seals of Office

“Sir, Mr. Merdle never was the gentleman, and no ungentlemanly act on Mr. Merdle’s part would surprise me. Is there anyone else I can send to you, or any other directions I can give before I leave, respecting what you would wish to be done?”

- The (former) Chief Butler

Our chapter begins with reference to a physician. It is notable that Dickens does not give this man a proper surname. We are told that he is a man of many secrets, of great knowledge, and great interest to those who know him. His knowledge was “as sharp as a razor; yet a razor is not a generally convenient instrument, and Physician’s plain bright scalpel, the far less keen, was adaptable to far wider purposes.“ In addition to Physician, there is a man known only as Bar, a lawyer who also is not given a proper surname. Why would Dickens not give these men a surname rather than just the name of an occupation?

There is a touch of flirtation between Mrs Merdle and Bar regarding the rumour that the Merdle’s are about to become titled, but Mrs Merdle does not give an answer. Evidently, Mr Merdle tells his wife nothing about his profession. The party that Mrs Merdle and Physician are attending is interrupted by a man who comes to the door with a note that he gives to Physician. Physician then gets his hat and follows the man to a public bath. Once at the baths the physician goes to a room and sees “the body of a heavily made man, with an obtuse head, and coarse, mean, common features.” Note the words “coarse,” “mean,” and “common features.” There is blood on the floor, a laudanum-bottle, and a tortoise-shell handled penknife on a ledge. The body of Mr Merdle is on the floor. His body, in death, has revealed his true character and true features. The devil that Fanny saw from her window has been released to the world in his death. Merdle has killed himself by taking a drug and then severing his jugular vein with the penknife. It is a ghastly death for a man of supposedly high stature and great respect. Mr Merdle’s life, his entire facade, has been a revealed.

There is little reaction about Merdle’s death from the Chief Butler. In fact, his only concern is to move on as quickly as possible. Rumours travel quickly that Merdle killed himself. More rumours begin to circulate that Merdle “Never had any money of his own, his ventures had been utterly reckless, and his expenditure had been most enormous.” The consequences of Merdle’s assumed wealth and now the truth that multitudes had been duped. He was a forger and a robber. He was the greatest forger and robber that had ever cheated the gallows.

Thoughts

This revelation is a shock to those who had placed their trust in Merdle and perhaps to the reader as well. Did you sense anything askew with Merdle and his enterprises while reading the earlier chapters? If so, what was it?

Anthony Trollope’s novel The Way We Live Today, written in 1875, has a similar plot. It is a very interesting novel. Some Curiosities may enjoy it. I certainly did.

The Chief Butler seems in quite a hurry to remove himself from the aftermath of Merdle’s suicide. He also said that Merdle was no gentleman. Do these actions possibly support Mr Dorrit’s belief that at one time the Chief Butler may have spent time years ago in the Marshalsea?

Chapter 26

Reaping the Whirlwind

“ Not being to bed, sir, since it began to get about. Being high and low, on the chance of finding some hope of saving any cinders from the fire. All in vain. All gone. All vanished.”

Pancks

Merdle’s inquest is over. The extent of his fraud is obvious. The bank is broken and Arthur’s Counting-house is ruined. Pancks rushes over to see Arthur and offer what help he can. Pancks tries to console Arthur but Arthur can only think of how he has ruined the honest and honourable Doyce. Arthur laments “ I have ruined him – brought him to shame and disgrace – ruined him, ruined him!” Pancks tries to take some of the blame on himself but is unsuccessful. Clennam sees only himself as the architect of the firm’s destruction. Everything is gone.

It is Arthur’s intent to do what he can to protect and preserve Doyce’s reputation and character as much as he can. Pancks suggests that Arthur seek legal help and so Mr Rugg is engaged as the company’s counsel. Rugg advises Arthur not to allow his feelings to get too much in the way of his thinking. Arthur rejects this suggestion. It is Arthur’s intent to declare that all actions were his actions. Arthur intends to address a letter to all the creditors and take full responsibility for the firm’s losses. Arthur does so and shower of responses follow. Rugg suggests that Arthur be taken on a writ from the Superior Courts rather than a small writ which would mean Arthur would end up in the Marshalsea prison. And so it unfolds. Arthur is taken to the Marshalsea where he is admitted by John Chivery Senior. John Junior escorts Arthur to the old room of Dorrit. Here Arthur realizes the associations “ with the one good and gentle creature who had sanctified it. Her absence in his altered fortunes made it, and made him in it, so very desolate and so much in need of such a face of love and truth, that he turned against the wall to weep, sobbing out, as his heart relieved itself, oh my Little Dorrit.”

Thoughts

What do we think of Clennam at this point in the novel? Does he remain the stuffy man who was blind to the affections of Amy? Is he now fully revealed as a truly upstanding man of honour who is willing to totally sacrifice his own future in order to preserve the honour and reputation of Doyce? Has it finally become obvious to Arthur as he begins his time in the Marshalsea how loving, caring, and steadfast Amy was to him and to her family? Has Clennam finally emerged as a surprise to you? On the other hand, do the most recent events in Clennam’s life further confirmed his character flaws you found in him earlier in the novel?

As we near the end of the novel I think it important we establish our position on his character.

There are still a few chapters left in the novel. What is your prediction as to how Dickens may conclude the novel?

Reaping the Whirlwind

“ Not being to bed, sir, since it began to get about. Being high and low, on the chance of finding some hope of saving any cinders from the fire. All in vain. All gone. All vanished.”

Pancks

Merdle’s inquest is over. The extent of his fraud is obvious. The bank is broken and Arthur’s Counting-house is ruined. Pancks rushes over to see Arthur and offer what help he can. Pancks tries to console Arthur but Arthur can only think of how he has ruined the honest and honourable Doyce. Arthur laments “ I have ruined him – brought him to shame and disgrace – ruined him, ruined him!” Pancks tries to take some of the blame on himself but is unsuccessful. Clennam sees only himself as the architect of the firm’s destruction. Everything is gone.

It is Arthur’s intent to do what he can to protect and preserve Doyce’s reputation and character as much as he can. Pancks suggests that Arthur seek legal help and so Mr Rugg is engaged as the company’s counsel. Rugg advises Arthur not to allow his feelings to get too much in the way of his thinking. Arthur rejects this suggestion. It is Arthur’s intent to declare that all actions were his actions. Arthur intends to address a letter to all the creditors and take full responsibility for the firm’s losses. Arthur does so and shower of responses follow. Rugg suggests that Arthur be taken on a writ from the Superior Courts rather than a small writ which would mean Arthur would end up in the Marshalsea prison. And so it unfolds. Arthur is taken to the Marshalsea where he is admitted by John Chivery Senior. John Junior escorts Arthur to the old room of Dorrit. Here Arthur realizes the associations “ with the one good and gentle creature who had sanctified it. Her absence in his altered fortunes made it, and made him in it, so very desolate and so much in need of such a face of love and truth, that he turned against the wall to weep, sobbing out, as his heart relieved itself, oh my Little Dorrit.”

Thoughts

What do we think of Clennam at this point in the novel? Does he remain the stuffy man who was blind to the affections of Amy? Is he now fully revealed as a truly upstanding man of honour who is willing to totally sacrifice his own future in order to preserve the honour and reputation of Doyce? Has it finally become obvious to Arthur as he begins his time in the Marshalsea how loving, caring, and steadfast Amy was to him and to her family? Has Clennam finally emerged as a surprise to you? On the other hand, do the most recent events in Clennam’s life further confirmed his character flaws you found in him earlier in the novel?

As we near the end of the novel I think it important we establish our position on his character.

There are still a few chapters left in the novel. What is your prediction as to how Dickens may conclude the novel?

I sometimes wonder if Bernie Madoff modeled himself after Mr. Merdle, right down to his (attempted) suicide.

I sometimes wonder if Bernie Madoff modeled himself after Mr. Merdle, right down to his (attempted) suicide.

Xan wrote: "I sometimes wonder if Bernie Madoff modeled himself after Mr. Merdle, right down to his (attempted) suicide."

Xan

Birds of a feather - fictional or not - may well flock together.

Xan

Birds of a feather - fictional or not - may well flock together.

I found humor in this week's segment, as well, but for me it came in chapter 25 with the description of the aftermath of Merdle's suicide. Our 21st century social media and 24 hour news cycle has nothing on the gossip of 19th century London. Then, as now, a few scanty facts are tossed together with a heaping helping of speculation and slant, and reported as gospel. Truth is secondary to scandal, and being the first to share it is much more important than accuracy.

I found humor in this week's segment, as well, but for me it came in chapter 25 with the description of the aftermath of Merdle's suicide. Our 21st century social media and 24 hour news cycle has nothing on the gossip of 19th century London. Then, as now, a few scanty facts are tossed together with a heaping helping of speculation and slant, and reported as gospel. Truth is secondary to scandal, and being the first to share it is much more important than accuracy.

Chapter 24 is well done. Plenty of foreshadowing, and interesting to read again, after knowing what comes next. For example, Merdle's assurances that Mrs. General will not benefit from Dorrit's death. Now we know that Fanny and her siblings won't, either.

Chapter 24 is well done. Plenty of foreshadowing, and interesting to read again, after knowing what comes next. For example, Merdle's assurances that Mrs. General will not benefit from Dorrit's death. Now we know that Fanny and her siblings won't, either. Our characters have been plunged into poverty. I understand Clennam trying to pay the company's debts from his own pockets, but surely other investors have not put all their eggs into Merdle's baskets, have they? Will this poverty be like the Dashwood ladies who downsized into a smaller, but still perfectly adequate house with servants? Or will everyone end up back at the Marshalsea, eating gruel?

Mary Lou wrote: "I found humor in this week's segment, as well, but for me it came in chapter 25 with the description of the aftermath of Merdle's suicide. Our 21st century social media and 24 hour news cycle has n..."

Mary Lou wrote: "I found humor in this week's segment, as well, but for me it came in chapter 25 with the description of the aftermath of Merdle's suicide. Our 21st century social media and 24 hour news cycle has n..."True. But we have added a twist. I'm sure no one in London said, "Well!!! If he's going to join the gossip club, then I'm moving to Paris."

Honestly, is there anyone here who didn't see this coming from the start of mr. Merdle's praises being sung? He was praised so much that it was clear from the start he was not as amazing and not doing as well as it seemed. We didn't know the extent of it, surely, but as has been mentioned during the last weeks: he wouldn't have been praised like an angel if he hadn't been the devil Dickens mentioned in chapter 24. And what a chapter it was, the foreshadowing was amazing.

In my mean moments I hope the Dorrits will be eating gruel in the Marshalsea for the rest of their lives. Especially Tip, Fanny, Sparkler and Mrs. Merdle. And as for Amy, it wouldn't be as bad for her. At least she'd be home, and she could still marry John, right?

In my mean moments I hope the Dorrits will be eating gruel in the Marshalsea for the rest of their lives. Especially Tip, Fanny, Sparkler and Mrs. Merdle. And as for Amy, it wouldn't be as bad for her. At least she'd be home, and she could still marry John, right?

Jantine wrote: "Honestly, is there anyone here who didn't see this coming from the start of mr. Merdle's praises being sung? He was praised so much that it was clear from the start he was not as amazing and not do..."

Jantine

Yes. There are times when Dickens telegraphs to us what will be coming many, many chapters before the curtain falls - or at times raises - on a character’s final fate.

The chapter was extremely well presented.

Believe it or not, I have never really thought about or speculated upon Mrs Merdle’s future, or lack of one. I have, however, always enjoyed the exit scene of the Chief Butler, a man destined no doubt to always land on his feet.

Jantine

Yes. There are times when Dickens telegraphs to us what will be coming many, many chapters before the curtain falls - or at times raises - on a character’s final fate.

The chapter was extremely well presented.

Believe it or not, I have never really thought about or speculated upon Mrs Merdle’s future, or lack of one. I have, however, always enjoyed the exit scene of the Chief Butler, a man destined no doubt to always land on his feet.

Yes, the butler knows on which side his bread is buttered! He obviously is more competent and grounded than Merdle or Dorrit ever were, and must have bristled at having to serve them. Their paranoia about his condescension was justified.

Yes, the butler knows on which side his bread is buttered! He obviously is more competent and grounded than Merdle or Dorrit ever were, and must have bristled at having to serve them. Their paranoia about his condescension was justified.

Yes, the Chief Butler wins the prize this week. Best lines. Best acting. Best - he is out of there. We don't really need an explanation. Good for him. On to the Dorrits and Authur. And prison. peace, janz

Yes, the Chief Butler wins the prize this week. Best lines. Best acting. Best - he is out of there. We don't really need an explanation. Good for him. On to the Dorrits and Authur. And prison. peace, janz

Flora's Tour of Inspection

Book II Chapter 23

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

"Affery was excusing herself with "Don't ask nothing of me, Arthur!" when Mr. Flintwinch stopped her with "Why not? Affery, what's the matter with you, woman? Why not, jade!" Thus expostulated with, she came unwillingly out of her corner, resigned the toasting-fork into one of her husband's hands, and took the candlestick he offered from the other.

"Go before, you fool!" said Jeremiah. "Are you going up, or down, Mrs. Finching?"

Flora answered, "Down."

"Then go before, and down, you Affery," said Jeremiah. "And do it properly, or I'll come rolling down the banisters, and tumbling over you!"

Affery headed the exploring party; Jeremiah closed it. He had no intention of leaving them. Clennam looking back, and seeing him following three stairs behind, in the coolest and most methodical manner exclaimed in a low voice, "Is there no getting rid of him!" Flora reassured his mind by replying promptly, "Why though not exactly proper Arthur and a thing I couldn't think of before a younger man or a stranger still I don't mind him if you so particularly wish it and provided you'll have the goodness not to take me too tight."

Wanting the heart to explain that this was not at all what he meant, Arthur extended his supporting arm round Flora's figure. "Oh my goodness me,' said she. "You are very obedient indeed really and it's extremely honourable and gentlemanly in you I am sure but still at the same time if you would like to be a little tighter than that I shouldn't consider it intruding."

In this preposterous attitude, unspeakably at variance with his anxious mind, Clennam descended to the basement of the house; finding that wherever it became darker than elsewhere, Flora became heavier, and that when the house was lightest she was too. Returning from the dismal kitchen regions, which were as dreary as they could be, Mistress Affery passed with the light into his father's old room, and then into the old dining-room; always passing on before like a phantom that was not to be overtaken, and neither turning nor answering when he whispered, "Affery! I want to speak to you!"

Commentary:

Although Little Dorrit does not appear in it, the picture offers a study of some of the novel's principal characters: at the top of the staircase, insulting his wife, Jeremiah Flintwinch, Mrs. Clennam's confidential servant (left); on the landing, the middle-aged, bourgeois couple, quondam sweethearts, Flora Finching and Arthur Clennam (centre); descending from the landing, candle in hand, Affery Flintwinch, Mrs. Clennam's highly anxious maid. The illustration also exemplifies what one might term "The Marriage Plot" of the novel. The illustration appeared as the tinted frontispiece of the Authentic Edition (1901). Certainly James Mahoney's dark wood-engraving of this same "tour" in the 1873 Household Edition leaves much to be desired when one compares it to Phiz's sharply delineated figures in his 1857 steel engraving.

- tinted frontispiece

Book II Chapter 23 - James Mahoney

"You can't be afraid of seeing anything in this darkness, Affery."

Book II Chapter 23

James Mahoney

Household Edition 1873

Text Illustrated:

"Affery headed the exploring party; Jeremiah closed it. He had no intention of leaving them. Clennam looking back, and seeing him following three stairs behind, in the coolest and most methodical manner exclaimed in a low voice, "Is there no getting rid of him!" Flora reassured his mind by replying promptly, "Why though not exactly proper Arthur and a thing I couldn't think of before a younger man or a stranger still I don't mind him if you so particularly wish it and provided you'll have the goodness not to take me too tight."

Wanting the heart to explain that this was not at all what he meant, Arthur extended his supporting arm round Flora's figure. "Oh my goodness me,' said she. "You are very obedient indeed really and it's extremely honourable and gentlemanly in you I am sure but still at the same time if you would like to be a little tighter than that I shouldn't consider it intruding."

In this preposterous attitude, unspeakably at variance with his anxious mind, Clennam descended to the basement of the house; finding that wherever it became darker than elsewhere, Flora became heavier, and that when the house was lightest she was too. Returning from the dismal kitchen regions, which were as dreary as they could be, Mistress Affery passed with the light into his father's old room, and then into the old dining-room; always passing on before like a phantom that was not to be overtaken, and neither turning nor answering when he whispered, "Affery! I want to speak to you!"

In the dining-room, a sentimental desire came over Flora to look into the dragon closet which had so often swallowed Arthur in the days of his boyhood — not improbably because, as a very dark closet, it was a likely place to be heavy in. Arthur, fast subsiding into despair, had opened it, when a knock was heard at the outer door.

Mistress Affery, with a suppressed cry, threw her apron over her head.

"What? You want another dose!' said Mr Flintwinch. 'You shall have it, my woman, you shall have a good one! Oh! You shall have a sneezer, you shall have a teaser!"

"In the meantime is anybody going to the door?" said Arthur.

"In the meantime, I am going to the door, sir," returned the old man so savagely, as to render it clear that in a choice of difficulties he felt he must go, though he would have preferred not to go. 'Stay here the while, all! Affery, my woman, move an inch, or speak a word in your foolishness, and I'll treble your dose!"

The moment he was gone, Arthur released Mrs Finching: with some difficulty, by reason of that lady misunderstanding his intentions, and making arrangements with a view to tightening instead of slackening.

"Affery, speak to me now!"

"Don't touch me, Arthur!" she cried, shrinking from him. "Don't come near me. He'll see you. Jeremiah will. Don't."

"He can't see me," returned Arthur, suiting the action to the word, "if I blow the candle out."

"He'll hear you," cried Affery.

"He can't hear me," returned Arthur, suiting the action to the words again, 'if I draw you into this black closet, and speak here.

Why do you hide your face?"

"Because I am afraid of seeing something."

"You can't be afraid of seeing anything in this darkness, Affery."

"Yes I am. Much more than if it was light."

"Why are you afraid?"

Because the house is full of mysteries and secrets; because it's full of whisperings and counseling's; because it's full of noises. There never was such a house for noises. I shall die of 'em, if Jeremiah don't strangle me first. As I expect he will."

Commentary:

The somewhat misogynistic comedy of the April 1857 Phiz steel-engraving Flora's Tour of Inspection deteriorates rapidly as Arthur blows out Affery's candle to allay her fears about her husband's overhearing their discussion. As in the text, the trio are in the dark — Affery doubly so, as terrified, she has thrown her apron over her face (as is her wont when confronting a stressful situation). Affery's apprehensions seem tantamount to paranoia here as she alludes the noises of the old house and the secrets that it harbors. One can hardly term this dark plate a study of the three characters — Affery, Arthur Clennam, and Flora Finching — since only Flora in her light dress is really discernible.

"You can't be afraid of seeing anything in this darkness, Affery."

Book II Chapter 23

James Mahoney

Household Edition 1873

Text Illustrated:

"Affery headed the exploring party; Jeremiah closed it. He had no intention of leaving them. Clennam looking back, and seeing him following three stairs behind, in the coolest and most methodical manner exclaimed in a low voice, "Is there no getting rid of him!" Flora reassured his mind by replying promptly, "Why though not exactly proper Arthur and a thing I couldn't think of before a younger man or a stranger still I don't mind him if you so particularly wish it and provided you'll have the goodness not to take me too tight."

Wanting the heart to explain that this was not at all what he meant, Arthur extended his supporting arm round Flora's figure. "Oh my goodness me,' said she. "You are very obedient indeed really and it's extremely honourable and gentlemanly in you I am sure but still at the same time if you would like to be a little tighter than that I shouldn't consider it intruding."

In this preposterous attitude, unspeakably at variance with his anxious mind, Clennam descended to the basement of the house; finding that wherever it became darker than elsewhere, Flora became heavier, and that when the house was lightest she was too. Returning from the dismal kitchen regions, which were as dreary as they could be, Mistress Affery passed with the light into his father's old room, and then into the old dining-room; always passing on before like a phantom that was not to be overtaken, and neither turning nor answering when he whispered, "Affery! I want to speak to you!"

In the dining-room, a sentimental desire came over Flora to look into the dragon closet which had so often swallowed Arthur in the days of his boyhood — not improbably because, as a very dark closet, it was a likely place to be heavy in. Arthur, fast subsiding into despair, had opened it, when a knock was heard at the outer door.

Mistress Affery, with a suppressed cry, threw her apron over her head.

"What? You want another dose!' said Mr Flintwinch. 'You shall have it, my woman, you shall have a good one! Oh! You shall have a sneezer, you shall have a teaser!"

"In the meantime is anybody going to the door?" said Arthur.

"In the meantime, I am going to the door, sir," returned the old man so savagely, as to render it clear that in a choice of difficulties he felt he must go, though he would have preferred not to go. 'Stay here the while, all! Affery, my woman, move an inch, or speak a word in your foolishness, and I'll treble your dose!"

The moment he was gone, Arthur released Mrs Finching: with some difficulty, by reason of that lady misunderstanding his intentions, and making arrangements with a view to tightening instead of slackening.

"Affery, speak to me now!"

"Don't touch me, Arthur!" she cried, shrinking from him. "Don't come near me. He'll see you. Jeremiah will. Don't."

"He can't see me," returned Arthur, suiting the action to the word, "if I blow the candle out."

"He'll hear you," cried Affery.

"He can't hear me," returned Arthur, suiting the action to the words again, 'if I draw you into this black closet, and speak here.

Why do you hide your face?"

"Because I am afraid of seeing something."

"You can't be afraid of seeing anything in this darkness, Affery."

"Yes I am. Much more than if it was light."

"Why are you afraid?"

Because the house is full of mysteries and secrets; because it's full of whisperings and counseling's; because it's full of noises. There never was such a house for noises. I shall die of 'em, if Jeremiah don't strangle me first. As I expect he will."

Commentary:

The somewhat misogynistic comedy of the April 1857 Phiz steel-engraving Flora's Tour of Inspection deteriorates rapidly as Arthur blows out Affery's candle to allay her fears about her husband's overhearing their discussion. As in the text, the trio are in the dark — Affery doubly so, as terrified, she has thrown her apron over her face (as is her wont when confronting a stressful situation). Affery's apprehensions seem tantamount to paranoia here as she alludes the noises of the old house and the secrets that it harbors. One can hardly term this dark plate a study of the three characters — Affery, Arthur Clennam, and Flora Finching — since only Flora in her light dress is really discernible.

Book II Chapter 24 - Phiz

Mr. Merdle a Borrower

Book II Chapter 24

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

"There was then a long silence; during which, Mrs. Sparkler, lying back on her sofa again, shut her eyes and raised her eyebrows in her former retirement from mundane affairs.

"But, however," said Mr. Merdle, "I am equally detaining you and myself. I thought I'd give you a call, you know."

"Charmed, I am sure," said Fanny.

"So I am off," added Mr. Merdle, getting up. "Could you lend me a penknife?"

It was an odd thing, Fanny smilingly observed, for her who could seldom prevail upon herself even to write a letter, to lend to a man of such vast business as Mr. Merdle.

"Isn't it?" Mr. Merdle acquiesced; "but I want one; and I know you have got several little wedding keepsakes about, with scissors and tweezers and such things in them. You shall have it back to-morrow."

"Edmund," said Mrs. Sparkler, "open (now, very carefully, I beg and beseech, for you are so very awkward) the mother of pearl box on my little table there, and give Mr. Merdle the mother of pearl penknife."

"Thank you," said Mr. Merdle; "but if you have got one with a darker handle, I think I should prefer one with a darker handle."

"Tortoise-shell?"

"Thank you," said Mr. Merdle; "yes. I think I should prefer tortoise-shell."

Edmund accordingly received instructions to open the tortoise-shell box, and give Mr. Merdle the tortoise-shell knife. On his doing so, his wife said to the master-spirit graciously: "I will forgive you, if you ink it."

"I'll undertake not to ink it," said Mr. Merdle.

The illustrious visitor then put out his coat-cuff, and for a moment entombed Mrs. Sparkler's hand: wrist, bracelet, and all. Where his own hand had shrunk to, was not made manifest, but it was as remote from Mrs. Sparkler's sense of touch as if he had been a highly meritorious Chelsea Veteran or Greenwich Pensioner."

Commentary:

Michael Steig in Dickens and Phiz regards the financier and banker Merdle, his name suggestive of the French for "excrement," as one of the book's "chief embodiments of evil", the other being the wife-murderer and would-be extortionist Rigaud-Blandois, who derive from very different literary traditions: whereas Rigaud is a melodramatic villain, with foreign accent, a nutcracker visage, and predatory intentions expressed in suave but excessive gesticulation, Merdle epitomizes Thomas Carlyle's cash nexus — it is as if he is a mere cipher, nothing in himself, and quite ill-at-ease with himself.

In the text, Merdle is a special kind of grotesque with largely symbolic qualities. He is always "taking himself into custody" (a hint of the criminal nature of his business); he is tyrannized over by the chief butler, suggesting his nouveau riche status as a financial manipulator who has risen to power almost overnight; and his relation to his wife is consistent with the limiting of his identity to the world of finance, for she is purchased as a "bosom" upon which to hang jewels. Even his name, suggesting merde, emblematically conveys the idea of a low, filthy substance, brought into unseemly contact with the highest of the land. Yet Dickens at the same time manages to evoke a degree of pity for Merdle as someone who is basically out of sympathy with the shallow society world in which he has risen so high, someone who doesn't know what to do with his success arid would be more comfortable as a private man. He is not a monster like such earlier characters who epitomize the cash-nexus values of Dickens' society — Pecksniff, Dombey, Heep, or Bounderby.

The Merdle subplot once again demonstrates the shakiness and instability of British society. The timing of the chapter is significant: three months after the deaths of the Dorrit brothers in Italy, and after the marriage of Fanny Dorrit to the obtuse Edmund Sparkler, son of Mrs. Merdle by her first marriage. Self-assured, convinced of her place in London's social hierarchy, Fanny is pregnant. She and her husband receive an unexpected visitor, the somewhat distracted banker, Mr. Merdle, who (oddly enough) asks to borrow a pen-knife without any explanation. Although Dickens's is a portrait of a man on the verge of ruin and suicide, Phiz's interpretation of the financier is unvarnished and totally lacking in caricature, although like Blandois he is a forger and swindler: "He was a reserved man, with a broad, overhanging, watchful head, . . . and a somewhat uneasy expression about his coat-cuffs, as if they were in his confidence, and reasons for being anxious to hide his hands" (I: 21, "Mr. Merdle's Complaint,"). Having previously done much for society but (supposedly) little for himself, he now takes decisive and overt action. Assuming the role of his own physician and psychiatrist, Merdle addresses his undiagnosed "complaint" by slitting his throat in a Turkish bath to escape the opprobrium of the failure of his house-of-cards financial empire in the succeeding chapter.

How much of his mental instability is evident in the intense gaze he directs towards his step-son as Edmund finds him an appropriate penknife from the box of writing materials? And has Phiz embedded emblems that comment upon his "complaint"? The original of Merdle was a financier named John Sadleir (1814-1856), Dickens's near contemporary and a member of Parliament whose multiple, fraudulent schemes collapsed in the insolvency of the Tipperary Bank early in 1856, as Dickens was beginning the novel. Is there anything in this substantial bourgeois (without Sadleir's mutton-chop whiskers) with kid gloves and silk hat that suggests the swindler who sat for the portrait? The Italian scenic painting and ornately framed mirror suggests Fanny's nouveau riche tendency to show off her affluence and sophistication in conspicuous display, and the hermetically-sealed clock merely suggests the lifestyle to which Fanny has aspired. However, the guttering candle between Merdle and Edmund Sparkler may imply his impending suicide. In the final analysis, Phiz's portraits of Merdle fall far short of Dickens's own in Book One, Chapter 21 and Book Two, Chapter 24. Sadlier's self-poisoning at Jack Straw's Castle, a Dickens haunt, on the night of 16 February 1856 hardly evoked popular sympathy, but Dickens allows the reader to penetrate the bland surface in "Mrs. Merdle's Complaint" (Book One, Chapter 33) to hear the plaintiff voice of a desperate husband:

"Pray don't be violent, Mr. Merdle," said Mrs. Merdle.

"Violent?" said Mr, Merdle. "You are enough to make me desperate. You don't know half of what I do to accommodate Society. You don't know anything of the sacrifices I make for it."

A benefactor of high society without being an ornament to society, Merdle sacrifices himself after his wife's stinging rebuke that he has no right to mix with it. Significantly, in the Household Edition volume of 1873 James Mahoney does not even bother to offer his own interpretation of that "dull red and yellow face", whereas Harry Furniss offers merely a desiccated, balding man in an oversized topcoat who will now take "the shortest way," a desperate man, a mere shell, who seems to have had the life-force sucked out of him.

Mr. Merdle a Borrower

Book II Chapter 24

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

"There was then a long silence; during which, Mrs. Sparkler, lying back on her sofa again, shut her eyes and raised her eyebrows in her former retirement from mundane affairs.

"But, however," said Mr. Merdle, "I am equally detaining you and myself. I thought I'd give you a call, you know."

"Charmed, I am sure," said Fanny.

"So I am off," added Mr. Merdle, getting up. "Could you lend me a penknife?"

It was an odd thing, Fanny smilingly observed, for her who could seldom prevail upon herself even to write a letter, to lend to a man of such vast business as Mr. Merdle.

"Isn't it?" Mr. Merdle acquiesced; "but I want one; and I know you have got several little wedding keepsakes about, with scissors and tweezers and such things in them. You shall have it back to-morrow."

"Edmund," said Mrs. Sparkler, "open (now, very carefully, I beg and beseech, for you are so very awkward) the mother of pearl box on my little table there, and give Mr. Merdle the mother of pearl penknife."

"Thank you," said Mr. Merdle; "but if you have got one with a darker handle, I think I should prefer one with a darker handle."

"Tortoise-shell?"

"Thank you," said Mr. Merdle; "yes. I think I should prefer tortoise-shell."

Edmund accordingly received instructions to open the tortoise-shell box, and give Mr. Merdle the tortoise-shell knife. On his doing so, his wife said to the master-spirit graciously: "I will forgive you, if you ink it."

"I'll undertake not to ink it," said Mr. Merdle.

The illustrious visitor then put out his coat-cuff, and for a moment entombed Mrs. Sparkler's hand: wrist, bracelet, and all. Where his own hand had shrunk to, was not made manifest, but it was as remote from Mrs. Sparkler's sense of touch as if he had been a highly meritorious Chelsea Veteran or Greenwich Pensioner."

Commentary:

Michael Steig in Dickens and Phiz regards the financier and banker Merdle, his name suggestive of the French for "excrement," as one of the book's "chief embodiments of evil", the other being the wife-murderer and would-be extortionist Rigaud-Blandois, who derive from very different literary traditions: whereas Rigaud is a melodramatic villain, with foreign accent, a nutcracker visage, and predatory intentions expressed in suave but excessive gesticulation, Merdle epitomizes Thomas Carlyle's cash nexus — it is as if he is a mere cipher, nothing in himself, and quite ill-at-ease with himself.

In the text, Merdle is a special kind of grotesque with largely symbolic qualities. He is always "taking himself into custody" (a hint of the criminal nature of his business); he is tyrannized over by the chief butler, suggesting his nouveau riche status as a financial manipulator who has risen to power almost overnight; and his relation to his wife is consistent with the limiting of his identity to the world of finance, for she is purchased as a "bosom" upon which to hang jewels. Even his name, suggesting merde, emblematically conveys the idea of a low, filthy substance, brought into unseemly contact with the highest of the land. Yet Dickens at the same time manages to evoke a degree of pity for Merdle as someone who is basically out of sympathy with the shallow society world in which he has risen so high, someone who doesn't know what to do with his success arid would be more comfortable as a private man. He is not a monster like such earlier characters who epitomize the cash-nexus values of Dickens' society — Pecksniff, Dombey, Heep, or Bounderby.

The Merdle subplot once again demonstrates the shakiness and instability of British society. The timing of the chapter is significant: three months after the deaths of the Dorrit brothers in Italy, and after the marriage of Fanny Dorrit to the obtuse Edmund Sparkler, son of Mrs. Merdle by her first marriage. Self-assured, convinced of her place in London's social hierarchy, Fanny is pregnant. She and her husband receive an unexpected visitor, the somewhat distracted banker, Mr. Merdle, who (oddly enough) asks to borrow a pen-knife without any explanation. Although Dickens's is a portrait of a man on the verge of ruin and suicide, Phiz's interpretation of the financier is unvarnished and totally lacking in caricature, although like Blandois he is a forger and swindler: "He was a reserved man, with a broad, overhanging, watchful head, . . . and a somewhat uneasy expression about his coat-cuffs, as if they were in his confidence, and reasons for being anxious to hide his hands" (I: 21, "Mr. Merdle's Complaint,"). Having previously done much for society but (supposedly) little for himself, he now takes decisive and overt action. Assuming the role of his own physician and psychiatrist, Merdle addresses his undiagnosed "complaint" by slitting his throat in a Turkish bath to escape the opprobrium of the failure of his house-of-cards financial empire in the succeeding chapter.

How much of his mental instability is evident in the intense gaze he directs towards his step-son as Edmund finds him an appropriate penknife from the box of writing materials? And has Phiz embedded emblems that comment upon his "complaint"? The original of Merdle was a financier named John Sadleir (1814-1856), Dickens's near contemporary and a member of Parliament whose multiple, fraudulent schemes collapsed in the insolvency of the Tipperary Bank early in 1856, as Dickens was beginning the novel. Is there anything in this substantial bourgeois (without Sadleir's mutton-chop whiskers) with kid gloves and silk hat that suggests the swindler who sat for the portrait? The Italian scenic painting and ornately framed mirror suggests Fanny's nouveau riche tendency to show off her affluence and sophistication in conspicuous display, and the hermetically-sealed clock merely suggests the lifestyle to which Fanny has aspired. However, the guttering candle between Merdle and Edmund Sparkler may imply his impending suicide. In the final analysis, Phiz's portraits of Merdle fall far short of Dickens's own in Book One, Chapter 21 and Book Two, Chapter 24. Sadlier's self-poisoning at Jack Straw's Castle, a Dickens haunt, on the night of 16 February 1856 hardly evoked popular sympathy, but Dickens allows the reader to penetrate the bland surface in "Mrs. Merdle's Complaint" (Book One, Chapter 33) to hear the plaintiff voice of a desperate husband:

"Pray don't be violent, Mr. Merdle," said Mrs. Merdle.

"Violent?" said Mr, Merdle. "You are enough to make me desperate. You don't know half of what I do to accommodate Society. You don't know anything of the sacrifices I make for it."

A benefactor of high society without being an ornament to society, Merdle sacrifices himself after his wife's stinging rebuke that he has no right to mix with it. Significantly, in the Household Edition volume of 1873 James Mahoney does not even bother to offer his own interpretation of that "dull red and yellow face", whereas Harry Furniss offers merely a desiccated, balding man in an oversized topcoat who will now take "the shortest way," a desperate man, a mere shell, who seems to have had the life-force sucked out of him.

Book II Chapter 24 - Harry Furniss

Mr. Merdle gives the Sparklers a call

Book II Chapter 24

Harry Furniss

Household Edition 1910

Text Illustrated:

"My only anxiety is," said Fanny,"that Mrs. General should not get anything."

"She won't get anything," said Mr. Merdle.

Fanny was delighted to hear him express the opinion. Mr. Merdle, after taking another gaze into the depths of his hat as if he thought he saw something at the bottom, rubbed his hair and slowly appended to his last remark the confirmatory words, "Oh dear no. No. Not she. Not likely."

As the topic seemed exhausted, and Mr Merdle too, Fanny inquired if he were going to take up Mrs. Merdle and the carriage in his way home?

"No," he answered; "I shall go by the shortest way, and leave Mrs. Merdle to —" here he looked all over the palms of both his hands as if he were telling his own fortune — "to take care of herself. I dare say she'll manage to do it."

"Probably," said Fanny.

There was then a long silence; during which, Mrs. Sparkler, lying back on her sofa again, shut her eyes and raised her eyebrows in her former retirement from mundane affairs.

"But, however," said Mr. Merdle, "I am equally detaining you and myself. I thought I'd give you a call, you know."

"Charmed, I am sure," said Fanny.

"So I am off," added Mr. Merdle, getting up. "Could you lend me a penknife?"

It was an odd thing, Fanny smilingly observed, for her who could seldom prevail upon herself even to write a letter, to lend to a man of such vast business as Mr. Merdle.

"Isn't it?" Mr. Merdle acquiesced; "but I want one; and I know you have got several little wedding keepsakes about, with scissors and tweezers and such things in them. You shall have it back to-morrow."

"Edmund," said Mrs. Sparkler, "open (now, very carefully, I beg and beseech, for you are so very awkward) the mother of pearl box on my little table there, and give Mr. Merdle the mother of pearl penknife."

"Thank you," said Mr. Merdle; "but if you have got one with a darker handle, I think I should prefer one with a darker handle."

"Tortoise-shell?"

"Thank you," said Mr. Merdle; "yes. I think I should prefer tortoise-shell."

Commentary:

The timing of the chapter is significant: three months after the deaths of the Dorrit brothers in Italy, and after the marriage of Fanny Dorrit to the obtuse Edmund Sparkler, son of Mrs. Merdle by her first marriage. Self-assured, convinced of her place in London's social hierarchy, and utterly indolent in the Furniss illustration, Fanny is pregnant — although the illustrator does not reinforce the text on this point. She and her husband receive an unexpected visitor, the somewhat distracted banker, Mr. Merdle, who (oddly enough) asks to borrow a pen-knife without any explanation. Although Dickens's is a portrait of a man on the verge of ruin and suicide, Phiz's interpretation of the financier is unvarnished and totally lacking in caricature, whereas Furniss depicts the failed "prop" of London high society as merely a desiccated, balding man in an oversized topcoat who will now take "the shortest way," a desperate man, a mere shell, who seems to have had the life-force sucked out of him.

Dickens's descriptions of Merdle are highly explicit, amounting to verbal portraiture: "He was a reserved man, with a broad, overhanging, watchful head, . . . and a somewhat uneasy expression about his coat-cuffs, as if they were in his confidence, and reasons for being anxious to hide his hands" ( "Mr. Merdle's Complaint"). But Furniss has chosen to depict Merdle as an aged wreck rather than a bourgeois in healthy middle-age. And in no respect does Furniss's version of Merdle physically resemble the nattily dressed, middle-aged financier named John Sadleir (1814-1856) upon whom Dickens based his portrait of a corrupt capitalist, but by 1910 the swindler's case had been long out of the popular mind.

Mr. Merdle gives the Sparklers a call

Book II Chapter 24

Harry Furniss

Household Edition 1910

Text Illustrated:

"My only anxiety is," said Fanny,"that Mrs. General should not get anything."

"She won't get anything," said Mr. Merdle.

Fanny was delighted to hear him express the opinion. Mr. Merdle, after taking another gaze into the depths of his hat as if he thought he saw something at the bottom, rubbed his hair and slowly appended to his last remark the confirmatory words, "Oh dear no. No. Not she. Not likely."

As the topic seemed exhausted, and Mr Merdle too, Fanny inquired if he were going to take up Mrs. Merdle and the carriage in his way home?

"No," he answered; "I shall go by the shortest way, and leave Mrs. Merdle to —" here he looked all over the palms of both his hands as if he were telling his own fortune — "to take care of herself. I dare say she'll manage to do it."

"Probably," said Fanny.

There was then a long silence; during which, Mrs. Sparkler, lying back on her sofa again, shut her eyes and raised her eyebrows in her former retirement from mundane affairs.

"But, however," said Mr. Merdle, "I am equally detaining you and myself. I thought I'd give you a call, you know."

"Charmed, I am sure," said Fanny.

"So I am off," added Mr. Merdle, getting up. "Could you lend me a penknife?"

It was an odd thing, Fanny smilingly observed, for her who could seldom prevail upon herself even to write a letter, to lend to a man of such vast business as Mr. Merdle.

"Isn't it?" Mr. Merdle acquiesced; "but I want one; and I know you have got several little wedding keepsakes about, with scissors and tweezers and such things in them. You shall have it back to-morrow."

"Edmund," said Mrs. Sparkler, "open (now, very carefully, I beg and beseech, for you are so very awkward) the mother of pearl box on my little table there, and give Mr. Merdle the mother of pearl penknife."

"Thank you," said Mr. Merdle; "but if you have got one with a darker handle, I think I should prefer one with a darker handle."

"Tortoise-shell?"

"Thank you," said Mr. Merdle; "yes. I think I should prefer tortoise-shell."

Commentary:

The timing of the chapter is significant: three months after the deaths of the Dorrit brothers in Italy, and after the marriage of Fanny Dorrit to the obtuse Edmund Sparkler, son of Mrs. Merdle by her first marriage. Self-assured, convinced of her place in London's social hierarchy, and utterly indolent in the Furniss illustration, Fanny is pregnant — although the illustrator does not reinforce the text on this point. She and her husband receive an unexpected visitor, the somewhat distracted banker, Mr. Merdle, who (oddly enough) asks to borrow a pen-knife without any explanation. Although Dickens's is a portrait of a man on the verge of ruin and suicide, Phiz's interpretation of the financier is unvarnished and totally lacking in caricature, whereas Furniss depicts the failed "prop" of London high society as merely a desiccated, balding man in an oversized topcoat who will now take "the shortest way," a desperate man, a mere shell, who seems to have had the life-force sucked out of him.

Dickens's descriptions of Merdle are highly explicit, amounting to verbal portraiture: "He was a reserved man, with a broad, overhanging, watchful head, . . . and a somewhat uneasy expression about his coat-cuffs, as if they were in his confidence, and reasons for being anxious to hide his hands" ( "Mr. Merdle's Complaint"). But Furniss has chosen to depict Merdle as an aged wreck rather than a bourgeois in healthy middle-age. And in no respect does Furniss's version of Merdle physically resemble the nattily dressed, middle-aged financier named John Sadleir (1814-1856) upon whom Dickens based his portrait of a corrupt capitalist, but by 1910 the swindler's case had been long out of the popular mind.

Book II Chapter 24 - James Mahoney

"He couldn't have a better nurse to bring him round," Mr. Sparkler made bold to opine. . . . "For a wonder I can agree with you," returned his wife, languidly turning her eyelids a little in his direction, "and can adopt your words"

Book II Chapter 24

James Mahoney

Household Edition 1873

Text Illustrated:

"Here Fanny stopped to weep, and to say, "Dear, dear, beloved papa! How truly gentlemanly he was! What a contrast to poor uncle!"

"From the effects of that trying time," she pursued, "my good little Mouse will have to be roused. Also, from the effects of this long attendance upon Edward in his illness; an attendance which is not yet over, which may even go on for some time longer, and which in the meanwhile unsettles us all by keeping poor dear papa's affairs from being wound up. Fortunately, however, the papers with his agents here being all sealed up and locked up, as he left them when he providentially came to England, the affairs are in that state of order that they can wait until my brother Edward recovers his health in Sicily, sufficiently to come over, and administer, or execute, or whatever it may be that will have to be done."

"He couldn't have a better nurse to bring him round," Mr. Sparkler made bold to opine.

"For a wonder, I can agree with you," returned his wife, languidly turning her eyelids a little in his direction (she held forth, in general, as if to the drawing-room furniture), "and can adopt your words. He couldn't have a better nurse to bring him round. There are times when my dear child is a little wearing to an active mind; but, as a nurse, she is Perfection. Best of Amys!"

Mr. Sparkler, growing rash on his late success, observed that Edward had had, biggodd, a long bout of it, my dear girl."

Commentary:

Three months after marriage, the Sparklers find that domesticity is anything but romantic on a hot summer evening in London as Fanny constantly criticizes and belittles Edmund for being more than a bit obtuse. Having married into society, Fanny expects to entertain society and to be invited to social affairs, despite the fact that she is pregnant and in mourning. She is determined to break free of her boring domesticity. Edmund is no conversationalist — but she knew his intellectual limitations before she married him, partly to take revenge for Mrs. Merdle's slighting her. Technically, of course, she is mourning for her father and uncle, but she seems to have little genuine emotion about their sudden deaths in Rome. Her pregnancy is yet another reason why they receive neither callers nor invitations. Edmund ventures to suggest that, once Tip has recovered from a bout of malaria and returned with Amy from Italy, Amy might keep her company. Fanny expresses skepticism about Amy's suitability as a companion in terms of participation in London society: "Darling little thing! Not, however, that Amy would do here alone". Here, Edmund Sparkler asserts that his sister-in-law, although an excellent nurse, would not be suitable in a social role — and his wife thoroughly concurs — apparently such concurrence being highly unusual in their daily conversations. In a moment, a knock at the door will interrupt these deliberations as the banker, Mr. Merdle, the couple's father-in-law, will pay a call and ominously ask to borrow a pen-knife.

Mahoney's illustration depicts Edmund as virtually unchanged, with his monocle still implying his limited intellectual capacity and high society background. On the other hand, Fanny is looking more and more like her mother-in-law, Mrs. Merdle, and less and less like the tall, slender dancer who watched her uncle practicing his clarinet in Book One, Chapter 20: They spoke no more, all the way back to the lodging where Fanny and her uncle lived. . . . A rather mournful Italian landscape in oils above Fanny sets a sombre mood for the conversation, and serves as a reminder of the deaths of William and Frederick Dorrit in Rome. Having matured suddenly into a respectable matron, Fanny finds the company of her husband as interesting as the houseplant beside which Mahoney has positioned him. The imperial posture of Mrs. Sparkler recalls a portrait of Mrs. Merdle in the original engravings by Phiz, Society Expresses its Views on a Question of Marriage (September 1856). In short, in taking on Edmund, Mahoney seems to be implying that she has replaced his mother as a controlling consciousness and severe judge.

"He couldn't have a better nurse to bring him round," Mr. Sparkler made bold to opine. . . . "For a wonder I can agree with you," returned his wife, languidly turning her eyelids a little in his direction, "and can adopt your words"

Book II Chapter 24

James Mahoney

Household Edition 1873

Text Illustrated:

"Here Fanny stopped to weep, and to say, "Dear, dear, beloved papa! How truly gentlemanly he was! What a contrast to poor uncle!"

"From the effects of that trying time," she pursued, "my good little Mouse will have to be roused. Also, from the effects of this long attendance upon Edward in his illness; an attendance which is not yet over, which may even go on for some time longer, and which in the meanwhile unsettles us all by keeping poor dear papa's affairs from being wound up. Fortunately, however, the papers with his agents here being all sealed up and locked up, as he left them when he providentially came to England, the affairs are in that state of order that they can wait until my brother Edward recovers his health in Sicily, sufficiently to come over, and administer, or execute, or whatever it may be that will have to be done."

"He couldn't have a better nurse to bring him round," Mr. Sparkler made bold to opine.

"For a wonder, I can agree with you," returned his wife, languidly turning her eyelids a little in his direction (she held forth, in general, as if to the drawing-room furniture), "and can adopt your words. He couldn't have a better nurse to bring him round. There are times when my dear child is a little wearing to an active mind; but, as a nurse, she is Perfection. Best of Amys!"

Mr. Sparkler, growing rash on his late success, observed that Edward had had, biggodd, a long bout of it, my dear girl."

Commentary:

Three months after marriage, the Sparklers find that domesticity is anything but romantic on a hot summer evening in London as Fanny constantly criticizes and belittles Edmund for being more than a bit obtuse. Having married into society, Fanny expects to entertain society and to be invited to social affairs, despite the fact that she is pregnant and in mourning. She is determined to break free of her boring domesticity. Edmund is no conversationalist — but she knew his intellectual limitations before she married him, partly to take revenge for Mrs. Merdle's slighting her. Technically, of course, she is mourning for her father and uncle, but she seems to have little genuine emotion about their sudden deaths in Rome. Her pregnancy is yet another reason why they receive neither callers nor invitations. Edmund ventures to suggest that, once Tip has recovered from a bout of malaria and returned with Amy from Italy, Amy might keep her company. Fanny expresses skepticism about Amy's suitability as a companion in terms of participation in London society: "Darling little thing! Not, however, that Amy would do here alone". Here, Edmund Sparkler asserts that his sister-in-law, although an excellent nurse, would not be suitable in a social role — and his wife thoroughly concurs — apparently such concurrence being highly unusual in their daily conversations. In a moment, a knock at the door will interrupt these deliberations as the banker, Mr. Merdle, the couple's father-in-law, will pay a call and ominously ask to borrow a pen-knife.

Mahoney's illustration depicts Edmund as virtually unchanged, with his monocle still implying his limited intellectual capacity and high society background. On the other hand, Fanny is looking more and more like her mother-in-law, Mrs. Merdle, and less and less like the tall, slender dancer who watched her uncle practicing his clarinet in Book One, Chapter 20: They spoke no more, all the way back to the lodging where Fanny and her uncle lived. . . . A rather mournful Italian landscape in oils above Fanny sets a sombre mood for the conversation, and serves as a reminder of the deaths of William and Frederick Dorrit in Rome. Having matured suddenly into a respectable matron, Fanny finds the company of her husband as interesting as the houseplant beside which Mahoney has positioned him. The imperial posture of Mrs. Sparkler recalls a portrait of Mrs. Merdle in the original engravings by Phiz, Society Expresses its Views on a Question of Marriage (September 1856). In short, in taking on Edmund, Mahoney seems to be implying that she has replaced his mother as a controlling consciousness and severe judge.

Having seen that Dickens based Merdle on a real person I looked him up:

John Sadleir (1813 – 17 February 1856) was an Irish financier and politician.

He entered the House of Commons of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland in 1847 as a Member of Parliament for Carlow. Sadleir co-founded the Catholic Defence Association in 1851 and was one of the leading figures in the Independent Irish Party which held the balance of power in the House of Commons when it formed in 1852.

He went on to hold minor office in Lord Aberdeen's coalition government from 1852 through 1854. He resigned his ministerial position in 1854 when he was found guilty of being implicated in a plot to imprison a depositor of the Tipperary Bank because the individual in question had refused to vote for him.

By February 1856 the Tipperary Bank was insolvent, owing to Sadleir's overdraft of £288,000. His own financial affairs were ruinous, and in his efforts to solve his problems he milked the London Bank, ruined a small Newcastle upon Tyne bank, sold forged shares of the Swedish Railway Company, raised money on forged deeds, and spent rents of properties he held in receivership and money entrusted to him as a solicitor. In this way he disposed of more than £1.5 million, mainly in disastrous speculations. Unable to face the consequences, he committed suicide near Jack Straw's Tavern on Hampstead Heath on February 17, 1856 by drinking prussic acid. The Times reported that "[t]he body of Mr J. Sadleir M.P. was found on Sunday morning, February 17 on Hampstead Heath, at a considerable distance from the public road. A large bottle labeled "Oil of Bitter Almonds" and a jug also containing the poison (prussic acid) lay by his side. "The body was identified by Edwin James QC MP and Thomas Wakley MP, editor of The Lancet. His brother James Sadleir, also an MP, was found to be deeply implicated in the fraud, having conspired with his younger brother. He was expelled from the House of Commons on February 16, 1857. He fled to the Continent, settling in Zurich and then Geneva. He was murdered there in 1881 while being robbed of his gold watch.

John Sadleir was buried in an unmarked grave in Highgate Cemetery."

Dickens isn't the only author who couldn't stay awake from John Sadleir, here are a few more:

An Old Score

W. S. Gilbert based part of his 1869 play An Old Score on the story of Sadleir's suicide.

An Old Score is an 1869 three-act comedy-drama written by English dramatist W. S. Gilbert based partly on his 1867 short story, Diamonds, and partly on episodes in the lives of William Dargan, an Irish engineer and railway contractor, and John Sadleir, a banker who committed suicide.

John Needham's Double

The 1885 novel (and later play and silent film) John Needham's Double by Joseph Hatton is also based on Sadleir.

The novel is subtitled "A Story Founded on Fact" and is based on the story of Irish financier and politician John Sadleir, who committed suicide.

The Way We Live Now

The central character of Anthony Trollope's The Way We Live Now (1875), Melmotte may have been based on Sadleir, as well.

Several real-life figures have been proposed as the inspiration for Augustus Melmotte: the French financier Charles Lefevre, as well as the Irish swindler John Sadlier.

An Old Score

W. S. Gilbert based part of his 1869 play An Old Score on the story of Sadleir's suicide.

An Old Score is an 1869 three-act comedy-drama written by English dramatist W. S. Gilbert based partly on his 1867 short story, Diamonds, and partly on episodes in the lives of William Dargan, an Irish engineer and railway contractor, and John Sadleir, a banker who committed suicide.

John Needham's Double

The 1885 novel (and later play and silent film) John Needham's Double by Joseph Hatton is also based on Sadleir.

The novel is subtitled "A Story Founded on Fact" and is based on the story of Irish financier and politician John Sadleir, who committed suicide.

The Way We Live Now

The central character of Anthony Trollope's The Way We Live Now (1875), Melmotte may have been based on Sadleir, as well.

Several real-life figures have been proposed as the inspiration for Augustus Melmotte: the French financier Charles Lefevre, as well as the Irish swindler John Sadlier.

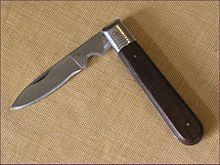

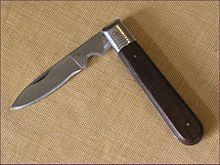

And as long as I'm looking things up:

Penknife, or pen knife, is a British English term for a small folding knife. Today the word penknife is the common British English term for both a pocketknife, which can have single or multiple blades, and for multi-tools, with additional tools incorporated into the design.

Originally, penknives were used for thinning and pointing quills (cf. penna, Latin for feather) to prepare them for use as dip pens and, later, for repairing or re-pointing the nib. A penknife might also be used to sharpen a pencil, prior to the invention of the pencil sharpener. In the mid-1800s, penknives were necessary to slice the uncut edges of newspapers and books.

A penknife did not necessarily have a folding blade, but might resemble a scalpel or chisel by having a short, fixed blade at the end of a long handle. One popular (but incorrect) folk etymology makes an association between the size of a penknife and that of a small ballpoint pen.

During the 20th century there has been a proliferation of multi-function knives with assorted blades and gadgets, including; awls, reamers, scissors, nail files, corkscrews, tweezers, toothpicks, and so on. The tradition continues with the incorporation of modern devices such as ballpoint pens, LED torches/flashlights, and USB flash drives.

The most famous example of a multi-function penknife is the Swiss Army knife, some versions of which number dozens of functions and are really more of a folding multi-tool, incorporating a blade or two, than a penknife with extras.

Penknife, or pen knife, is a British English term for a small folding knife. Today the word penknife is the common British English term for both a pocketknife, which can have single or multiple blades, and for multi-tools, with additional tools incorporated into the design.

Originally, penknives were used for thinning and pointing quills (cf. penna, Latin for feather) to prepare them for use as dip pens and, later, for repairing or re-pointing the nib. A penknife might also be used to sharpen a pencil, prior to the invention of the pencil sharpener. In the mid-1800s, penknives were necessary to slice the uncut edges of newspapers and books.

A penknife did not necessarily have a folding blade, but might resemble a scalpel or chisel by having a short, fixed blade at the end of a long handle. One popular (but incorrect) folk etymology makes an association between the size of a penknife and that of a small ballpoint pen.

During the 20th century there has been a proliferation of multi-function knives with assorted blades and gadgets, including; awls, reamers, scissors, nail files, corkscrews, tweezers, toothpicks, and so on. The tradition continues with the incorporation of modern devices such as ballpoint pens, LED torches/flashlights, and USB flash drives.

The most famous example of a multi-function penknife is the Swiss Army knife, some versions of which number dozens of functions and are really more of a folding multi-tool, incorporating a blade or two, than a penknife with extras.

Kim wrote: "

Flora's Tour of Inspection

Book II Chapter 23

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

"Affery was excusing herself with "Don't ask nothing of me, Arthur!" when Mr. Flintwinch stopped her with "Why not? Affery..."

Thanks Kim

Flora looks suitably comfortable in this Phiz illustration. Actually, let’s look at the four faces of the picture. The size of the Phiz illustrations are rather small but I have always been impressed with how much individualization Phiz managed to create in such a confined space. Each of the faces is unique. We can discern each character’s emotion. They are individual and unique even though very few strokes were used to create each etching.

I must say the tinting is not as horrid as the colourizations are.

What I did find curious was the way Browne rendered the staircase in the interior of the house. The house look very substantial, solid, and sturdy.

Flora's Tour of Inspection

Book II Chapter 23

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

"Affery was excusing herself with "Don't ask nothing of me, Arthur!" when Mr. Flintwinch stopped her with "Why not? Affery..."

Thanks Kim

Flora looks suitably comfortable in this Phiz illustration. Actually, let’s look at the four faces of the picture. The size of the Phiz illustrations are rather small but I have always been impressed with how much individualization Phiz managed to create in such a confined space. Each of the faces is unique. We can discern each character’s emotion. They are individual and unique even though very few strokes were used to create each etching.

I must say the tinting is not as horrid as the colourizations are.

What I did find curious was the way Browne rendered the staircase in the interior of the house. The house look very substantial, solid, and sturdy.

Kim wrote: "Book II Chapter 23 - James Mahoney

"You can't be afraid of seeing anything in this darkness, Affery."

Book II Chapter 23

James Mahoney

Household Edition 1873

Text Illustrated:

"Affery head..."

I find Mahoney’s rendition of the interior of the house much more faithful to the text than Browne’s. Fact is, there is little to see in this illustration and thus the solid tomb-like nature of Mrs Clennam’s residence is clearly suggested.